For most students, the nurse won’t see you now

As a school superintendent, Brian Keim expected to deal with standardized tests and union contracts. He didn’t count on insulin shots and untended broken bones.

For years, Laker Schools, a small, rural district in Huron County at the tip of Michigan’s thumb, didn’t have a school nurse, leaving untrained school secretaries to parcel out medication and give insulin shots between other tasks. Too many kids, Keim recalled, didn’t get medical care at all.

“There were some kids not getting proper health care, sometimes not even getting emergency care,” Keim said of students in his district, in which half of its nearly 900 students are considered economically disadvantaged. “There were some instances of broken bones that weren’t treated.”

That changed in 2012 when the district formed a partnership with Scheurer Hospital in Pigeon to place one of the hospital’s nurses in the 500-student combined middle and high school during morning hours.

Other Michigan students aren’t as lucky. About 800,000 kids across the state ‒ slightly more than half of all public school students - attend classes in buildings without a school nurse. Michigan has the third highest ratio of students to school nurses in the nation, according to a survey by the National Association of School Nurses. No one knows the exact figures because Michigan doesn’t track school nurses.

Michigan would need 1,757 more school nurses just to meet the federal recommended staffing level, according to a 2014 Michigan-based survey. That would take $88 million a year, at a conservative estimate of $50,000 per nurse.

Believing that funding help from Lansing is unlikely, some districts are holding out their hats to their communities, looking for support from hospitals, county health departments and foundations to get nurses back into school buildings.

“As a nurse, (the lack of school nurses) makes me scared for the safety of the kids,” said Rachel Vandenbrink, nurse coordinator at Grand Rapids Public Schools. “The number of kids with anaphylactic asthma is up. Diabetes Type 1 is up. The number of diabetics who need insulin at lunch time is up. These major chronic health conditions are being dealt with by staff without professional training, who really want to be there to teach.”

Michigan near the bottom

A 2008 survey found Michigan ranked 48th among the states in the ratio of students to school nurses, with 4,204 students per school nurse. Vermont had the lowest ratio, at 275 students per nurse. Closer to home, the ratio in Indiana was 1,022 students per nurse; Ohio, 2,377. The only states that had higher ratios were Utah, at 4,893 students per nurse, and Hawaii, which doesn’t have any school nurses.

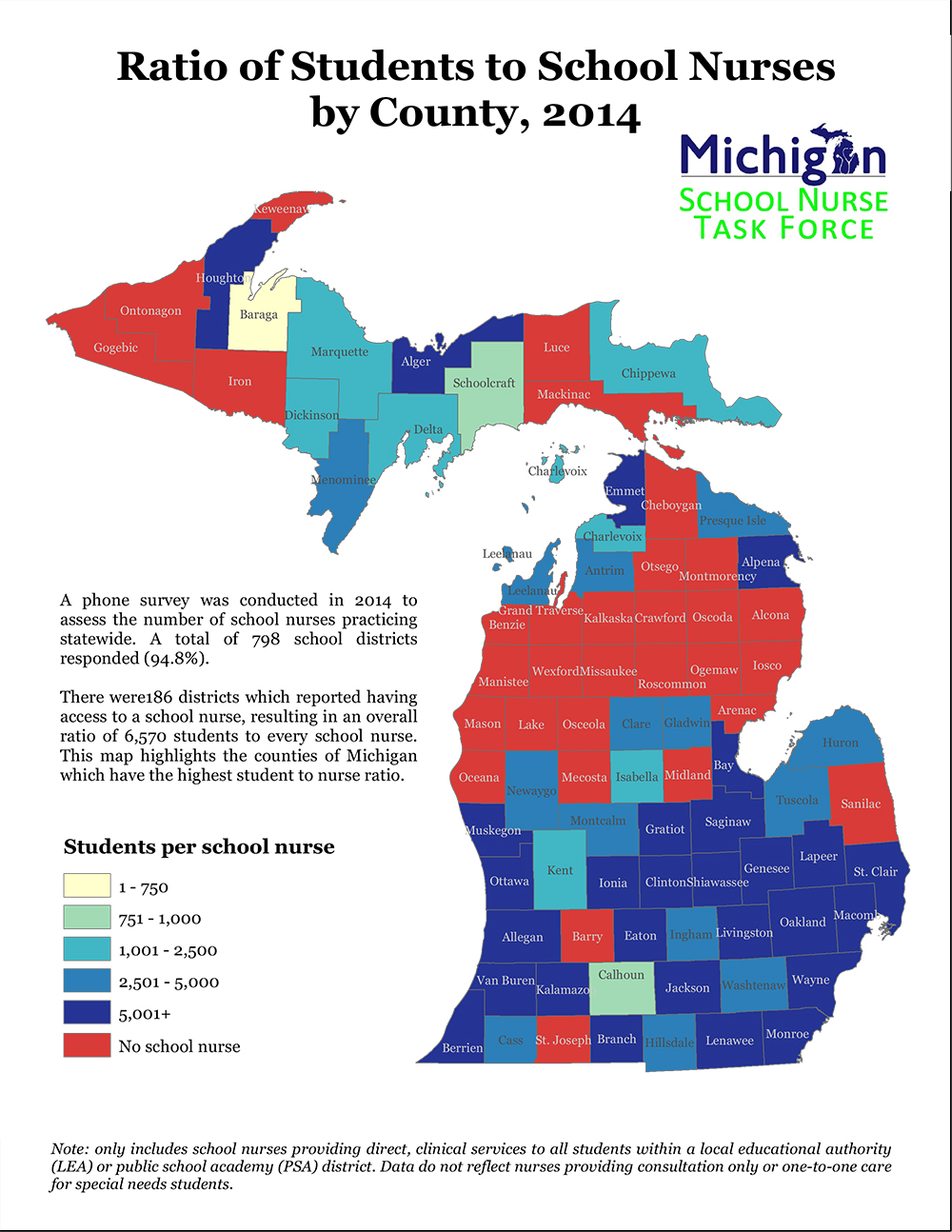

The shortage appears to be even more dire today, according to a report by the Michigan School Nurse Task Force, a committee formed by the Michigan Department of Education and Department of Health and Human Services to assess the issue.

In 2014, the task force called every traditional public school district and charter school in the state to ask if the district employed school nurses. The results:

- Only 28 percent of school districts had access to any type of school nursing services. Only 23 percent provided direct access a school nurse or other clinical service.

- About 46 percent of public school students (which include traditional public schools and charter schools) attended a district with nursing services, leaving 801,000 students without services.

- Overall, there was one full-time-equivalent nurse for every 6,570 students in the state. That’s eight times the ratio of one nurse per 750 students recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

School nurses do more than provide bandages for playground scrapes. Studies show that schools with nurses have lower absenteeism. School nurses help identify children with mental health issues and help manage chronic health issues. Kids with asthma missed fewer days of school and were hospitalized less when they attended schools with school nurses, according to one study.

“I can’t emphasize enough, a healthy learner is a better learner,” Laker Superintendent Keim said.

Like most states, Michigan has no statewide policy on school nurse staffing levels, said Linda Meeder, school nurse consultant for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. School districts and charter schools get per-pupil funding from the state, and individual districts make decisions on how to spend those funds. Some set aside money for nurses, others put every possible dollar into the classroom.

There were no school nurses in 31 Michigan counties in 2014, according to the survey by the Michigan School Nurse Task Force.

One of those counties was Barry County, south of Grand Rapids.

Cash-strapped districts, forced to make choices between classroom teachers and ancillary services like school nurses, always pick teachers, said Rich Franklin, superintendent of Barry Intermediate School District.

Without school nurses, “school secretaries are on the front lines of these things,” Franklin said, handing out prescription medication, measuring carbohydrates for diabetic children and giving insulin shots.

Franklin and Laker Superintendent Keim said they also worry about liability if a school employee not medically trained accidentally harms a student.

“By default, it’s the poor school secretary who never signed on for this,” Franklin said. “But I guess the kid needs his Ritalin, someone has to give it.”

The Barry ISD recently hired a nurse who works primarily with students with special needs, Franklin said. That nurse has been able to help train staff at county schools who have students with unusual health issues, such as a feeding tube or frequent seizures.

“Admittedly, it would be nice to have a school nurse” at individual schools, Franklin said, but the training now available for non-medical staff is better than the situation was in the Barry schools as recently as 2014.

Seeking help in communities

Laker Schools solved its nursing shortage by asking for help from neighboring Scheurer Hospital.

The district was able to provide an office for a nursing clinic after consolidating administrative staffs at the middle and high school.

“We thought we’d be seeing injuries from physical education class,” Keim said. “We were surprised by the severity of what we were seeing. We saw chronically neglected children, a diabetic child who hadn’t been properly diagnosed.”

The clinic had 3,600 contacts with students last school year, in a school of about 500 kids. “The kids were coming back more frequently than we expected,” Keim said. “We did not anticipate the extent of the need.”

“From the school’s perspective, they needed students who could perform at their best,” said Teresa Gascho, spokesperson for Scheurer Hospital. “We looked at it as an opportunity to promote wellness. We wanted to make sure students had a primary care provider. We did a lot of health education.”

In 2014, the hospital expanded its school nurse program to Caseville Public Schools. The service is free to the schools, but costs the hospital about $50,000 per school year per school district. That money is part of the hospital’s budget set aside for community service.

“It seems a little hokey, but it’s not just about taking care of sick people, but figuring out how to keep people well,” Gascho said.

Across the state, Munson Healthcare Charlevoix Hospital provides four nurses to nine school districts. In south central Michigan, Athens Area Schools partnered with the Calhoun County Health Department to provide a school nurse, supported through a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

The Athens nurse “has been a tremendous help educating families,” said Franklin, who previously was Athens superintendent.

Finding nontraditional funding sources for school nurses is one of the goals of the Michigan School Nurse Task Force. “We’re looking at funding partners, awareness and advocacy,” said state school nurse consultant Meeder. “Are we moving the dial? I think we’re beginning to.”

“There are so many obstacles to basic learning,” Keim said. “If we can get rid of those obstacles, I have a hunch we’d see a big difference.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Brooke McNabb, a nurse from Scheurer Health Systems meets with a student at Laker Junior-Senior High School. Like many small districts, Laker Schools doesn’t have money in its budget for a school nurse. But unlike other districts, the local hospital provides one. (Photo courtesy Scheurer Health Systems)

Brooke McNabb, a nurse from Scheurer Health Systems meets with a student at Laker Junior-Senior High School. Like many small districts, Laker Schools doesn’t have money in its budget for a school nurse. But unlike other districts, the local hospital provides one. (Photo courtesy Scheurer Health Systems)