Twenty years after NAFTA, a mini Detroit rises in Mexico

SALTILLO, Mexico - On a hilltop along the edge of this northeast Mexican city, row upon row of tiny stucco homes are sprouting. They are being erected on orders of the federal government, which envisions an influx of families from distant pueblos looking for salvation in the booming automotive industry. Driving into town, workers are greeted by a gargantuan, American-style mall with a Walmart, Nine West and a Liverpool department store that invites customers to shop now and pay later, a rather new concept in this country.

To the north, in Ramos Arizpe, the Universidad Tecnologica de Coahuila is training the next generation of skilled auto workers as plant technicians and engineers for Big Three companies like General Motors and Chrysler, or suppliers like Magna International, which have sprawling plants in the region. They are learning English, and even French, in hopes that they will someday work side-by-side with their automotive counterparts in Detroit or perhaps Canada.

Twenty years after passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement, known as NAFTA, the auto industry’s rising presence in Mexico has helped bring many of the totems of middle class life to growing manufacturing cities like Saltillo, which are now often described as little Detroits, for better or worse.

Inside the state-run university labs, students use equipment donated by the plants operated by U.S. automakers, who are betting these students will one day work for them. Students like Ernesto Gonzalez, 22, of Saltillo, who said he is about to start an internship with Magna.

“I thought that electronics and mechanics are the kind of things are going to help me in the future here in Saltillo,” said Gonzalez as he and his classmates constructed a Tesla coil, a practical exercise that he said would teach them wireless technology. “The auto industry is very important here. I think Saltillo and Ramos are places that are completely dedicated to the auto industry.”

Since NAFTA’s passage, vehicle production in Mexico has tripled, from 1.1 million in 1994 to a projected 3.2 million vehicles this year. Increased exports mean the industry now accounts for more than 20 percent of foreign receipts. Mexico’s auto growth is not just from NAFTA, far from it. Mexico now has trade agreements with more than 40 countries, with European and Asian manufacturers building auto plants across Mexico.

Autos booming

Mexico’s rising auto fortunes were solidified earlier this year when its production surpassed that of Latin American rival Brazil. Auto industry analysts predict the trend to continue after manufacturers like BMW announced plans to invest $1 billion in a plant in the central Mexican city of San Luis Potosi that will build 150,000 new vehicles a year starting in 2019. The German automaker follows Honda and Mazda, both of which opened plants in the south central Mexican state of Guanajuato earlier this year.

“The auto industry in Mexico is just booming, it's taking off right now and it´s probably the industry in which Mexico is the most competitive,” said Christopher Wilson, a senior associate with the Mexico Center at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

Wilson and others say Mexico’s ascension is a combination of low labor costs, a shift to an export-based economy in which 80 percent of vehicles produced in Mexico go to the powerful U.S. market, a well-defined NAFTA corridor, and modern factories that are more efficient and safe. An influx of banks has provided workers with greater access to credit.

“It´s gotten to the point where you really have this pipeline of investment in Mexico that includes just about every major manufacturer in the world,” said Wilson, who leads research and programming on regional economic integration and U.S.-Mexico border affairs.

Few gains to broader economy

But Mexico’s fast-rising Motor Cities are still vulnerable to the pitfalls that Detroit has faced as consumer trends shift and the global auto market becomes ever-more competitive, with companies continuing to search for the cheapest and most efficient source of labor.

And for all of Mexico’s trade gains with its U.S. and Canadian partners, NAFTA has yet to produce a significant boost for Mexico’s overall economy. "Most studies after NAFTA have found that the effects on the Mexican economy tended to be modest at most," a 2010 Congressional Research Service report found.

Unemployment is actually higher in Mexico than when NAFTA passed, and efforts to reduce poverty have moved slowly compared with other Latin American countries. Mexico’s per capita income remains under 20 percent that of the U.S.

Journey to NAFTA

Mexico’s rising auto fortunes started years before NAFTA, as the nation was reeling from the so-called “lost decade” of the 1980s. The country experienced a huge debt crisis and zero growth, said Jonathan Heath, former chief economist of HSBC in Latin America. Like many Latin American countries, Mexico followed a closed-door economic policy, choosing to “import less and depend less on the rest of the world,” Heath said. “But it really wasn’t working and so we decided to go after more of the Asian model which was export growth.”

The government moved to privatize over 1,000 government-owned enterprises and open its economy. By the late 1990s, pushing the export model helped Mexico climb out of debt and the automotive industry was the one ticket out of it.

NAFTA created the largest free trade zone in the world, easing tariffs and freeing up trade between the United States, Canada and Mexico. Brushing aside labor objections, President Clinton predicted NAFTA would create 200,000 jobs for Americans in the first year alone, on the premise that as demand for American exports rose, so too would the overall economy.

Two decades later, there is little consensus on NAFTA’S legacy.

Trade among the U.S., Mexico and Canada has increased, while promised U.S. jobs failed to materialize. And the products being exported are increasingly likely to be produced in Mexico and shipped back to the U.S.

Products made in places like Saltillo.

Saltillo: pequeña Detroit

Tereso Medina Ramirez, president of the Confederation of Workers in southeast Coahuila, the largest union in the state, noted that before NAFTA Saltillo was a small city known more for its colonial architecture and ceramic tiles. In 1980 Medina Ramirez got his first job in the auto industry when GM opened a plant there. A few years later, Chrysler followed suit.

By the late 1990s, Saltillo was booming and companies became desperate to find workers, even searching other parts of Mexico to recruit. Under a federal loan program to help workers buy homes, known as INFONAVIT, some 10,000 workers from the southern Mexican state of Veracruz migrated to Ramos Arizpe, the suburb north of Saltillo.

Ramos Arizpe has grown three-fold since NAFTA’s passage, Medina Ramirez said. “Little by little, Saltillo was becoming like a little Detroit.”

To lure more auto business, the government opened the Universidad Tecnologica de Coahuila in 1995. University officials went directly to U.S. automakers and their suppliers to learn their needs and adjust the school’s curriculum accordingly, said university president Raul Martinez Hernandez. In return, the companies ensured that students would be paid for on-the-job training and receive jobs upon graduating.

“We have to know for sure that the students are going to get work after they leave,” Martinez Hernandez said.

Students attend classes at UTC for two years to become plant technicians, spending four months at a time in workshops to learn how to use equipment that they would find in any automotive plant. They spend another four months working full-time at nearby factories. During their first factory stint, wages are paid directly to the university, which in turn pays for students’ health insurance and contributes to the IMSS, Mexico’s equivalent of Social Security. Martinez Hernandez said about 80 percent of graduates go on to work in local auto factories.

Five years ago, UTC added an engineering program, admitting 3,000 students a year. Students must complete the two-year technical curriculum and work full-time on factory assembly lines for a year before returning to pursue engineering degrees. A majority of those in engineering continue to work full-time.

On average, technicians take home the equivalent of just over $900 a month. Engineers, roughly $1,200.

The risks of globalization

Experts predict continued growth for Mexico’s auto factory towns, but some worry that cities like Saltillo are taking the wrong approach to attract global companies, while ignoring smart city planning.

Onesimo Flores Dewey, a lecturer in urban planning and design at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, is originally from Saltillo. Though the increased presence of global manufacturing companies has brought stable, well-paying jobs to the region, he fears Saltillo is becoming too dependent on the automakers’ success.

“Yes, there are all of these jobs but very little in the way of local entrepreneurship,” Flores Dewey said. “The (global) auto industry is so tightly knitted that it does not allow for one to spin off on his own. The most anyone can aspire to in one’s career is getting a prized position to work in Detroit.”

Before NAFTA, when Mexico’s economy was closed, auto companies were required to work with locally-based suppliers, Flores Dewey said. This created an incentive for local governments and business leaders to work together to ensure urban development had the necessary infrastructure to go along with it.

Now, “there are very few independent voices pressuring the government to properly support public works projects,” he said.

So developers are building neighborhoods in the outskirts of town, which means freeways for workers to commute and a more car-focused lifestyle than Mexican families are accustomed to. “It’s like they’re trying to replicate a Houston or a Los Angeles,” Flores Dewey said.

Some neighborhoods are experiencing abandoned housing and crime as waves of families who took out the government-subsidized INFONAVIT loans end up walking away because they can no longer afford their mortgage.

Home loan struggles

Jorge Hinojosa lives with his wife and three children in one such subdivision on the southern limits of Saltillo. He works for automotive supplier Magna International Inc., where he earns just over $500 a month. About a third of that is automatically deducted to pay his INFONAVIT loan along with a government line of credit for his furniture – known as INFONACOT. After taxes and Mexico’s version of Social Security, the family lives on roughly $125 a month.

For all that, Hinojosa said he is grateful to Magna for hiring him with no more than a high school diploma. “I like my job,” he said. “I didn’t need to have a degree to work here and they give me raises every three months.”

Most INFONAVIT homes in the newer Saltillo subdivisions aren’t completely finished when they go on the market. On one afternoon in July, it was easy to walk into new developments surrounding Hinojosa’s neighborhood for a self-guided tour. The structures are maybe 800 square feet, with one or two bedrooms. They come with no doors, windows or insulation. Those must be bought by the homeowner after the house is sold, often through the INFONACOT loans. Several showed evidence of trespass; empty beer cans and chip bags littered concrete patios. Others were covered in graffiti – abandoned before they were even occupied.

When Hinojosa bought his home 10 years ago, it had one bedroom and he had two children who were still toddlers. When the third child arrived, Hinojosa began remodeling, starting by converting his driveway into a living room and then adding a second floor, where there were to be three bedrooms.

“But I have no money to finish,” Hinojosa said.

The second story remains inaccessible; Hinojosa has not yet installed a staircase. Magna gives employees paid vacations, but Hinojosa can’t afford to take his family on trips. Instead, he uses his vacation to work in construction, helping build more INFONAVIT homes. He owns a pickup truck, but it doesn’t work. Like many of the other tens of thousands of auto workers in the region, he takes a company bus to the factory.

Hinojosa says he doesn’t know what he would do if Magna were to relocate. With only a high school degree, he must compete for jobs that look to UTC for more highly-skilled applicants. And he already knows the risks of working for a global company to provide for his family. Before Magna, he worked at a Coca Cola plant. When the factory relocated to Monterey, about 90 kilometers to the east, he was out of a job and forced to work construction.

Mexico’s win, Michigan’s loss

Like Detroit, Saltillo stumbled when GM and Chrysler entered bankruptcy. Production halted at U.S. auto plants in Mexico for six months. The Confederation of Workers negotiated to get employees 50 percent of their pay during the production shut down. Once they returned, they were forced to take deep pay cuts to keep the jobs in Saltillo.

“I believe that the concessions the union made, our flexibility, were what kept the jobs here,” said Medina Ramirez, the union president. “I was in Ottawa in a conference with the UAW and the AFL-CIO at that time. I was told this flexibility (on salaries) was considered a weakness, but it’s that flexibility that kept the jobs here.”

Medina Ramirez said he recognizes that relying too heavily on one industry leaves the region vulnerable to the same fate as cities in Michigan like Detroit, Greenville or Hamtramck, that were left staggered by auto plant closings.

He recalled that when work at the GM plant halted, the union and Mexican government officials urged appliance companies like Benton Harbor-based Whirlpool to relocate there. Now 6,000 workers in the Saltillo area work for appliance manufacturers, including Whirlpool. Another 8,000 work for steel companies. As as result, the percentage of automotive workers in the region has dropped from 80 percent of the workforce to 60 percent, Medina Ramirez said.

“We're looking to diversify,” Medina Ramirez said, “because we don't want the same thing that happened to Detroit to happen to Saltillo.”

Serena Maria Daniels is a 2014 Ford Fellow at the International Center for Journalists, where she is reporting on the impact of NAFTA in Michigan and Mexico. She has worked at the Detroit News, Chicago Tribune and Orange County Register. Support for this project comes from the International Center for Journalists.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

First generation auto workers take government loans to buy small, stucco homes on the outskirts of Mexican cities like Saltillo. With modest wages, some have trouble making their mortgage payments. (photo by Ricardo Casas)

First generation auto workers take government loans to buy small, stucco homes on the outskirts of Mexican cities like Saltillo. With modest wages, some have trouble making their mortgage payments. (photo by Ricardo Casas) Ernesto Gonzalez talks about his hopes for working in Saltillo's growing automotive industry. (photo by Ricardo Casas)

Ernesto Gonzalez talks about his hopes for working in Saltillo's growing automotive industry. (photo by Ricardo Casas) An instructor at the Universidad Technologica de Coahuila demonstrates machinery to engineering technician students used in a workshop at the Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila campus. (photo by Ricardo Casas)

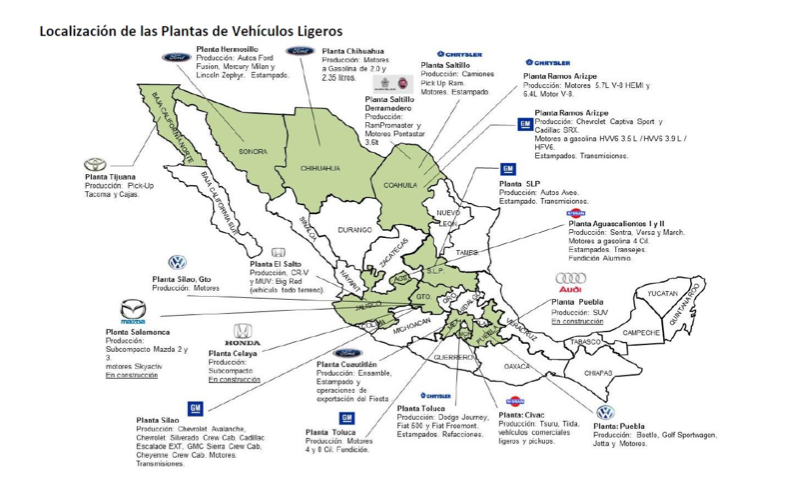

An instructor at the Universidad Technologica de Coahuila demonstrates machinery to engineering technician students used in a workshop at the Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila campus. (photo by Ricardo Casas) You don’t have to know Spanish to see just how deeply U.S. and international automakers and suppliers have embraced manufacturing in Mexico since NAFTA. (credit: Mexican Auto Industry Association)

You don’t have to know Spanish to see just how deeply U.S. and international automakers and suppliers have embraced manufacturing in Mexico since NAFTA. (credit: Mexican Auto Industry Association)