Former Michigan redistricting chair: process 'became all about race'

- Three federal judges appointed by Republican former President George W. Bush began hearing arguments Wednesday in a case that could reshape Detroit’s political landscape

- The lawsuit brought by voters who think the state’s Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission violated the rights of Black voters in Detroit is the biggest test so far of the commission’s work

- Plaintiffs challenge the legislative boundaries for nine state House or Senate seats that include Detroit and its suburbs

KALAMAZOO — The former chair of Michigan’s independent redistricting commission told a federal courtroom Wednesday that race was the dominating factor in determining how metro Detroit legislative districts were drawn.

The testimony came as a three-judge panel in Michigan’s U.S. Western District considers whether Black Detroiters were disenfranchised by the commission’s mapmaking process. It was the first day of a trial that could reshape Detroit's political landscape.

At issue in the trial — the first major test of the state’s new Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission — are nine Detroit-area state legislative districts that have been challenged by a group of Michigan voters who say the districts dilute the political power of Black voters.

Related:

- Do Michigan’s political maps dilute power of Black voters? Trial will decide

- Trial to weigh if Michigan legislative maps discriminate against Black voters

- End may be near for Michigan redistricting panel, a year after finishing maps

The maps drawn by the commission for use in elections until after the 2030 census are, by and large, more competitive than past maps drawn by the Legislature. They gave Democrats a chance in the House and Senate, where they won slim majorities in 2022.

Plaintiffs in a lawsuit seeking a redraw of the Detroit-area districts argue the final product came at the expense of Black Detroiters, whose districts now expand well outside the majority-Black city into neighboring majority-white communities.

But even as the 13-member commission itself is currently spending millions of dollars to defend the state House and Senate maps, some of the members of that commission were among the first witnesses to testify against it.

Among them was former chair Rebecca Szetela who told the court that Detroit’s political district maps could have been better.

In hindsight, she said, the commission relied too heavily on advice from its lawyers and from experts hired to navigate compliance with the 1965 federal Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices, including legislative districts that limit the power of Black voters.

Testifying Wednesday, Szetela claimed the redistricting process "became all about race" due to the expert recommendations provided and ultimately resulted in commissioners aiming for specific percentages of Black voters in metro Detroit districts out of fear that majority-Black districts would run afoul of the Voting Rights Act.

Szetela, a former chair of the commission and one of its nonpartisan members, told the court that she felt the end result of Detroit-based districts extending well into the suburbs didn’t align with the needs of voters, adding that some districts extended so far out of the city they looked like "spaghetti noodles."

“I think the plan should be revised, and I think it can be revised,” Szetela said.

Other commissioners the court heard from Wednesday were less certain that race was the main factor in their decision making, but acknowledged the commission’s strategy of spreading the city of Detroit among several political districts was not what the community wanted.

“We wanted to get it right … what right is, is hard,” said M.C. Rothhorn, a Democratic commissioner.

Commissioner Juanita Curry, a Detroit Democrat, said she didn’t think she and other Black Detroiters “got a fair deal,” but it didn’t occur to her that race was the predominating factor in those decisions.

The three judges who began hearing the case this week — all appointees of former President George W. Bush, a Republican — will determine whether the commission “went too far” in lowering percentages of Black voters in the Detroit area.

In opening arguments, attorneys for the plaintiffs laid most of the blame on the commission’s hired experts, Lisa Handley and Bruce Adelson, who advised the commission on partisan fairness issues and on compliance with the Voting Rights Act.

John Bursch, an attorney for the Black voters challenging the maps, argued that the experts lacked sufficient data on how lowering the number of Black voters in Detroit districts would impact primary elections. That, he said, swayed the commission to draw districts using race as a primary factor that ultimately splintered the Black community and diluted their voting power.

“The cake was already baked based on the racial focus,” Bursch told the court, further arguing the commission “lacked the courage” to challenge their experts and “slavishly adhered to the targets” recommended to them regarding the percentage of Black voters necessary to ensure their preferred candidate would advance.

Before last year’s elections, there were 15 Black lawmakers in the state House and five in the state Senate. After the 2022 election that used the new maps, those numbers fell to 14 in the House and three in the Senate.

The commission has defended the legality of its districts, arguing that Black Detroiters can still elect their candidates and actually have more voting power than before, as their communities are no longer packed into the smaller number of districts they had with the Republican-drawn maps that were in place from 2012 to 2020.

Historically, partisan mapmakers have “packed” districts by including more than 50 percent minority voters. Doing so increased the likelihood that a minority-preferred candidate would be elected — but districts were sometimes so packed with people of color, that it diluted their voting power, limiting it to a lower number of districts overall.

The independent redistricting commission — made possible by a 2018 voter referendum that, for the first time, put an independent body of randomly selected Michiganders in charge of drawing districts — operated under the theory that candidates of color could still be elected by “unpacking” districts, reducing minority representation to less than 50 percent while still making them a significant voting bloc. The thinking was that previous elections showed significant crossover between Black and white voters in metro Detroit.

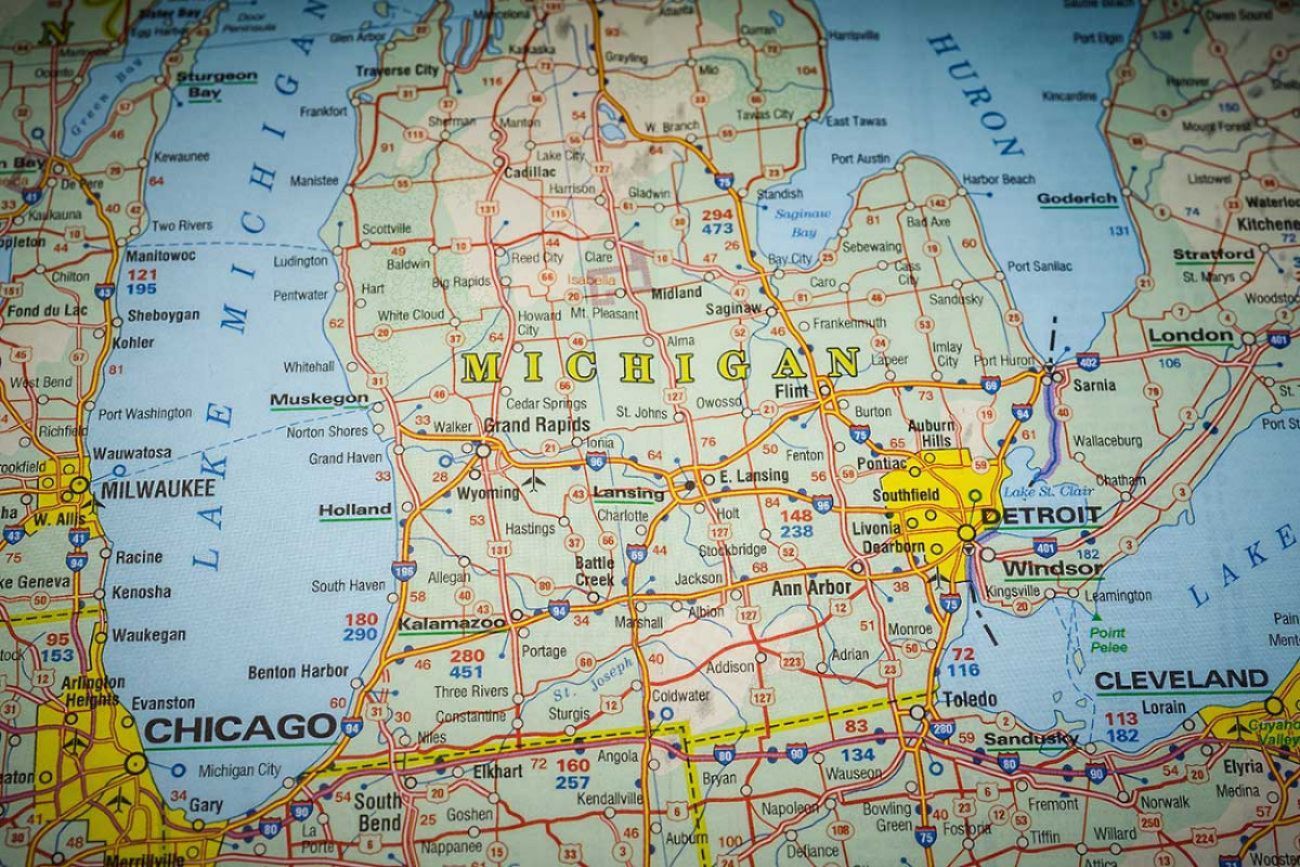

In the state legislative maps, the commission split the city among several districts that extend deep into the suburbs in Oakland and Wayne counties. Detroit voters are now spread across eight of the state’s 38 Senate districts and 15 of the state’s 110 House districts.

Katherine McKnight, an attorney for the commission, told the court Wednesday that commission members did the best they could with the resources available to them, and extended Detroit-based districts into the suburbs because the commission couldn’t meet its legal requirements otherwise.

“It turns out redistricting is difficult no matter who does it,” she said.

Districts on the list for scrutiny are House Districts 1, 7, 10, 12 and 14 and Senate Districts 1, 3, 6 and 8.

The three-judge panel — Judges Raymond Kethledge, Paul Maloney and Janet Neff — will hear their arguments for nine districts total at trial, but rejected similar claims made in four other House districts and three other Senate districts.

The judges were mostly mum Wednesday as they listened to testimony, but Neff asked some commissioners about whether there was a “hard and fast number” they used to determine the racial makeup of state legislative districts.

Most referenced estimates provided to the commission by Handley that Black-preferred candidates would be elected in Wayne County districts where between 35-40 percent of the voting age population was Black.

The trial could last up to a week, and the panel is expected to hear from more commissioners, their hired experts and other witnesses in the coming days.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!