The only high school sport where every kid can go pro

FLINT - On the same day Michigan State University did battle in football with the University of Notre Dame, another game was unfolding at Kettering University in Flint.

With the focus of a quarterback at the line, senior Ben Slade of International Technical Academy in Pontiac hoped that a complex play would go as designed. The challenge: Construct a self-guided robot using designated gears, software and assorted framework that would accurately fling Frisbees into netted target slots. He and his high school teammates already had logged thousands of hours over six weeks as they applied principles of math, engineering and computer programming to the task.

Slade, 17, said it is easy to forget in the heat of competition just how much he is learning.

“This is actually loads of fun. I get up at five in the morning on Saturdays to do this,” he said.

He looked over at the somewhat battered team robot, noting with pride: “I wrote the code for that.”

Called FIRST Robotics, the all-day event on Sept. 21 convened 42 teams of Michigan high school students in a boisterous, intense, celebration of all things nerd. Later that day, a three-team alliance whooped with pride as it was named the winner.

But those behind the program say there is more at stake here than trophies or medals or even the result of a major college football game.

“We are in trouble as a nation,” said Bob Nichols, Kettering's director of alumni engagement. He was speaking to oft-cited evidence that Michigan and the United States lag behind many countries in science, technology, engineering and math – the cluster of subjects known as STEM.

“We just don't have enough students going into STEM careers.”

In 2010 rankings from the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, 15-year-old U.S. students scored 17th in science achievement and 25th in math out of 34 countries. A 2009 report from National Assessment of Education Progress found that just 1 percent of U.S. fourth grade and 12th grade students and 2 percent of eighth grade students scored in the highest level of proficiency in science.

U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan called those findings “an absolute wake-up call for America.”

FIRST Robotics, Nichols believes, is one good way to begin to answer that call.

“I don't just think that it's true. I have proof of it. I have seen the transformation so many times,” Nichols said.

Since 1999, Kettering has awarded scholarships totaling $3.5 million to FIRST participants. Many have gone on distinguish themselves in fields like engineering and science, Nichols said.

A 2005 study by Brandeis University underlined its promise.

In an analysis of 173 FIRST Robotics participants from New York City and Detroit area high schools, it found that 99 percent had graduated from high school and 89 percent went on to college. Nearly 90 percent took at least one college math course and 78 percent took at least one science course. About half took at least one engineering course.

Nearly 60 percent reported they had at least one science or technology-related work experience, while 13 percent received grants or scholarships related to science or engineering. Of those reporting a major, 41 percent selected engineering, compared to a national average of 6 percent.

Founded in 1989 by New Hampshire inventor and entrepreneur Dean Kamen, FIRST grew by 2011 to more than 2,000 teams from around the world. Competitions challenge teams, with the help of volunteer professional mentors, to solve a common problem in a six-week time frame using a standard parts kit and shared set of rules.

Aaron Stewart, 23, competed on a high school FIRST Robotics squad in southern Michigan in 2008 and 2009. He graduated from Notre Dame University in May with a degree in mechanical engineering and was recently hired as an engineer for Whirlpool.

“I definitely learned a lot,” Stewart said of his FIRST Robotics experience. He is now a mentor for the same team that sparked his interest in engineering.

“It's hands-on. You have a real-world problem to solve. You actually go through the details of working out a problem from start to finish.”

That kind of connection is more than coincidence, in the view of another FIRST Robotics advocate.

“We have a saying, 'We are the only varsity sport where everyone on the team can turn pro,'” said Gail Alpert, president of FIRST in Michigan, a nonprofit organization that aims to see FIRST Robotics teams at every high school in Michigan.

“If can we can make FIRST Robotics a sport that gives the prestige of football, then we are significantly changing the culture in the United States.”

Given that he campaigned as “one tough nerd,” it is no surprise Gov. Rick Snyder backed his enthusiasm for this endeavor with $3 million in the 2014 school aid budget to expand FIRST Robotics in Michigan. About one-fourth of Michigan high schools have FIRST Robotics teams, a portion expected to rise in 2014.

Bryan Coburn, 23, earned his FIRST Robotics stripes a few years back while a student at Schwartz Creek High School. The experience taught him about electrical engineering, how to design and build a prototype – and how to attack a problem.

“Before that, I really had no experience with engineering,” he recalled.

He earned a scholarship to Kettering University, where he was student body president. Following his graduation in March, he was hired as a structural engineer for American Airlines.

Coburn doubts he would be where he is today had he not competed in FIRST Robotics.

“With FIRST, you are given a problem at the beginning and you have to develop some sort of way to approach that problem. It showed me how much I enjoyed that process.

“It showed me where my passion was,” he said.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

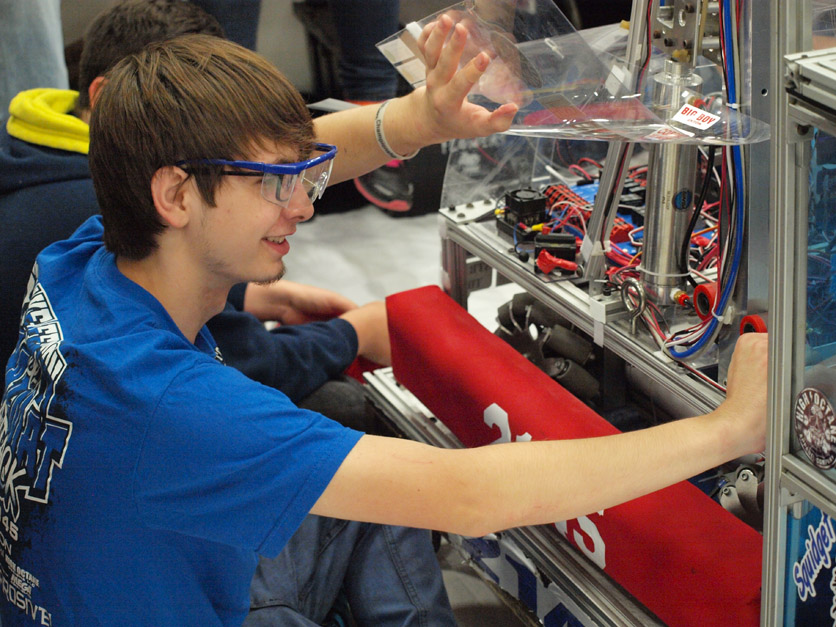

Nicholas Knoch from Lake Fenton High School tightens the bolts of his team’s robot at the FIRST Robotics Competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University. His team is the Lake Fenton Hazmat.

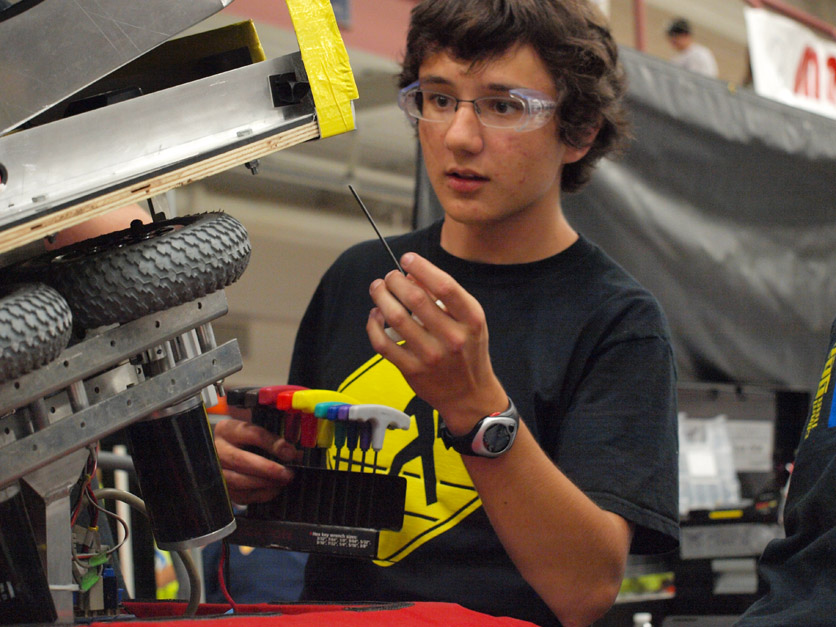

Nicholas Knoch from Lake Fenton High School tightens the bolts of his team’s robot at the FIRST Robotics Competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University. His team is the Lake Fenton Hazmat. Thomas Lombardi, 17, from Grosse Pointe North and South High School, is tinkering with his team’s robot at the FIRST Robotics Competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University. His team is the Gear Heads.

Thomas Lombardi, 17, from Grosse Pointe North and South High School, is tinkering with his team’s robot at the FIRST Robotics Competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University. His team is the Gear Heads. Thomas Lombardi, 17, from Grosse Pointe North and South High School, is getting the team’s robot ready for the next battle at the First Robotics competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University.

Thomas Lombardi, 17, from Grosse Pointe North and South High School, is getting the team’s robot ready for the next battle at the First Robotics competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University. Ellen Green, 17, from Notre Dame Preparatory School, makes sure her team’s robot is ready for battle at the FIRST robotics Competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University.

Ellen Green, 17, from Notre Dame Preparatory School, makes sure her team’s robot is ready for battle at the FIRST robotics Competition in Connie and Jim John Recreation Center on the campus of Kettering University.