What does good teaching look like? We’re about to find out

Imagine a Michigan where student teachers learn at the knee of the state’s best teachers; where master teachers descend into the most needy schools like SWAT teams; where struggling teachers get the training they need to improve, and where everyone knows which teacher colleges turn out all-stars, and which producing duds.

Now imagine a Michigan where schools are paralyzed by lawsuits; where teachers are fired because of inaccurate data; and where students spend more and more time studying for a standardized test.

That’s the promise and the peril of teacher evaluation reform.

Education is the economic engine of Michigan, and nothing inside school walls has as big an impact on learning as teacher quality. Scrambling to improve teacher quality, Michigan is barreling toward a teacher evaluation system on steroids – high stakes, more time intensive, with impact far beyond the teachers being evaluated. The ripple effects could have a major impact on the colleges and universities that train teachers in the state.

The push for a system in which teachers are more realistically assigned to different rating categories has gained urgency as Michigan students have fallen to the bottom tier of states in national testing over the past decade.

Michigan school districts are already required to develop comprehensive teacher evaluations based in part on student learning. A proposed statewide evaluation system, which districts can use instead of their own, was developed at the request of the Legislature by the Michigan Council for Education Effectiveness. The group’s report was released this summer.

While details of the statewide system are still being written, it is expected to be one of the most rigorous in the nation with up to half of a teacher’s performance score based on student growth, and much of the rest based on multiple, in-depth classroom observations and discussions with school leaders.

While almost every state is experimenting with some form of teacher evaluation reform, no one is sure yet how well it will work. But almost everyone agrees it will be an improvement over the old system, where virtually all teachers were judged to be proficient or better and few received any meaningful feedback that would improve their classroom instruction.

“Some of these measures have instability and aren’t perfect,” said Sarah Lenhoff, who, as director of policy and research for Education Trust-Midwest, an advocacy group, is familiar with the Michigan legislation being crafted. “But the old evaluation systems were more imperfect.”

Riding a wave of reform

Historically, principals have performed only cursory evaluations of teachers, often once a year or less. Those evaluations typically provided little guidance to teachers about how to improve. Virtually all teachers received positive scores. The result: schools seldom identified struggling teachers, or rewarded truly high-performing educators.

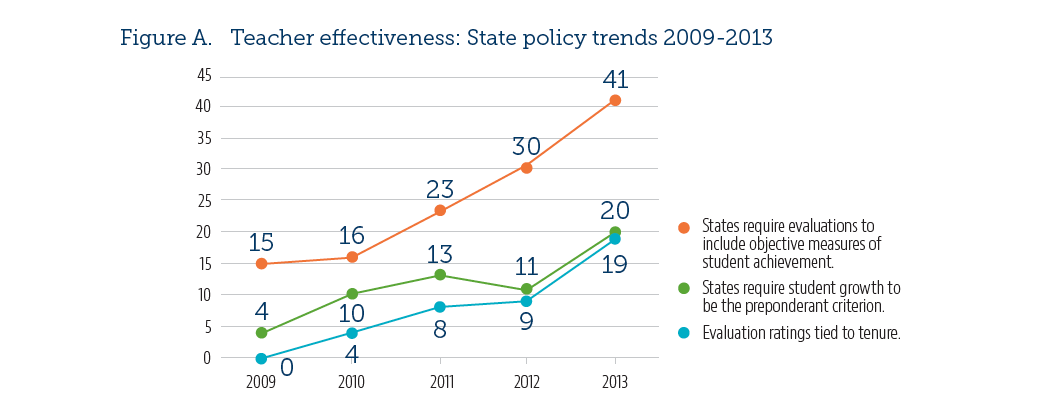

In 2009, only four states required teachers to be evaluated even to a minor degree on whether their students were learning, according to a report issued last week by the National Council on Teacher Quality. And no states tied evaluations to tenure, pay or layoffs.

Just four years later, 35 states require student achievement to be a significant factor in teacher evaluations.

“This is not typical,” said NCTQ vice president Sandi Jacobs. “Big policy shifts tend to be very slow.”

NCTQ’s analysis of teacher evaluation in 50 states found:

- 28 states require annual evaluations of all teachers

- 41 states require some objective measure of student learning.

- 20 states use measurements of student growth as the largest factor single factor in teacher evaluations.

- 18 states base tenure decisions, at least in part, on how much students learn in a teacher’s classroom.

Teachers would be evaluated based on measures of a student’s academic growth either from one academic year to the next, or from fall to spring. The raw scores would likely be adjusted for various factors, such as poverty, so that teachers willing to teach in low-performing, low-income schools aren’t unfairly punished, and teachers in high-performing, affluent districts aren’t presumed to be superstars

Many states, like Michigan, are still implementing reforms. Even states with the most established evaluation reforms have only a year or two under their belts.

“It’s too early (to tell what works),” admits Jacobs.

High anxiety in the classroom

Not knowing how, and how well, reforms will work is causing anxiety among teachers, some of whom see evaluation reform as a way to get rid of teachers now protected by tenure. Firing a few bad teachers is the most common and least accurate description of the rationale behind teacher evaluation reform. In Michigan, teachers who receive the lowest rating two years in a row can be fired, but the number of teachers who would be dismissed in that fashion is tiny, says Joshua Cowen, MSU Associate Professor in the College of Education.

Cowen co-authored a study in Florida that concluded that “even very bad teachers might score above the threshold in one of two years due to random fluctuation in the estimates of their effectiveness… and many ineffective teachers will remain unidentified.”

That may not matter, Cowen told Bridge, because most ineffective teachers leave the classroom on their own accord.

Teacher evaluations that measures student growth “will remove some people,” Cowen added. “But will it remove enough teachers to improve teacher quality? No state is far enough along to answer that question yet.”

In Chicago, a teacher evaluation system based in part on student learning increased the percentage of teachers rated unsatisfactory from 0.3 percent to 3 percent, according to Tim Knowles, director of the Urban Education Institute at the University of Chicago. That’s a ten-fold increase, but it’s still only 3 percent.

Far fewer than 3 percent would likely receive ineffective ratings two years in a row, if Michigan’s evaluations follow the pattern of Florida, Cowen said.

More, though, could lose their jobs through layoffs rather than dismissals, now that Michigan can target teachers with the low evaluations instead of low seniority.

“There’s a huge amount of anxiety among teachers,” said Knowles, of Chicago. “They think, ‘When it comes down to it, my evaluation depends on what students do in the 45 minutes of literacy in the math section of a standardized test.’”

That anxiety remains high, but is beginning to decline, in U.S. schools where student-growth teacher evaluations have already been conducted.

Teachers in Chicago went on strike two years ago in protest of teacher evaluations that factor in student test scores (at a far lower percentage of their evaluations than the 25 percent applied in Michigan initially, and the 50 percent applied beginning in 2015-2016.) After one year, though, “there was overwhelming positive response from administrators and teachers,” said Sue Sporte, director of research for the Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research. “Teachers felt it didn’t remove all subjectivity, but was better than the old system.”

Teachers in Tennessee, where beefed-up teacher evaluations that include student growth have been in place for three years, view the system more positively now than when it began. Still, half of teachers say they remain unconvinced of the value of the reform.

“The primary purpose of an evaluation cannot be to fire, punish or embarrass,” said Deborah Ball, dean of the School of Education at the University of Michigan, who led the 18-month effort to develop the teacher evaluation proposal now being drafted into a bill by the Legislature. The purpose, she said, is “to build a system where every student gets an excellent education every day of every year.”

Impact far beyond job reviews

If that happens, the feedback teaches receive on their job reviews will be only part of the reason. The potential ripple effects of the data collected for those reviews could also reshape how Michigan builds its next generation of teachers.

The state eventually wants to track how teachers educated at state colleges and universities perform on their evaluations. This information will help the state demonstrate which colleges are producing the best teachers, and which are producing the worst. The state could then move to shore up or shut down low-performing schools.

The data might show for instance that Eastern Michigan produces great elementary school teachers, but that its teachers in high school chemistry struggle in the classroom. EMU could then move quickly to beef up its chemistry teaching program.

The data could also benefit student teaching programs. Today, there is no system in the state to assure that student teachers are placed in the classes of the best teachers.

The data produced from these new evaluations will allow the state for the first time to spot Michigan’s true teaching superstars, and route the next generation of teachers to their classrooms (and away from classrooms where student teachers will learn the wrong lessons).

Schools where children are most in need of high-performing teachers are typically low-income, high-minority schools with high turnover and young, inexperienced teachers, a pattern that ends up widening the state’s achievement gap.

With better information on top teachers in hand, the state could recruit teams of principal and teacher superstars for schools where they can make the biggest difference.

Open that wallet

None of these evaluation reforms will work without time, persistence and money.

Principals and other school leaders will need extensive training to reliably conduct the classroom observation portion of teacher evaluations. That training is essential to make grading as consistent as possible – so that a highly-effective teacher rating means the same thing in Grand Rapids as it does in Port Huron.

“One of the key factors in the whole process is having evaluators properly trained,” said Nancy Knight, spokesperson for the Michigan Education Association, the state’s largest teacher union.

That training is expensive – as much as $32 million, according to the University of Michigan Prof. Brian Rowan, who is part of a team assessing the teacher evaluation pilot programs conducted in a handful of Michigan districts during the 2012-2013 school year.

The new evaluation process will be far more intensive, with the principal spending perhaps 10 hours during the school year on each teacher – visiting their classroom, writing detailed reports, and meeting with each teacher to give meaningful feedback on their instruction. In a high school with more than 20 teachers, evaluations alone could take up more than a month, making it likely – even essential – for other top administrators, and the school’s top teachers, to help with observations.

‘Everybody wins’

Senate Education Committee Chair Phil Pavlov, R-St. Clair Township, a longtime proponent of evaluation reform, knows there’s a lot of anxiety among teachers. “More than anything, we need to do a better job to make sure that, number one, the teaching professionals in Michigan know it’s a way to elevate the craft of teaching, and not trying to be a punitive measure,” Pavlov said.

He supports the reform, but is in no rush to push it through the legislature. “I don’t think it’d be fair for the Legislature to start passing legislation that affects so many teachers until we can address all the concerns,” Pavlov said. “We need to be deliberate about it.

“If we do this right, everybody wins.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Source: National Council on Teacher Quality

Source: National Council on Teacher Quality