Henry Ford and the Jews, the story Dearborn didn’t want told

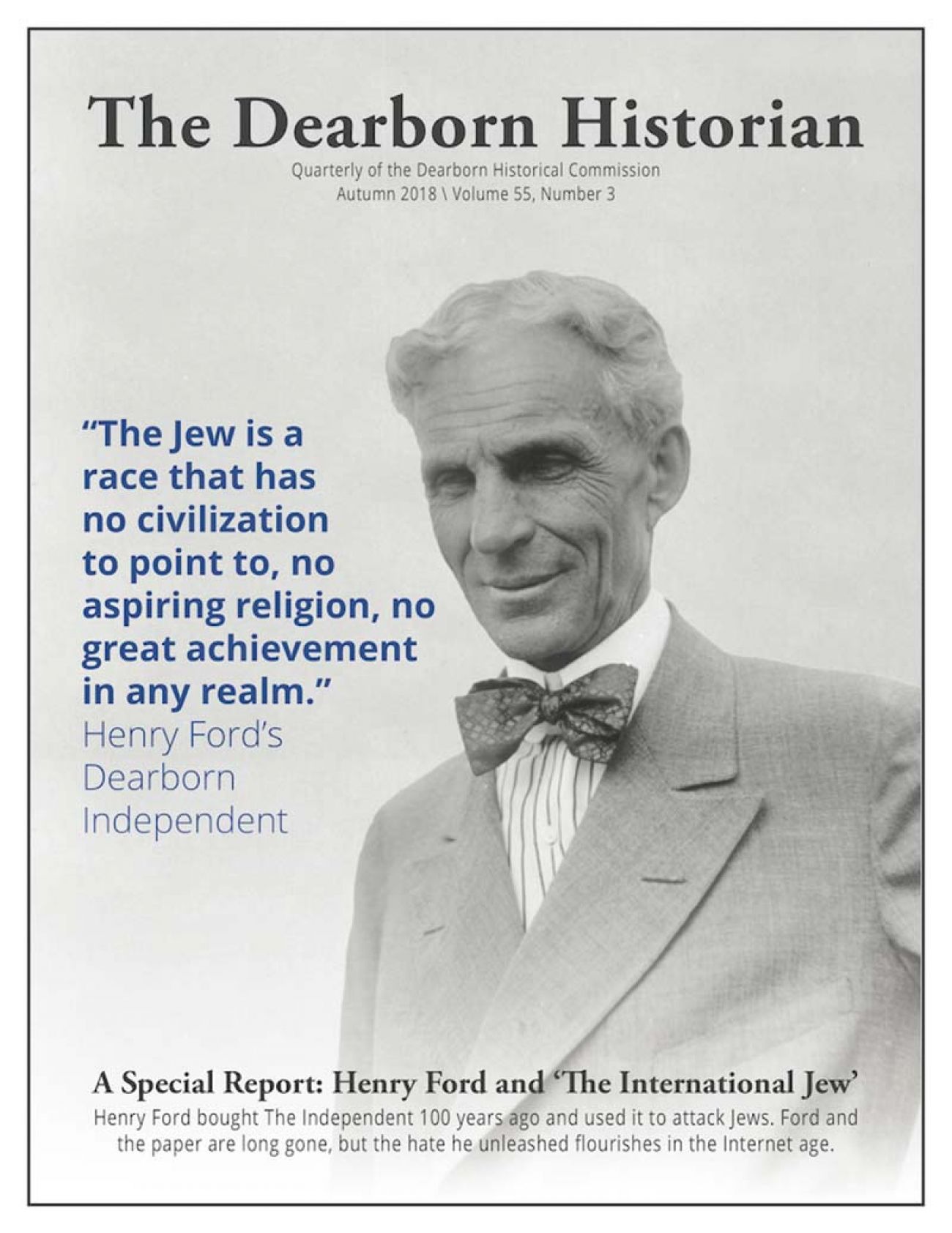

Editor’s note: Last week, the “Dearborn Historian” quarterly journal (circulation 230) published a 3,700-word examination of auto pioneer Henry Ford’s campaign a century ago to foment anti-Semitism far beyond his hometown. Bill McGraw, the Historian’s editor, chronicled how attacks on Jews by the Ford-owned Dearborn Independent newspaper influenced Adolf Hitler and have since found a receptive audience in neo-Nazis and white supremacists today.

But before the Dearborn Historical Museum could distribute the article, Dearborn Mayor John O’Reilly ordered the issue recalled and fired McGraw. The mayor called the article a “distraction” that lacked “a compelling reason directly linked to events in Dearborn today.”

This is not the only recent instance in which a public official sought to squelch an article they found uncomfortable or “off message.” In June, then-Michigan State University Acting President John Engler ordered MSU’s alumni magazine to scrap a cover story on the psychological wounds stemming from the school’s inaction after several women reported being sexually assaulted by Dr. Larry Nassar. Engler had the story revamped to focus on “positive” reforms since he took office.

Bridge Magazine supports efforts to ensure that serious journalism finds a broad audience in Michigan. McGraw, a former Bridge writer and member of the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame, offers a fascinating portrait of an iconic Michigan figure, warts and all. Bridge is proud to follow Deadline Detroit in republishing McGraw’s account.

Opinion: Fired Dearborn editor on why Henry Ford bigotry story matters

Henry Ford and ‘The International Jew’

Chapter 1: Mass-Producing Hate

Henry Ford was peaking as a global celebrity at the conclusion of World War I, having introduced the $5 workday, assembly line and Model T ‒ revolutionary changes that transformed the way people lived. Reporters staked out the gates of his Fair Lane mansion. Ford loved the limelight and he constantly made news, even running for the U.S. Senate in Michigan as a Democrat in 1918. He narrowly lost.

In the midst of his fame, Ford became a media mogul of sorts, forming the Dearborn Publishing Company and purchasing the sleepy Dearborn Independent weekly newspaper, which was dying of red ink. He published the paper under his name for the first time 100 years ago, in January 1919.

Related:

- Opinion | My grandfather’s grave is off limits – one soldier’s story

- Custer and other Michigan historical markers may get a history update

Under Ford, the Independent became notorious for its unprecedented attacks on Jews. But Ford’s anti-Semitism traveled far beyond the Dearborn borders. Showing the marketing expertise that had catapulted Ford Motor into one of the world’s most famous brands, Henry Ford’s lieutenants vastly widened the reach of his attacks by packaging the paper’s anti-Semitic content into four books.

What might have been lost to history as an ugly curiosity has proven to be a Pandora’s box, as the Internet age has given Henry Ford’s anti-Semitic literature a powerful new life. Today, his legacy of hate flourishes on the websites and forums of white nationalists, racists and others who hate Jews.

Experts say “The International Jew,” distributed across Europe and North America during the rise of fascism in the 1920s and ‘30s, influenced some of the future rulers of Nazi Germany.

In 1931, two years before he became the German chancellor, Adolf Hitler gave an interview to a Detroit News reporter in his Munich office, which featured a large portrait of Ford over the desk of the future führer. The reporter asked about the photo.

“I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration,” Hitler told the News.

Ford’s anti-Jewish campaign provoked protests and a boycott of Ford Motor automobiles in the 1920s. Ford offered an apology ‒ received by the public with great skepticism ‒ and closed the paper in 1927. It was too late, though, as copies of “The International Jew” spread widely before and after World War II, influencing generations of anti-Semites. The glowing imprimatur of Henry Ford lent credibility to the preposterous charges against Jews the books contained.

But what might have been lost to history as an ugly curiosity has proven to be a Pandora’s box, as the Internet age has given Ford’s anti-Semitic literature a powerful new life. Today, a century after Ford purchased the Dearborn Independent and 72 years after his death, his legacy of hate is stronger than ever ‒ it flourishes on the websites and forums of white nationalists, racists and others who hate Jews.

Today, “The International Jew” by Henry Ford plays a significant role in fomenting resentment as the United States grapples with rising numbers of hate crimes and anti-Semitic incidents, ascendant white nationalism and a gunman armed with an AR-15-style assault rifle who massacred 11 people at a Pittsburgh synagogue in October. When he surrendered, the gunman told police he “wanted all Jews to die.”

An essay posted by the Anti-Defamation League on its website says that by resurrecting decades-old texts such as “The International Jew,” today's anti-Semites demonstrate the longevity of their beliefs, legitimizing them to both dedicated followers and potential recruits.

Because of Ford’s fame, “The International Jew” has been a “particularly powerful tool for haters trying to validate their hostile beliefs,” the essay adds.

Two examples of Ford’s influence online today: On Stormfront, a white nationalist online forum, a contributor has taken the screen name Dr. Ford and uses a photo of Henry Ford as a profile image. On the same forum, a participant whose screen name is AllisonRM wrote last year:

“I'm currently reading The International Jew: Essays from the Dearborn Independent (Ford)… Read these great books!...We, the white race, need to encourage ourselves and our children.”

Heidi Beirich, an expert on extremism in the United States at the Alabama-based Southern Poverty Law Center, said extremist websites contain thousands of references to Ford and “The International Jew.”

“In the world of the racist right, Henry Ford is almost a living, breathing human being, “ Beirich said in an interview. She added that extremist leaders use Ford “as an inspiration” and “validator” to impress people while enlisting them to join the movement.

It’s not just extremist websites that are peddling Ford’s books. Shoppers can buy “The International Jew” by Henry Ford on the websites of Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Walmart.

“This is a wonderful book that should be required reading for all Americans,” wrote Tara, in a five-star Amazon review. “Sadly, many people like to label Henry Ford as an anti-Semite, when nothing could be further from the truth.”

And then there are the ads. After I explored the availability of Ford’s anti-Semitic books on Amazon in connection with this story, ads for “The International Jew” by Henry Ford began popping up on my Facebook page. They appeared next to ads for what I was actually shopping for ‒ a winter coat.

Chapter 2: Transforming a Country Weekly

Starting with the issue of May 22, 1920, Ford began using the Independent to attack Jews. Every week for nearly two years, the paper published articles that assailed Jews for being sneaky and treacherous and conspiring to control the global financial system, a common Jewish stereotype. Ford also accused Jews of scheming to dominate such American industries as Hollywood, farming and liquor distribution.

“There is no other racial or national type which puts forth this kind of person,” the Independent said in June 1920. “It is not merely that there are a few Jews among international financial controllers ‒ it is that these world controllers are exclusively Jews.”

While anti-Semitism goes back centuries, Ford’s salvos were likely the most sustained printed attacks on Jews the world had ever seen. With his wealth and resources, Ford remains the most formidable anti-Semite in American history.

In 2019, many educated Americans have a vague understanding that Ford had anti-Semitic sentiments. Few people are aware of the details, though, of how Ford spent millions on his paper and the “International Jew” series of books.

The books spread like a virus, translated into 12 languages and distributed on three continents in the years after World War I. The books appeared as fascist forces were organizing, especially in Germany, one of the countries targeted by Ford’s agents.

In its first couple of years, Ford sold more than 200,0000 copies of “The International Jew.” His underlings deliberately declined to copyright the content, so other anti-Semites were free to publish the books. That is one reason Ford’s paper and books are widely available today, in printed form and online. With no copyright, it’s nearly impossible to stop their proliferation.

Chapter 3: Henry Ford, Publisher

After paying $1,000 for the Independent (about $18,000 in today’s dollars), Ford named his closest aide, Ernest Liebold, the newspaper’s general manager. Liebold was a hardcore anti-Semite.

“He hated everything Jewish, and he saw the publication as a vehicle for promoting his agenda,” Steven Watts wrote in “The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century.”

Ford and Liebold then assembled a crack editorial team by raiding the Detroit News.

For top editor, Ford hired News’ executive Edwin Pipp, a liberal Catholic who had been a muckraking Detroit reporter known as a soft touch because he wrote stories about people down on their luck. William Cameron, a Canadian immigrant who was a star reporter and editorial columnist for the News, came aboard as the lead writer.

Experts have long debated the roles of these three in the production of the Independent, but a general consensus has emerged that Ford, not a skilled writer, talked over ideas with Liebold, who ordered Pipp and Cameron to transform them into stories. Some historians believe Cameron “undertook his assignment disgustedly,” as David Lewis wrote in “The Public Life of Henry Ford,” adding that Cameron ”was either unable or did not try to dissuade Ford from launching the attack.” However disgusted he might have been, Cameron remained a Ford aide into the 1940s.

In serving as the link between Ford and the rest of the world, Leibold was strategic and menacing. With Ford’s money, Liebold organized a network of spies, many with government intelligence backgrounds, to snoop around outposts of Jewish life in America, paying special attention to community leaders. The agents funneled the information to Liebold in Dearborn as grist for the Independent’s anti-Jewish campaign.

Henry Ford ordered that the Independent not be used to publicize him or the company, though the paper’s nickname was “The Ford International Weekly” and Ford forced his dealers to conduct subscription campaigns. Some dealerships threw a copy of the Independent into newly sold Model Ts. Circulation eventually reached 900,000, making it one of the biggest periodicals in the country.

The Independent carried a weekly column by Ford ‒ verbosely ghost-written by Cameron – that filled “Mr. Ford’s Page.” Ford commented on many everyday subjects, but virtually never used his column for the most blatant anti-Semitic content. The Independent’s attacks on Jews ran separately, often starting on page one, almost always without a byline.

Under Ford, the Independent was tabloid in form, cost five cents and ran 16 pages. Its motto: “Chronicler of the Neglected Truth.”

At the beginning, the Independent was unremarkable, filled with long-winded feature articles on national and international subjects such as farming in Europe, the Smithsonian Institute or a cure for leprosy. Most critics found the paper soporific, a Saturday Evening Post without the pizazz.

It was only months, though, before the Independent took a sinister tack. Ford’s pet peeves – distant capitalists, aliens who refuse to assimilate, Bolsheviks (all code words for Jews) ‒ began creeping into the Independent’s pages, according to Neil Baldwin’s 2001 book, “Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate.”

“His own page took on a strident tone as Ford lashed out against unnamed, hidden influences that continued to trouble him,” Baldwin wrote.

Circulation lagged in the early going and Ford lost the equivalent of $3.5 million in today’s dollars in the first year. Staffers knew changes had to be made. “Find an evil to attack,” Joseph J. O’Neil, a veteran New York newspaperman, urged Liebold in a memo. “LET’S FIND SOME SENSATIONALISM,” he typed with emphasis.

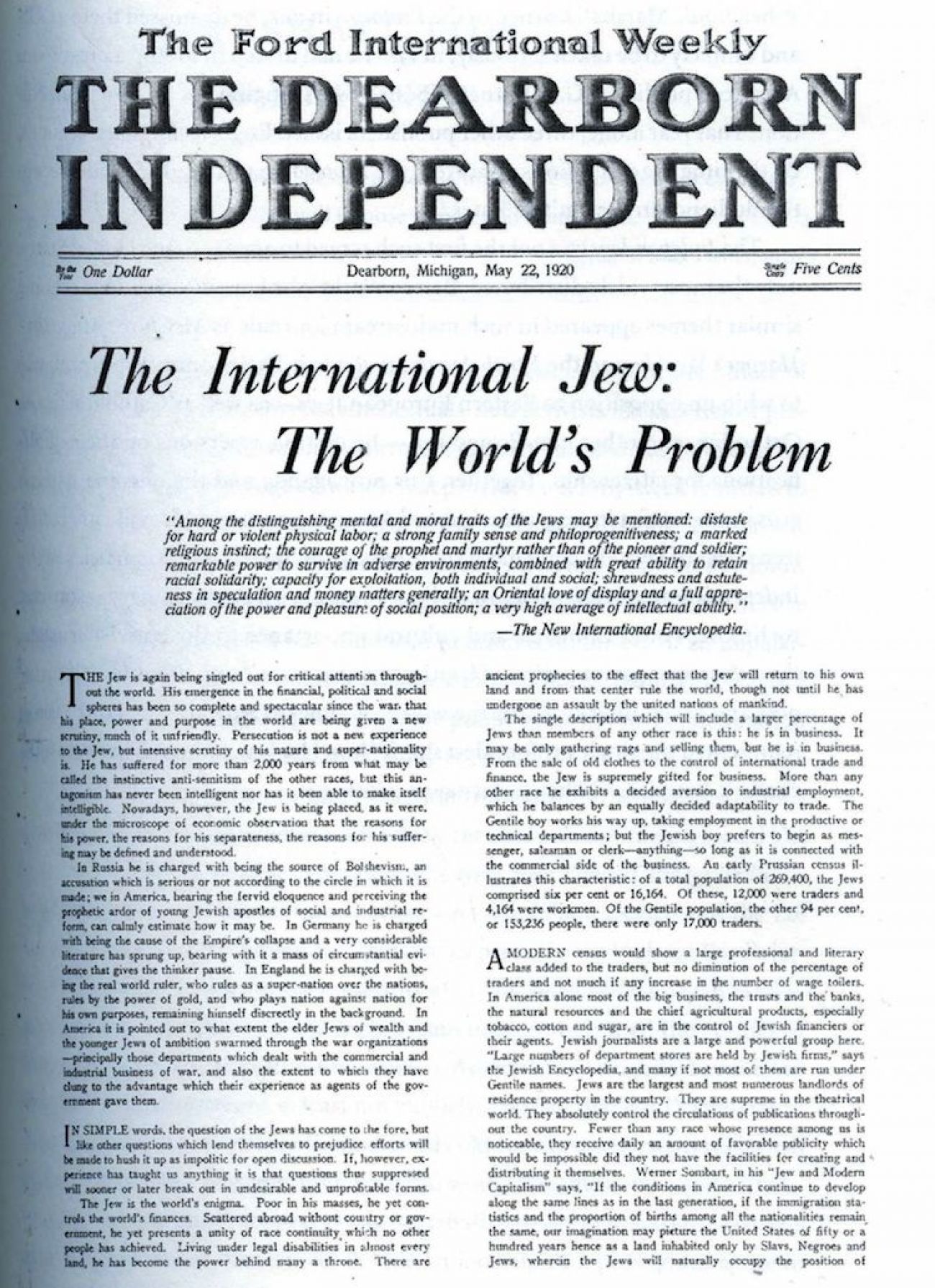

Beginning with the issue of May 22, 1920, Ford found his target. That issue of the Dearborn Independent kicked off a 91-week campaign of insults, criticism and lies directed at Jews from Dexter and Davison in Detroit to Krakow, Poland.

“The International Jew: The World’s Problem,” read the inaugural page-one headline.

“There is apparently in the world today a central financial force which is playing a vast and closely organized game with the world for its table and universal control for its stakes,” the article said.

In subsequent weeks, the Independent hammered Jews for scheming to take over Broadway theater, baseball, American agriculture and countless other domains. Ford’s paper also popularized an early 20th-Century forgery from Russia, “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” which similarly purports to show Jews are bent on world domination.

Chapter 4: Jews and Others Fight Back

The Independent ‒ put out by Henry Ford, Dearborn-born and bred, legendary Tin Lizzie wizard, American folk hero and one of the world’s richest men ‒ shocked Jewish Americans and many other citizens of diverse backgrounds. It wasn’t long before they began to counterattack. The Independent was controversial from coast to coast in its day.

Pipp, whose Catholic conscience would not allow him to run an anti-Semitic journal, quit and began publishing his own paper, Pipp’s Weekly, that was often critical of Ford. Cameron took Pipp’s place. Ford’s wife, Clara, and Edsel, his only child, put off by the anti-Jewish articles, reportedly distanced themselves from the Independent.

As the Independent launched its anti-Semitic campaign and sent the paper, unsolicited, to libraries and schools across the nation, protests broke out. Some cities attempted to ban the paper, but such moves raised First Amendment issues. Jews organized Ford Motor boycotts. Former President William Howard Taft, a future U.S. Supreme Court chief justice, slammed Ford in a speech. Later, he joined outgoing President Woodrow Wilson and dozens of other VIPs in signing a petition that denounced the Independent.

“God help Henry Ford. God forgive him,” said well known New York Rabbi Stephen Wise, who called Ford the “most contemptible little liar that ever lived.”

Louis Marshall, a New York lawyer and towering figure in the American Jewish community, played a key role in combating Ford and the Independent. His first move was to send Ford a telegram, saying the articles “constitute a libel upon an entire people.”

The Independent was unimpressed. “Your rhetoric is that of a Bolshevik orator,” it fired back, linking Jews and Bolshevism, a common anti-Semitic trope.

In Detroit, Rabbi Leo Franklin, the head of Temple Beth El and an outspoken foe of discrimination, found himself caught between Ford and Marshall. Franklin was a Ford friend and former neighbor who had received yearly Model T’s as a gift. Marshall, in Manhattan, urged a more militant approach toward Ford in Detroit that Franklin was slow to adopt. Franklin eventually returned his 1920 Model T and told the Detroit News that Ford “has fanned the flames of anti-Semitism throughout the world.”

Chapter 5: An Independent Target Sues and Ford Shuts the Paper

After nearly two years, Ford suddenly halted the attacks in December 1922. Just as unexpectedly, he resumed them in 1924 when he went after Aaron Sapiro, a young Jewish activist from California who had become a leader in the farm co-op movement.

Sapiro fought back. He filed a $1 million libel suit against Ford, igniting weeks of sensational coverage in the national press. The case came to trial in 1927, though juror misconduct led to a mistrial.

Ford, freed from being forced to testify under oath, a position from which he had embarrassed himself in the past, issued an apology to Sapiro and eventually settled out of court with him. Ford also took back all of his attacks on Jews and withdrew “The International Jew,” though that proved to be much easier promised than done.

In his apology, Ford called himself “deeply mortified” by the attacks, but blamed underlings, denying he knew about the articles in advance. He relieved Liebold and Cameron from their posts at the Independent, but kept them on the company payroll for years. Few close observers ‒ or average Americans ‒ believed Ford was so removed that he hadn’t been aware of prominent articles in his own newspaper that had sparked an international outcry.

In an editorial headlined “Forgiveness without Fawning,” the Detroit Jewish Chronicle echoed many other papers in casting doubt on Ford’s claim that he had been unaware of the paper’s content.

“That Mr. Ford does not accept personal responsibility for the anti-Semitic articles is also obvious,” the editorial said. “His action in this respect is what is commonly known as ‘passing the buck.’”

Ford closed the Independent in December 1927. But the damage had been done.

“Ford’s well-publicized decision was disingenuous,” wrote Victoria Saker Woeste in “Henry Ford’s War on Jews,” because he knew that even after closing the paper, his hate literature already lived on in hundreds of thousands of copies of “The International Jew."

Chapter 6: Why?

Why did Henry Ford ‒ the entrepreneur Fortune magazine in 1999 named “Businessman of the 20th Century” ‒ spend so much time and money attacking Jews?

Searching for clues, because Ford never discussed his anti-Semitism in depth, historians often have focused on his childhood amid the farms of what are now the streets of east Dearborn. While only a long walk from Detroit in the 1860s and ‘70s, Ford grew up isolated from Jews and most other minorities, and 19th-Century rural America was a place where ancient Jewish stereotypes were widespread.

Experts also point to Ford’s close friend, Thomas Edison, who had a complex history of remarks about Jews, and Ford’s close relationship with Ernest Liebold, whose anti-Semitic views were well known. Historian Douglas Brinkley wrote that Ford’s “increasingly vicious anti-Semitism appears to have grown out of his antipathy toward powerful bankers.”

Ford’s criticism of Jews and hatred of Wall Street were “the foibles of the Michigan farm boy who had been liberally exposed to Populist notions,” wrote historian Richard Hofstadter.

“Ford disliked Jews who he believed exercised disproportionate control over the institutions that were vital to the rural-mercantile economy he wanted to build,” wrote Victoria Saker Woeste.

Chapter 7: Ford Family and Company Win Praise for Reparations

The response to Henry Ford’s anti-Semitism by the Ford family and Ford Motor Co. has received considerable praise from Jewish organizations and other observers.

“The Ford family and Ford Motor Company embarked upon correctives even before the Old Man passed away, Neil Baldwin wrote in “Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate.”

On its website, the Anti-Defamation League says:

In the decades following Ford's death in 1947, the Ford family and the Ford Motor Company have engaged in numerous projects and endeavors in the public interest, including many that have been supportive of Jewish concerns.

In 1997, for example, the Ford Motor Company sponsored the first screening of Steven Spielberg's "Schindler's List," commercial-free, on national television. Ford Motor is credited with extending economic credit to the young state of Israel and supporting Jewish charities at home and abroad.

Today, two generations of the Ford family are well represented on the board of one of the country’s most elaborate historical complexes, The Henry Ford, in Dearborn, formerly called Greenfield Village, which Henry Ford founded. The chairman of the board is S. Evan Weiner, of the Edward C. Levy Co. in Detroit, who is Jewish.

In November, Weiner welcomed a largely Jewish crowd of several hundred people in the museum during a one-day collaboration with the Jewish Historical Society of Michigan: “The Henry Ford…Through a Jewish Lens.” The program examined Ford’s bigotry and, through pop-up exhibits, celebrated Jews as American innovators.

Steven Watts, a historian at the University of Missouri and author of “The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century,” spoke about Ford’s exalted place in American culture, but added: “It’s hard to find a more blatant anti-Semite in American history.”

Larry Gunsberg, an officer at the Jewish historical society, told the Jewish News that he found the event “an excellent way for the community to embrace the generational change in the Ford family.”

On the “My Jewish Detroit” website, historical society President Risha B. Ring said, “This monumental conversation is long overdue.”

Chapter 8: Ford and the Führer

Henry Ford’s hate campaign took a disturbing turn in the 1920s and ‘30s, when it intersected with Adolf Hitler’s path to power. The collision produced what the 21st Century calls synergy.

Copies of “The International Jew” began re-appearing in the 1930s in the U.S., South America and Europe, especially in Germany, where the Nazi Party was poised to take power. Books wound up on a table in the office of Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party in Munich.

“Hitler’s ravings and public speeches against Jews frequently were based on Ford’s anti-Semitic literature,” Ford expert David Lewis wrote.

One leading Nazi, Baldur von Schirach, the Reichsjugendführer (Hitler Youth leader) in the 1930s, became an anti-Semite after he read “The International Jew” in German, von Schirach testified at the Nuremberg war-crime trials. Found guilty of crimes against humanity for helping to send thousands of Viennese Jews to their deaths, von Schirach served 20 years in Spandau prison.

“If Henry Ford said that Jews were to blame, why, naturally we believed him,” von Schirach is quoted as saying in Baldwin’s “Henry Ford and the Jews.”

Von Schirach added: “You have no idea what a great influence this book had on the thinking of German youth.”

Numerous historians have noted that Ford is the only American mentioned in Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” memoir. After asserting that Jews were increasingly exerting control over American labor, Hitler wrote, “one great man, Ford, to their exasperation, still holds out independently.”

Experts on Hitler have noted Ford’s literature influenced Hitler’s writing in “Mein Kampf.” Reading “The International Jew,” which became a hit in Germany after being published in German in 1922, helped push Hitler further into “conspiratorial anti-Semitism,” Thomas Weber wrote in “Becoming Hitler: The Making of a Nazi.”

“Henry Ford is important for having provided to Hitler confirmation, coming from the very heart of America, of an idea that had been brewing in his mind,” Weber wrote. The idea was that Jews’ control of global finance was behind the world’s problems.

“Henry Ford thus turned into an anti-Semitic icon for Hitler.”

In summer 1938, with the German Wehrmacht having marched into Austria, and despite years of deflecting charges he was an anti-Semite, Ford accepted a 75th birthday present from Hitler. It was the Grand Cross of the Supreme Order of the German Eagle, the highest award the regime bestowed on foreigners.

The golden Maltese cross, surrounded by four small swastikas, was presented to Ford in Ford Motors’ Dearborn offices by Fritz Haller, the German vice consul in Detroit.

News reports about the birthday present from Hitler triggered a bitter backlash across the nation. Ford apologized, again. And again, people laughed when they read his words.

“Acceptance of a medal from the German people does not, as some people seem to think, involve any sympathy on my part with Nazism,” Ford said.

“Those who have known me for many years realize that anything that breeds hate is repulsive to me.”

We can’t know what was in Ford’s heart when he said those words. Perhaps he was genuinely remorseful. Perhaps he accepted the medal to avoid embarrassing an international diplomat, or for business reasons.

Or perhaps anti-Semitism infected him to the bone, and his apology was as cynical as it seems to many. What we do know is that this chapter of his life, which lasted less than a decade, reverberates a century later in a crude hatred that seems impossible to eradicate. It’s an ugly side of the patriarch of one of America’s greatest families and founder of one of its best-known companies.

And the ugliness won’t go away. In November, a reader left this Amazon review of “The International Jew”:

“It's just amazing how enlightened Henry Ford became while living in a world of jew contrived deception ramping up in the USA. The European converted (fake) zionist jew has conquered amerika. Judaism = communism.”

The reader gave “The International Jew” five stars.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!