Goodbye to Delray, the Detroit enclave residents are getting paid to leave

Blighted but beloved, Delray’s epitaph has been written for years. This time, though, the end is truly near for the Detroit neighborhood – and Maria Walkenbach is so excited to leave she’s already packing.

She’s among the first 10 residents of the enclave of Southwest Detroit to take advantage of a unique home swap program to make way for the construction of the Gordie Howe International Bridge. After years of delays and controversies, the $2.1 billion bridge to Ontario is supposed to begin construction later this year.

Photos: Fond memories and burned homes: That’s Delray, the woebegone corner of Detroit

In exchange for voluntarily leaving, Walkenbach and as many as 350 neighbors will receive a home elsewhere in Detroit owned by the city’s land bank, moving expenses and renovations. The total package is worth up to $60,000 per homeowner, and this weekend, Detroit is hosting its first walk-through of available homes in the Warrendale neighborhood on the city’s west side.

For Walkenbach, 58, the decision to leave her deteriorating home in the northern end of Delray wasn’t difficult. But it doesn’t mean it will be easy to leave the history-rich neighborhood that began as a waterfront village in 1898.

“It used to be a place where everybody watched out for everybody mostly, and we all knew each other,” she said. “It’s going to be empty with nothing there. That’s going to be sad.”

Goodbye Delray, Hello Warrendale

Anchored by Historic Fort Wayne and the city’s wastewater treatment plant, Delray had about 23,000 residents during its heyday in the 1930s. Today, the U.S. Census estimates 2,000 remain, but there likely are even fewer.

A quick tour explains why.

Odors are typical in the neighborhood, either from the wastewater treatment plant or the nearby Marathon Oil refinery and U.S. Steel operations on Zug Island.

For years, the neighborhood has been a favorite of arsonists and illegal dumpers.

Now, those who remain in Delray are split into two groups – those who are being told to leave by the government, and those the government is asking to leave.

Using eminent domain, the Michigan Department of Transportation has acquired 636 parcels for the bridge and toll plazas. Most of the land was purchased through good-faith offers, and the state expects to spend about $400 million on all acquisitions, said Jeff Cranson, a spokesman for MDOT.

At least 200 demolitions in Delray are completed, and other demos are ongoing, MDOT officials said in November.

Those who live on the outskirts of the project's footprint are not being forced to leave, but the city is asking them to swap their home for one to be renovated to their specifications in three neighborhoods: Warrendale, elsewhere in Southwest Detroit and Morningside on the city’s east side.

After residents leave, the city will demolish the homes.

The City of Detroit sold property and roads to MDOT to make way for the bridge and approved a community benefits agreement worth $48 million for job training, neighborhood improvements and health monitoring for Delray.

The city will use $32 million of that money for the Bridging Neighborhoods program to pay for the voluntary relocations – or house swaps – for residents like Walkenbach.

The Detroit swap program had targeted about 300 residents to participate over the next three to five years, and anticipates about 200 will take the offer.

The program also offers home improvements such as new soundproof windows and ventilation for Delray residents who will live near the bridge, said Charity Dean, director of Bridging Neighborhoods.

So far, 55 residents have signed up for the swaps, Dean said. Another enrollment period will open at the end of the year, she said. Dean said the program will likely continue for four years, giving the last holdouts time to weigh the swap against living in the shadow of the bridge (whose construction completion still isn’t clear).

“We think a lot of people are going to wait and see what happens,” Dean said.

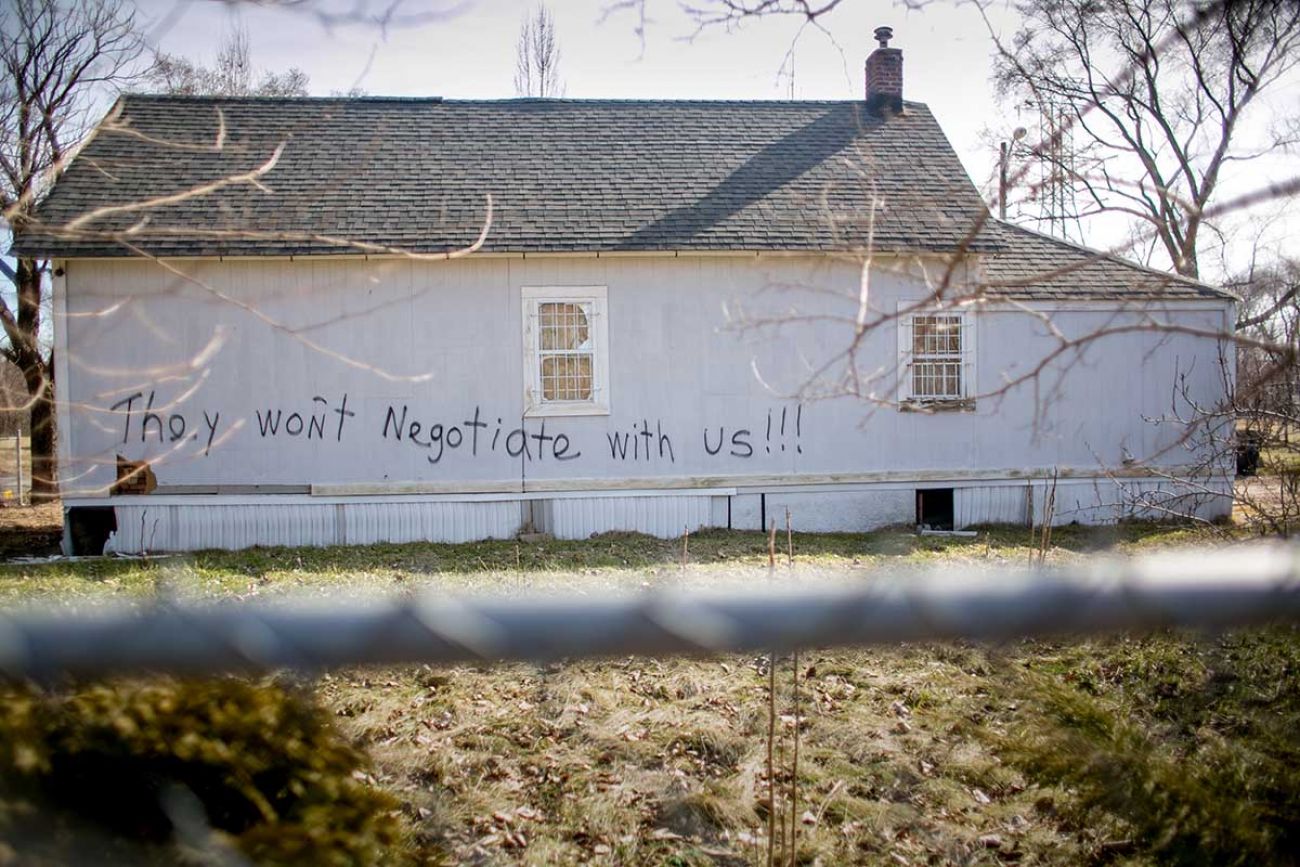

Not everyone is happy. Spray paint on an abandoned house in the neighborhood reads: “They won’t negotiate with us!!!”

John Nagy, a native of Delray and activist for more than 30 years, said the city’s offer leaves out renters and landlords who can’t afford to move.

“The people that are going to be left behind, what kind of quality of life will be left for those folks?” he asked.

“As ridiculous as that sounds, there are people who don’t want to leave. Some are senior citizens. Who wants to start over at that age?”

Eli Clepe is among those reluctant to leave. The 59-year-old sold his two-family flat to the state for $32,000. He’s lived in the neighborhood nearly 30 years, coming to the city from Anaheim, California, because housing was cheap.

As demolitions have cleared blocks of blight, Clepe said his block has become peaceful, almost like a park.

Clepe rented out one of the two units in his building on Crawford Street and lived in the other. He said he would’ve stayed in the area forever if not for the bridge.

“Moving when you’re getting older is a bitch,” said Clepe, a construction contractor. “But we can’t really fight it. We have to go.”

Death by industrialization

At the turn of the 20th century, Delray was an idyllic, rural independent village with a large Hungarian immigrant population, according to a report by the University of Michigan that studied the area and the community benefits agreement.

But Delray’s location on the Detroit and Rouge rivers soon attracted industries from glass and furniture shops to the Marathon refinery.

Delray was annexed by Detroit in 1905. By the 1940s, the neighborhood was a hopping, diverse neighborhood populated by those of Polish, Armenian and African-American heritage. Today, its population is equal parts white, African American and Latino.

Karen Dybis, author of ‘The Witch of Delray,’ a 2017 book about an unsolved 1930s murder in the neighborhood, said the area has been on the decline since more factories moved in during the 1940s.

Wealthier people moved out, replaced by working-class residents who later left along with most remaining industries, she said.

“It’s been a slow death, but for sure, with that bridge, it’s done. They’re removing cultural landmarks,” Dybis said. “You can close the coffin with that bridge going up.

The old hangout Kovacs Bar was demolished last year. Southwestern High School and the feeder elementary schools that the neighborhood revolved around are gone. And just last month, the 114-year-old building that housed the First Latin American Baptist Church was bulldozed to make way for the bridge.

‘I wish everyone .. would leave’

David Williams sat on his porch on Rademacher Street last week, watching cranes clearing brush and dirt from a lot that used to be his neighbors’ homes.

Williams can name the people who live in the only other four houses standing for several blocks, including Clepe.

At the end of his block sits the 170-year old buildings at the historic Fort Wayne. Those will be the only bricks standing soon.

Williams is saying goodbye this month to his weathered, two-family flat that housed generations of his family and has seen better days. He’s moving to Westland. But he’ll be back to Delray to go fishing for bass at the foot of Dearborn Street.

“I look at it like it’s just history,” Williams said of Delray, as he watched the cranes. “We gon’ miss it.”

As for Walkenbach, she said she will be glad to be rid of the the noise from cranes and pollution.

Her husband died five years ago and her house holds too many memories. And this neighborhood where she grew up is not what it used to be since the bridge talks started years ago, she said.

“Once this all started, it’s like Southwest Detroit/Delray was not going to be there much longer so why take care of it?” she said. “It’s like Detroit has forgotten about us.”

She hopes to be moved out by Christmas to a rehabbed house with a basement, front porch and backyard where her three grandchildren can play in her pool and trampoline without bridge traffic rumbling nearby.

“I wish everybody who lived in the area would move,” she said. “It’s time.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!