See how auto companies left trail of pollution, toxins in Michigan

In Michigan, birthplace of the automotive industry, large assembly plants have long served as a symbol of progress and pride.

The pollution those facilities emitted into our air, land and water was easy to overlook when they provided hundreds of millions of stable jobs.

But the heyday is long gone, while the downsides linger.

Related:

- Polluter pay laws coming, following Bridge probe

- Democrats seek new office to aid Michigan with green energy job losses

- Bipartisan vibes as Michigan lawmakers seek to reform SOAR incentive fund

- Watch Bridge’s Lunch Break discussion on Michigan’s industrial legacy

Bridge Michigan has investigated how the auto industry profited in Michigan cities, moved on, and left behind contamination that festers today, harming communities while taxpayers cover the cleanup costs.

Now, the Michigan Legislature may be poised to act, with lawmakers considering bills soon to break the cycle of economic boom followed by pollution and abandonment.

Bridge has told the story through maps, interactive features and profiles of small towns.

Now, we are telling it through photos, most of which were created by David Ruck, a Michigan-based documentary filmmaker.

Lansing and General Motors

In the auto industry’s heyday, thousands of workers filled three General Motors Corp. plants along the Lansing and Lansing Township border. Students at J.W. Sexton High, right, learned to drive in GM-donated cars; workers cheered Sexton’s sports teams from the factory rooftop. (Courtesy R.E. Olds Transportation Museum)

GM closed the plants 18 years ago then demolished them before filing for bankruptcy. The sites still sit vacant, though GM stores vehicles there made at a factory across town. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

PFAS, PCBs and other pollutants were found in the soil and groundwater. Taxpayers have paid $22 million and counting to clean the site up. Until that job is complete, redevelopment prospects remain dim. (Bridge photo by Kelly House)

Nearby resident Carol Garza wonders when the view outside her front door will be anything other than cracked concrete, contamination and blight. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

In addition to the polluted GM plants, Garza lives next to a polluted former auto supplier: Adams Plating, which has contaminated the groundwater with chromium. It’s now a federal Superfund site. Surrounded by pollution, Garza worries about the health of her grandkids when they come to visit. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

As GM exited Lansing Township, its presence expanded into the farm fields of Delta Township, 7 miles away. In 2006, the company opened a vehicle factory that now builds SUVs. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

Last year, GM and a partner company began transforming yet more farmland to build an Ultium Cells battery cell factory next door in Delta Township. Michigan awarded $120 million in public incentives. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

The closure of the old plants has meant lost jobs and revenue for Lansing and Lansing Township. “We're left with the contamination and the state is giving money to other areas,” said Lansing Township Supervisor Maggie Sanders, right. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

Delta Township resident Nicole Leitch, pictured here with her husband Jason, said the blight GM left behind in Lansing makes her skeptical of the company’s assertions that its new Ultium plant won’t pollute her community. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

Flint feels abandoned

In Flint, entire neighborhoods disappeared after GM pulled up the stakes at its massive former Buick City complex, which once employed tens of thousands. Flint City Council member Quincy Murphy drives through his childhood neighborhood, which is now dominated by vacant houses and empty lots. (Bridge photo by Kelly House)

GM left the property so contaminated, it has taken $31 million and counting to clean up — all of it covered by taxpayers. Twenty-four years after GM closed the factory, a developer has finally come forward. But only after state and local taxpayers ponied up tens of millions more to defray the developer’s cost to build on GM’s rubble. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

Other communities worry too

In communities with more recent factory closures, an information vacuum about potential contamination leaves residents to wonder whether they’ll be next to inherit the industry’s mess.

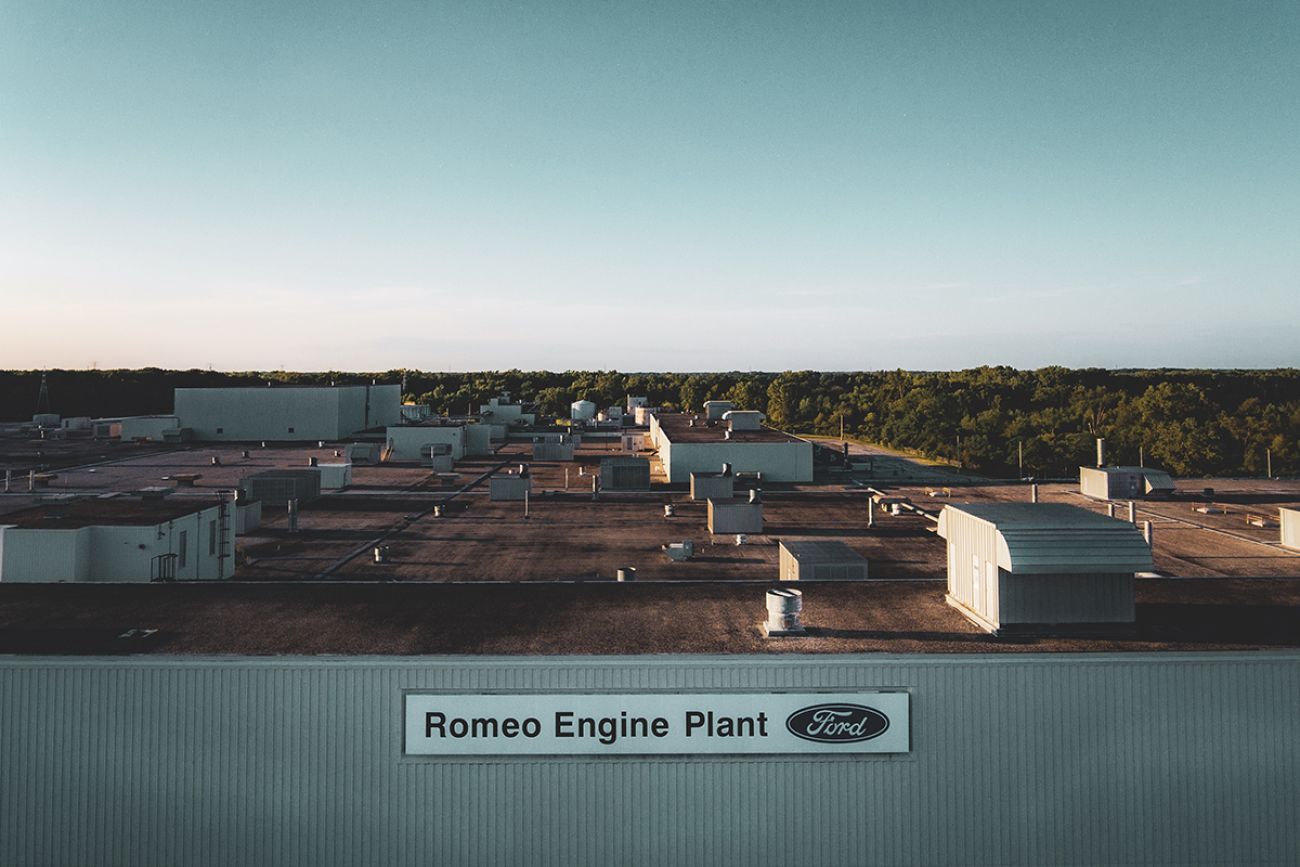

Ford Motor Co. closed its 2.2 million square-foot engine plant near Romeo in December, leaving questions about the next use for the property — and what residue may be lingering in the soil or groundwater. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

Village President Meagan Poznanski said Romeo is eager to find a new life for the factory. But nobody knows when that might happen, “and that just makes you nervous.” (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

In the small city of Milan, south of Ann Arbor, Mayor Ed Kolar has struggled to get answers from Ford about the future of a plastics plant it closed a decade ago. Kolar said company reps demurred when he asked whether the property was contaminated. Bridge Michigan later obtained documents confirming his fears. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

While Milan struggles to recover from Ford’s exit, the company is building a new plant on rural land 80 miles to the west in Marshall, with the help of $2 billion in public subsidies. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

The wounds inflicted by automotive pollution extend deep into the industry’s supply chain. In Jackson, the public is paying to clean up hexchrome, volatile organic compounds and PFAS left behind by Michner Plating, a company that added shine to seat belt buckles for Michigan automakers. The work is so dirty, automakers stopped doing it in-house decades ago. (Courtesy U.S. EPA)

The polluted site can’t be redeveloped until cleanup is complete, making it a barrier to Jackson’s economic revival. For Karen Muse and Jeff Froelich, it’s also a health threat. Their home is equipped with a special system, pictured in the foreground, to keep toxic chemical vapors at bay. (Bridge photo by David Ruck)

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!