Michigan teen looks to college, but after pandemic she questions her drive

GRAND RAPIDS—The walls are painted green and blue in the room where Jackie Calderon spent about 22 hours a day during the first year of the pandemic. There is a wallpaper strip of the letters of the alphabet along the ceiling. The curtains are emblazoned with a happy zoo full of animals: a giraffe, a crocodile, a lion.

There is a crib for her baby brother. One dresser. A full-size bed, shared by Calderon and her mother.

Through most of the 2020-21 school year, Calderon seldom left that room in her Grand Rapids home except to eat or go to the bathroom. Grand Rapids Community Schools was fully remote because of the pandemic from March 2020 through January 2021, so Calderon attended classes online, lying on her bed or sitting on the floor.

Related:

- At Michigan State, graduation haunted by ‘what could have been’ without COVID

- Cheers for Dr. Fauci at comeback University of Michigan commencement

The high schooler, who’d fought bouts of depression in the past, fell into what she describes as the deepest depression of her life. At times she binge ate everything she could find, then didn’t eat for days. School work that she’d routinely completed ahead of deadlines before the pandemic sat unfinished.

Calderon calls that period her “hibernation.”

In some ways, Calderon, who graduated from C.A. Frost Environmental Science Academy Middle High School Tuesday, still hasn’t fully woken up.

In that green and blue room, the academically strong student began having trouble focusing on her studies — a problem that continued when students returned to classrooms.

“I guess I lost my work ethic,” Calderon said. “I hope it’ll get better when I go to college.”

This fall, colleges across Michigan will welcome the first class of freshmen for whom the majority of their high school experience was buffeted by a deadly virus and the measures put in place to try to keep them and their families safe. They lost the last two months of their sophomore years when Michigan closed every K-12 school in 2020; and since then, many lurched between online learning from home and socially-distanced classrooms with mandatory masking.

While COVID protocols have now been dropped and school routines have returned to normal, students like Calderon say they are still struggling to regain their footing.

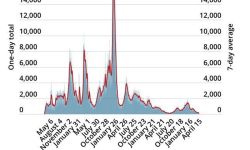

COVID-19 has killed more than 36,000 Michigan residents. Just one half of 1 percent of Michigan’s deaths were people ages 10-30, but the pandemic still left scars.

More students in early elementary grades than before the pandemic are suffering from speech and social-emotional deficits, with some needing to re-learn how to play together. On campuses, even with safety measures lifted, college students are less involved in activities, report more mental-health issues, and worry about lifelong relationships they may have missed while stuck in dorm rooms.

And for seniors like Calderon, for whom the majority of their high school experience was shaped by COVID-19, educators describe a lingering loss of focus they worry could follow them to college.

‘Out of the groove’

The pandemic took a toll on learning nationally, with standardized test scores indicating that students advanced less academically during the 2020-21 school year than during normal, pre-pandemic school years.

Particularly hard hit were minority students, with the learning gap between white students and their classmates of color growing, as well as students like Calderon who had more remote instruction.

Some college leaders around the country say students are arriving on campus less prepared, both academically and emotionally, after two years of learning disruptions.

Others aren’t arriving on campus at all — college enrollment is down across the country, including at most of Michigan’s public universities. A recent Bridge Michigan analysis of college enrollment data showed 54 percent of students from the high school class of 2021 enrolled in a two- or four-year college last fall, down from an average of 63 percent college enrollment in the three years preceding COVID-19.

There are early indications that the downward trend in college enrollment will continue this fall. The share of Michigan high school seniors filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) — the form that serves as a precursor to federal, state and institutional aid – dropped this school year. About 43.5 percent of Michigan students filled out a FAFSA form as of April 29, slightly below the nationwide rate of 47.1 percent, according to the National College Attainment Network’s FAFSA tracker. Last year at this same time, 44.8 percent of Michigan high seniors had filled out the FAFSA.

At Bay City Central High School, fewer students than usual committed to colleges to attend on “decision day,” May 1, than in past years, said Principal Andy Kowalczyk. “Our highly motivated seniors, the top 10, I don’t see a huge issue with them,” he said. “They’re still excited and turning in their scholarship (applications).”

But for others, the pandemic “got them out of the groove,” he said.

“What I see more than anything is the number of students that have depression and anxiety, the kids who aren’t coming to school. There might normally be one or two” in the 1,100-student school who are too depressed to come to class, Kowalczyk said. “Now, it’s at least 10 times that amount.”

Scores on Michigan’s standardized test, the M-STEP, declined across the board in 2021 compared to 2018-19, the last full pre-pandemic school year. Lower academic skills can discourage some high school grads from enrolling in college, and make college coursework more of a challenge.

Academic deficits were expected. Other problems have educators scrambling for answers.

Brad Lundvick, principal at Frost high school where Calderon is a senior, said students are struggling to focus on school work. Teachers have noticed a higher level of apathy than in pre-pandemic times.

“It’s a frame of mind that students are (struggling) to get back,” Lundvick said. “It’s creating anxiety. We’re encountering problems that we don’t know a solution to.”

Fresh start in college

Calderon always loved math. But in online classes in her bedroom, with many of her classmates turning their cameras off and kids bragging about cheating on tests and her world seemingly getting smaller by the day, geometry just didn’t seem to matter anymore.

Everyone in her household contracted COVID in December 2020. “We all were in our own rooms alone on Christmas,” Calderon said. Around the same time, a family friend got COVID and was in a coma for two months before recovering. One of her friends died in a house fire.

“I've always liked to have my control over things growing up,” Calderon said. “I was the one in charge at home because mom was always working. And then the pandemic struck and it was just like, how do I control this? And I couldn’t.

“I'd always have my friends I could talk to and I could come to school knowing that I could distract myself with something, but then it suddenly became like, ‘Oh, school is, like, not there anymore.’ And that caused my depression to become deeper than what it should have been.”

In late March, when she spoke to Bridge, Calderon said she was four chapters behind in reading a book for her English class. At night, she said she’d tell herself she needed to catch up, but then she’d put it off again.

“It’s a hard book to understand. I’ll just do it later.”

In April, Calderon hadn’t decided where she was going to college. She’d been accepted at Northern Michigan University, Western Michigan University and Detroit Mercy. She knows that wherever she goes, she’ll have to recapture that love of learning that COVID stole from her and some other 2022 graduates.

“I feel like maybe that mentality will slip off once I go into college,” she said. “I’m hoping it will slip off.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!