‘They destroyed our little town.’ What Michigan’s auto industry left behind

- As the auto industry builds its EV future, Michigan’s abandoned former factory towns are still stuck in its past

- Contamination often doesn’t come to light until after a plant closes

- Investigation and cleanup cost money and precious time as communities struggle to recover when a factory closes

MILAN—It’s been more than a decade since Ford Motor Co. stopped producing plastic car parts in this town of 6,000, and Mayor Ed Kolar has lost patience.

For years, the 1.3-million-square-foot factory has sat idle, providing few jobs and little tax revenue while Ford continued to use the site for storage.

Michigan’s industrial legacy

The latest on pollution in Michigan:

- Michigan ‘polluter pay’ bills coming, following Bridge auto industry probe

- Did auto industry pollute your Michigan town? Find out with interactive map

- Photos: See how auto companies left trail of pollution, toxins in Michigan

Repeating history:

- As automakers win incentives for EV plants, Michigan pays for polluted past

- With thousands of tainted sites, Michigan Dems eye return to ‘polluter pay’

- Key findings in Bridge Michigan auto project

The cost of bad policy:

- How Bridge tallied $259M in public costs for auto industry pollution

- Small supplier, big mess: Jackson pays the price of auto industry pollution

A new road:

Over the summer, businesses were scrambling for properties with easy access to highways and utilities amid a level of industrial growth that Michigan hasn’t seen in generations. Milan, though, was forced to sit on the sideline because its major industrial site remained in limbo.

“We’re stuck with business that wants to come here,” Kolar said, “and we have to say ‘No thank you,’ because we’re sitting on this dinosaur.”

The mayor said he worked his connections to secure a meeting with Ford. When they were face to face, he urged officials to either put the factory to better use or up for sale. The Ford people were polite but noncommittal as they explained roadblocks to a potential sale.

As they spoke, Kolar said, one of the Ford reps used the word “brownfield.”

Kolar was floored. Rumors had circulated in town that the plant, which produced fuel tanks and bumper fascia for 35 years, left contaminants. He asked one of the Ford reps: Are you confirming those rumors?

“She just said, ‘Well, we need to talk with Ford Land Division, that's all I can say.’”

As the auto industry races to build large manufacturing plants in the transition to electric vehicles, Milan is among more than a dozen Michigan towns still sitting on vacant sites automakers left behind. Redevelopment efforts are complicated by contaminants in soil or groundwater — some of it not previously made public, thanks to the state’s opaque cleanup laws.

Bridge talked to local leaders in three of those towns — Milan, south of Ann Arbor, Romeo, in Macomb County, and Wyoming in Kent County:

In Romeo, hope for fast turnaround

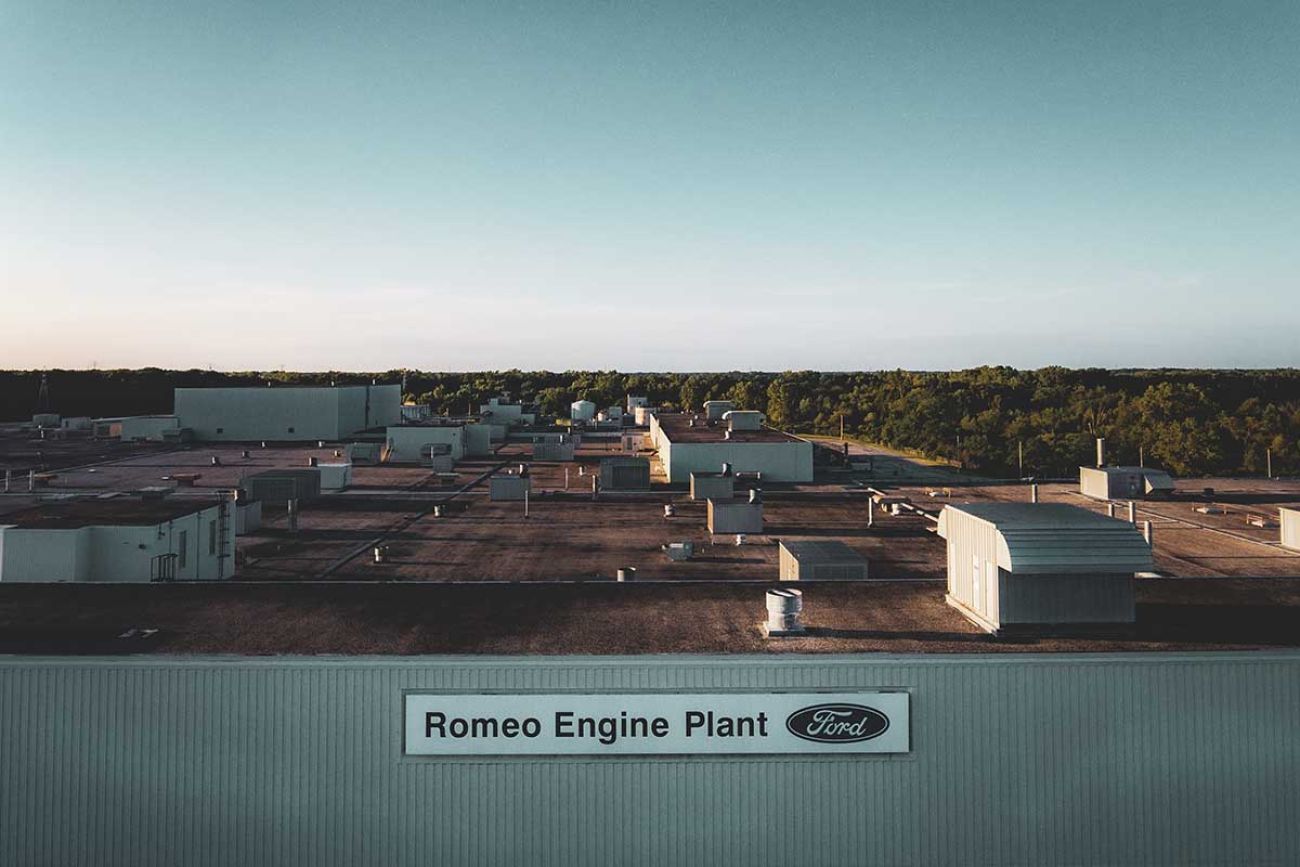

Village President Meagan Poznanski of Romeo sees the massive, vacant Ford factory every time she drives past it on M-53.

The 2.2-million-square-foot plant is where Ford built automotive engines for 30 years before it closed last December. She dreams that a new buyer will help replace the 600 factory jobs Ford moved to its other factories.

But nobody knows when that might happen, Poznanski said, “and that just makes you nervous.”

As in Milan, the town’s future hinges on Ford’s plans for the facility. The automaker told Macomb County officials last month it plans to sell the plant, but did not say when.

Ford said it must first decommission the factory. Next, possibly around the first of the year, it’s expected to start environmental testing to determine what’s needed to clean it up for reuse.

“They want to get the property into a reasonable state for them to begin marketing and promoting it,” Vicky Rowinsky, planning and economic director for Macomb County, told Bridge.

It can’t come soon enough for Romeo, or Macomb County. The auto industry accounts for $11.8 billion of county GDP, almost twice the amount of its next most-robust industry, aerospace and defense. With a national $1.2 trillion construction boom underway tied to EV investment, “we don’t want to lose these windows” of opportunity, Rowinsky said.

Ford did not reply to Bridge inquiries. State environmental records show the company removed five underground storage tanks from the site starting in 1988. A note in the file said the property carries deed restrictions. The records don’t make clear why, but such restrictions are commonly placed on properties to contain contamination that is impractical or too costly to remove.

More recently, state records show the company established 10 groundwater monitoring wells and took samples near the northwest corner of the factory. State data reviewed by Bridge does not indicate results.

Join us for live discussion Thursday on Michigan’s industrial legacy

On Thursday, Sept. 28 at 12 noon, Bridge Michigan business editor Paula Gardner and environment reporter Kelly House will discuss their industrial legacy reporting project. Senior editor David Zeman will moderate this interactive discussion. Bring your questions!

Current estimates place the timeline of Ford’s environmental work at six months. Any longer may complicate sale plans while the industrial market is still hot.

Rowinsky recalled that other factory redevelopments in Macomb County have ranged from a few years — like a former General Motors site in Warren — to decades, like a former Ford Visteon factory in Shelby Township that became an Amazon distribution center after Ford and the township settled clean-up litigation.

Rowinsky said Romeo received two calls in August from prospective buyers, which she said validated the village’s proactive push to ready the property for sale. Officials hope Ford shares that urgency. But Rowinsky notes, “there's not a for sale sign up just yet.”

Wyoming took control

For more than seven decades, workers in Wyoming transformed sheet metal into doors, hoods and other parts for GM vehicles at the company’s 36th Street metal stamping plant. The plant once employed as many as 3,000 people, running shifts around the clock, seven days a week.

“It provided a lot of families with a lot of income,” Wyoming city attorney Scott Smith said, “along with (the) benefits…auto jobs provided.”

But GM closed and discarded the plant in 2009 as it entered bankruptcy protection.

Wyoming, a suburb of Grand Rapids, quickly bought the property, with a real estate company as initial partner, and spent more than a decade marketing it.

Unlike Milan, Wyoming officials knew a cleanup was needed. Trichloroethylene, a degreasing solvent that can cause cancer and central nervous system damage, was found in the soil and groundwater in 1985.

But it was not until GM properties in Wyoming and elsewhere were abandoned in bankruptcy that the full scope of the environmental work became clear. The bankruptcy court created the Revitalizing Auto Communities Environmental Response (RACER) Trust, which was responsible for cleaning up the GM properties and positioning them for redevelopment.

In Wyoming, the public has so far spent $2.6 million on the cleanup job. And local officials were eager to play a role in finding a new employer to run a plant that had supplied manufacturing jobs to Wyoming since the Great Depression.

“We wanted to control what went there,” said Smith, the city attorney.

“Our worst fear,” he said, “was somebody would buy the plant, (not demolish it) and use it to store RVs and boats.”

The state signed off on RACER’s work to contain the contamination in 2018. Anyone using the property from here on out can be confident that risks have been identified, the city says.

Yet the large parcel lingers, despite its proximity to Grand Rapids, where industrial property is at a premium: Vacancy in the Grand Rapids market is just under 3 percent, while new construction — much of it for automotive uses — totalled almost 2 million square feet as of June, according to a report from Jones Lang LaSalle.

The property includes a rail line and industrial-grade power access, but “the longer it sits on the market, people start to have a (negative) perception,” said Nicole Hofert, Wyoming’s director of community and economic development.

Last year, the city sold the property to Chicago-based Franklin Partners, which took over marketing. The $5.25 million deal covered about $300,000 in city expenses over the years, and restored the property to the tax rolls.

It’s still waiting for a new manufacturer.

Milan waits

Ford twice announced plans to sell its plastics plant in Milan to auto suppliers — first Flex-N-Gate in 2006, then Inergy Automotive Systems in 2011. But the first deal fell through, and though Inergy occupied the Milan site for a short time, it never bought the property.

Kolar, the mayor, said he hasn’t heard anything more from Ford since his meeting in June. He suspects the company is holding onto the plant because “you’re going to have problems with the environmental side if you try to sell it.”

Through interviews with regulators and a review of state environmental records, Bridge found the site is contaminated with heavy metals, volatile organic compounds, and possibly PFAS.

Experts say that shouldn’t be a surprise. Many plants built before the late 1980s are likely contaminated. But the true extent often isn’t known until a site is sold or shut down, because state law often doesn’t require companies to keep regulators informed of pollution or cleanup plans.

The Milan plant was subject to additional scrutiny when it closed because it was a permitted hazardous waste facility.

Tests so far reveal soil and groundwater tainted with heavy metals and volatile organic compounds. A groundwater sample contained elevated PFAS, but EGLE geologist Nicole Sanabria said more tests are needed to validate those results.

“The data that we have so far doesn't show significant issues,” Sanabria said, noting the contaminants don’t appear to be migrating off-site or affecting drinking water.

But investigation continues into the possibility that trichloroethylene, the degreasing agent found in the soil, could vaporize into the indoor air. Ford may have to place some restrictions on future uses for the site if the property is sold, Sanabria said.

A Ford spokesperson would not answer questions about the company’s plans for the Milan site, but acknowledged that the company is conducting environmental monitoring.

While the company plots its next move, Milan struggles. Local tax collections from Ford are less than half of 2005 levels. The city water system, which Milan upgraded to accommodate Ford’s needs, now delivers a fraction of its enlarged capacity. Residents’ rates have risen to make up the difference.

When Ford won state incentives to build a new 2.3-million-square-foot EV battery plant in Marshall, 80 miles to the west, Kolar was outraged. The state pledged more than $2 billion in incentives, tax breaks and road improvements for the Marshall plant, which is expected to provide 2,500 jobs.

Ford and other automakers say they need larger tracts for EV plants, and rural land is easier to turn than industrial properties.

But the greenfield race toward EVs also comes with concerns about worsening sprawl in a population-stagnant state that struggles to maintain its ever-expanding inventory of roads, water pipes and power lines.

Kolar said the announced deal was a signal that Milan isn’t part of Ford’s future.

“Financially, they've destroyed our little town,” he said. “And as taxpayers are giving (more than) $1.6 billion for the new plant, our region is suffering from lack of employees, lack of tax base, lack of water and sewer use.

“Everything that no one wants to talk about anymore.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!