Dead deer and small fish: Michigan students learn to investigate poaching

- Northern Michigan University’s wildlife conservation law and policing program prepares students to become Michigan Department of Natural Resources officers — tasked with enforcing fish, game and natural resource laws

- Students learn the scientific study of ‘green crimes’ to better know why people violate protection laws and how to prevent them from doing so

- One NMU professor estimated that ‘a great number’ of poaching cases on state and federal land goes unreported

As a group of Northern Michigan University students huddled around the carcass of a northern pike supposedly caught earlier that day, they knew something was wrong: The fish was far too small.

Michigan law requires anglers to release northern pike if they’re less than 24 inches long in an attempt to protect fish before they mature and can reproduce.

The students approached a fisherman standing nearby, interviewed him and began matching evidence to a filed complaint to find out if he violated Michigan fishing regulations.

Before long, the students ascertained that the man had illegally harvested the northern pike.

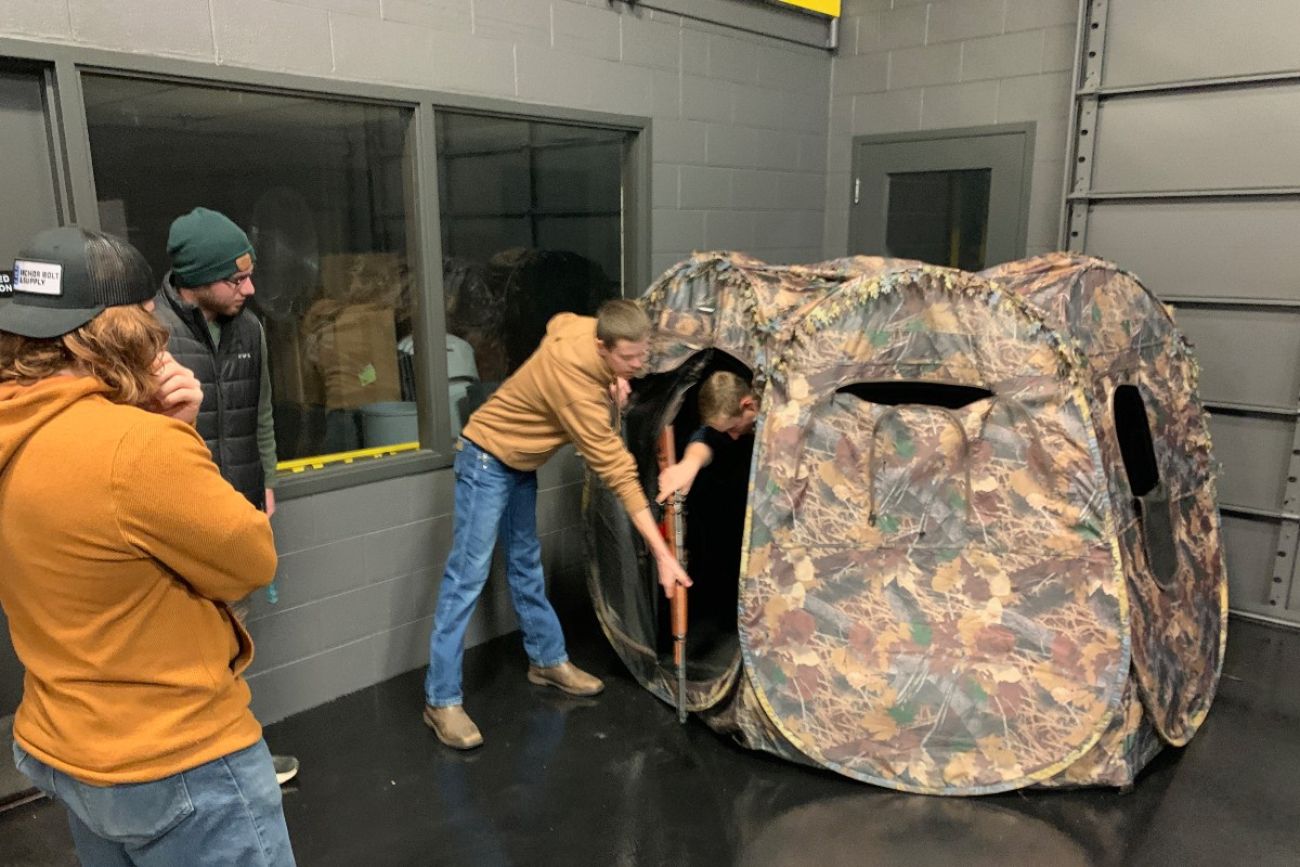

That is one of several scenarios students take on when they enroll in NMU’s wildlife conservation law and policing program.

RELATED:

- As GOP targets Michigan DNR, Ted Nugent blasts agency’s ‘insane’ regulations

- As inflation strains Michigan parks, DNR budgets, lawmakers weigh fee hikes

- Prosecutor won't charge hunter in southern Michigan wolf kill

For students hoping to become conservation officers for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources — tasked with enforcing fish, game and natural resource protection laws — the class gives a glimpse into their day-to-day work.

Jeremy Sergey, a conservation officer who teaches the class called Conservation Law Enforcement, said his goal is to immerse students in the lifestyle of conservation officers.

“I like to bring in a lot of recruits and show (students) what the training is like,” said Sergey, who has been an officer since 2016. “I might throw a couple of scenarios at them.”

Topics range from the history of state and federal wildlife conservation law enforcement to comparative discussions about wildlife rangers protecting endangered species in Africa and Asia.

Since Sergey began teaching in fall 2023, two students have gone on to graduate from the DNR’s 23-week conservation officer training academy.

Joseph Budnick is one of those students. He graduated from the academy in early July and will work in Mackinac County after field training with a veteran officer. Another former student, Olivia Haerr, graduated in the same cohort and is assigned to Baraga County.

After taking Sergey’s class, Budnick — who already had an interest in conservation work — knew “as soon as another academy was going to run, I was going to be applying for it.”

Much of the wildlife conservation policing program blossomed out of NMU criminal justice professor Greg Warchol’s research into illegal wildlife trading and poaching in Africa.

Warchol teaches Environmental Conservation Criminology, one of three classes all students enrolled in the program have to take before graduating with a minor in wildlife conservation law and policing.

Criminology is the scientific study of crime and borrows from fields such as sociology, psychology, economics and statistics to determine why people commit crimes and how to prevent them.

In his environment-focused class, Warchol said, students grapple with “what kind of person goes out and poaches wildlife in a national or state forest in Michigan or poaches animals in Africa and Asia.” Students also learn about what domestic law enforcement and their international counterparts do to combat those crimes.

While most of Warchol’s research is focused on environmental crimes — or “green crimes” — in Africa, he suspects illegal hunting is fairly common in the US. In 2024, the Michigan DNR generated more than 10,000 poaching complaints from 43,250 calls.

The average person doesn’t poach out of desperation, according to a 2020 Arizona State University report on illegal hunting on federal land. Rather, they’re often driven by potential profits, thrill or excitement and the “relatively low risk” associated with the crime.

Investigating environmental crimes comes with several disadvantages, Warchol said. Often, victims are wildlife or their surrounding environment and they can’t provide statements, the crimes are committed in remote parts of the forest and tips from the public are limited.

Warchol suspects that “a great number” of crimes in national and state parks likely go unreported, partly because there aren’t enough conservation officers to cover the vastness of DNR land. Roughly 250 conservation officers are spread across Michigan.

One solution besides increasing enforcement or militarizing conservation efforts — as is the case in some African countries — is to educate people on the value of wildlife.

“It’s a problem you’re never going to end, but it’s a problem you can control and reduce to a certain extent, because there’s always demand for wildlife products,” Warchol said.

Budnick, the conservation officer, said he took that job because he wanted to protect animate and inanimate natural resources that, without protection from the DNR, would be vulnerable to exploitation.

Sergey, the adjunct instructor and conservation officer, said he continues to reiterate his class with each new semester, finely tuning the curriculum to what students are interested in pursuing after school, whether it's working as conservation officers or as firefighters for the DNR.

“It’s a project, it’s in development,” Sergey said. “But I think it gets better and better every year.”

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!