Grand Rapids seeks to raise African-Americans’ stake in marijuana boom

In Michigan as elsewhere, black residents are far more likely than whites to be arrested for marijuana-related crimes, despite similar rates of use.

But once pot became legal in other states, the communities most affected by marijuana arrests often found themselves underrepresented in the competitive, lucrative industry selling it.

That’s a scenario the City of Grand Rapids is hoping to avoid.

Related: New rules to give residents of poor cities piece of Michigan pot industry

Grand Rapids has developed a program called the Marihuana Industry Voluntary Equitable Development Agreement (MIVEDA), which aims to give locals a better chance to receive a limited number of medical marijuana facility land use licenses.

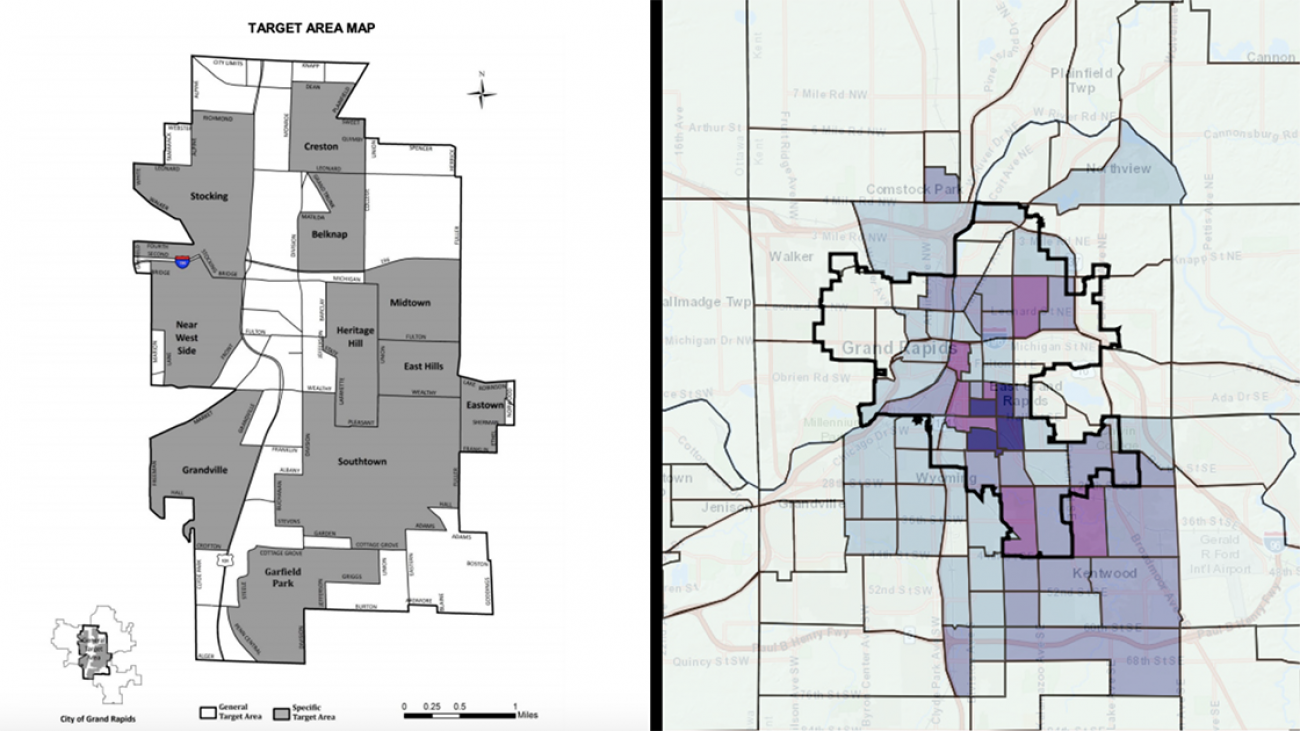

Because of a statewide ban on affirmative action, the city can’t give applicants a leg up based on race. Instead, the system gives preference to applicants from low- to middle-income neighborhoods in Grand Rapids, as defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development — areas that also happen to have more African American and Hispanic residents than other areas of the city.

“The question was: Could we do things to help correct past wrongs that happened to people of color in relation to marijuana?” said Landon Bartley, Grand Rapids’ Senior City Planner. “At the end of the day, I think it’s the closest that we’re going to get to hitting the goals that our city commission wanted.”

Whether Grand Rapids’ program will actually give these residents a better chance to enter the rapidly-evolving cannabis industry remains to be seen. Even locals who are supportive of the program’s intent question its ability to increase diversity among the people and businesses entering the industry — in part because the program doesn’t address significant financial barriers to obtaining an industry license.

“Could we do things to help correct past wrongs that happened to people of color in relation to marijuana?” ‒ Landon Bartley, Grand Rapids’ Senior City Planner

But the city’s efforts are indicative of a growing interest nationwide to do something to ensure communities most affected by marijuana’s criminal past have a stake in its future. It also shows the uphill climb would-be regulators face implementing policies as the cannabis industry barrels forward to profit.

A history of arrests

People of color have long been more likely to be arrested for marijuana crimes than white people, despite multiple studies showing similar usage rates. In Michigan, African-American residents are more than three times more likely to be arrested for marijuana crimes than white people; the disparity is similar at the national level.

Most marijuana arrests are for possession, which often entails carrying a small amount of pot intended for personal use. Reducing these minor arrests and the racial inequity that often comes with them are among the stated goals of groups pushing for marijuana legalization across the country. However, racial disparities persist even as arrest rates drop in states where marijuana has been legalized.

“When you start with the criminal element and then you never build those communities and those families back up, you get exactly what we have now,” said Shanita Penny, president of the Minority Cannabis Business Association, an advocacy organization supporting diversity in the U.S. marijuana industry. “These folks are still locked up at four times the rate of their peers.”

Given this history, social justice advocates decry how quickly whites have come to dominate the newly-legal industry. According to a survey by Marijuana Business Daily, 81 percent of cannabis business owners are white, despite making up just over 60 percent of the U.S. population. As states and cities work to shape regulations, the wealthiest voices in the industry are becoming the loudest in the room, Penny said.

If local governments want to write policy that helps people of color get into the industry, Penny said, they better get on it. “The window of opportunity in cannabis,” she said, “is small.”

The Grand Rapids solution

Recreational marijuana use became legal in Michigan last December. But like many Michigan cities and the state itself, Grand Rapids is just now beginning to grapple with medical marijuana, which has been legal since 2008. The state approved a new system for licensing commercial facilities in 2016 and began issuing licenses last July.

After the city commission voted to allow medical marijuana facilities last summer, officials knew they were likely to be the only city in this generally conservative region to open its doors to cannabis. Grand Rapids Planning Director Suzanne Schulz said city officials wanted to avoid becoming overrun with facilities and traffic, so they set about creating strict zoning requirements and separation distances for would-be pot shops.

Based on geographic restrictions, there will likely be around 35 dispensaries and five grow operations allowed in the city, said Bartley, the senior city planner. With an expected $700 million in medical sales statewide and eventually $1.5 billion in recreational, those spots are hot commodities.

The city will review applications for zoning approval through a lottery system; applicants had two weeks in March to submit for the first round. If applicants from lower-income neighborhoods choose to fill out the city’s MIVEDA form they’ll get bumped to the front of the line, assuming they also commit to the program’s other agreements. Those with the most points will get considered first when the city draws the lottery order on April 26.

Applicants can get added points for (among other things): being residents of Michigan or Kent County; agreeing to hire at least 15 percent of employees who live in Grand Rapids; working with other local businesses. Once signed, the MIVEDA is legally enforceable.

“Local government cannot make race-based decisions. Period,” said Schulz, the city planning director. “So even though we really want to encourage particularly African Americans who really had this disparate impact from enforcement … we can’t acknowledge that formally.”

Up against roadblocks

While local advocates laud the city’s attempt at equitable policy, they’re doubtful it will work.

“If history serves as any kind of indicator, it won’t have the effect that is intended,” said Jamiel Robinson, CEO of Grand Rapids Area Black Businesses, which advocates on behalf of African American-owned businesses in the city.

He said the MIVEDA requirements — which applicants can satisfy by proving that 25 percent of their ownership group lives in a qualifying area — aren’t ambitious enough.

“You don’t have a lot of African Americans, if any, to my knowledge, that have applied in this first round of applications,” Robinson said. “So if the policy isn’t helping to increase employment opportunities, increase wealth opportunities for African Americans, then to me the policy is flawed.”

One reason for that, Robinson said, is a cultural stigma around marijuana in the African American community. Growing up, kids are taught they will be punished to the greatest extent of the law if they’re caught using marijuana, he said.

“That’s the mindset you have to get around. There’s a lot of trauma there from being overly incarcerated,” Robinson said.

But possibly the biggest hurdle, according to Robinson and a half dozen other activists and public officials who spoke with Bridge, is money.

The state requires applicants for medical marijuana licenses to show they have hundreds of thousands of dollars on hand to operate a facility. The lowest requirement is $150,000 for a license that allows growers to cultivate up to 500 plants. The highest is $500,000 for the largest grow license, allowing for up to 1,500 plants. Applicants can “stack” these licenses for larger grows; for example, four of the largest licenses would allow a company to grow 6,000 plants and require them to have $2 million at their disposal.

State advocates for the capitalization requirements argue they’re necessary to ensure business owners have enough resources that they won’t be tempted to sell to or buy from the black market if they’re short on cash.

In Grand Rapids, where only a limited number of facilities can operate, the value of real estate in the approved zones has skyrocketed.

“Right when we saw the map (of approved zones) we thought real estate is going to double or triple in those areas and that’s what happened,” said Tami VandenBerg, co-founder of the West Michigan Cannabis Guild and an applicant for a Grand Rapids-area medical marijuana facility license. “Despite the best intentions of equity, it knocked it out of most people’s hands who don’t have the capital” to snap up properties as they seek licensing.

City officials acknowledge the challenge that could pose for African American and Hispanic communities.

“This is not easy to get into,” Bartley said. “There’s less likelihood that a person of color is going to have half a million dollars lying around than a white person. So the minimum capitalization requirements are going to have an impact on” how many people of color can afford to enter the industry.

Unlike other industries, starting a cannabis business requires investors to have money already in hand; aspiring business owners generally don’t have access to federal bank loans because marijuana remains illegal under federal law.

“The investor pool (in Grand Rapids) is very very thin or is extremely insular,” Robinson said.

What’s next for Michigan

The recreational marijuana law that passed in November requires the state to develop a plan to “promote and encourage participation” in the cannabis industry by communities “disproportionately impacted by marihuana prohibition and enforcement.” It also adds a more accessible microbusiness license, which allows for small scale cultivation and sale akin to microbreweries.

The state Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs has until Dec. 6 to form regulations and make applications available for recreational marijuana businesses. Andrew Brisbo, director of the Bureau of Marijuana Regulation, said the state’s policy will focus on helping minority owned businesses quality for licenses and supporting them once they’re approved.

However, another part of the recreational law says that only those businesses with medical licenses can receive recreational ones for the first two years.

That means newcomers without a medical license may not be considered until the end of 2021, by which time many activists fear it will be too late for business owners of color to get a significant foothold in the industry.

In the meantime, Brisbo said the state has no specific plan to implement a social equity policy for medical marijuana licensing — “the horse is kind of out of the barn with issuing licenses there already.” He suggested, however, the state may revisit that issue once recreational pot regulations are implemented.

The Republican-controlled state Legislature isn’t planning to make changes any time soon: “Marijuana business incentives are not something the Speaker is spending his time on,” Gideon D’Assandro, spokesman for Speaker of the House Lee Chatfield, told Bridge.

A coalition of groups with connections to the marijuana industry is shaping legislation which includes several law changes that could increase equity. One part would eliminate the state’s current “caregiver” system, which allows an individual to grow marijuana for up to six patients including themselves, and replace it with a less expensive license under state law.

Supporters say the change would allow caregivers to transition to the regulated market with lower costs than the current license types, allowing for a more diverse pool of business owners. However, the proposal faces a steep climb, requiring a supermajority vote in the Legislature to change citizen-initiated laws.

Another barrier for some entrepreneurs of color: People convicted of a drug felony within 10 years or a misdemeanor within five years are automatically disqualified from getting a medical marijuana facility license. That could change if the Legislature votes to amend the 2016 Medical Marihuana Facilities Licensing Act.

Diversity advocates also want the state to clear the records of people convicted of non-violent marijuana crimes — something Gov. Gretchen Whitmer promised to do on her first day as Governor-elect. She recently said “the process is now underway” to shape expungement legislation.

How others are tackling it

If Michigan advocates are looking for an equity model that works, Penny, of the Minority Cannabis Business Association, said they may come up short.

“I don’t think anyone has done this well as this point,” Penny said. “We are way far away from an ideal program in this country.”

Penny’s group has drafted a model ordinance for cities that includes tiered licenses with access to low-interest loans, demographic data-tracking requirements, requirements for businesses to give back to communities, drug crime expungement and more.

Kenneth Harris, CEO of the National Business League, a Detroit-based national group that advocates on behalf of black businesses, said the state shouldn’t add any capital requirements to the recreational pot law, while developing cannabis businesses in opportunity zones and implement concrete policies that benefit communities of color.

“Blind handshakes and promises don’t build trust, nor can they measured or held accountable,” Harris said.

Rodney Holcombe, an attorney at the Drug Policy Alliance, said states and cities that are serious about increasing equity in the industry must develop policy with community input and commit to finding the money to help people sustain businesses.

“We need to ensure that if we’re doing (equity policy) we’re doing it the right way, that it has teeth and that folks are actually benefiting,” he said.

“It would be really unfortunate for us to just sell dreams.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!