Parting gift for college grads: $25k in debt

Clark Eagling has $45,000 in student loans -- and he’s the lucky one in the family. His wife, Aimee Kessel, owes $90,000 for her undergraduate and graduate college education. The debt is so large that the couple may be collecting Social Security before they finish paying for college.

“We’ve both essentially said that we don’t plan on ever paying them off,” said Eagling, 30, ofRoyal Oak. "By accident of birth, we’re given this extra challenge.”

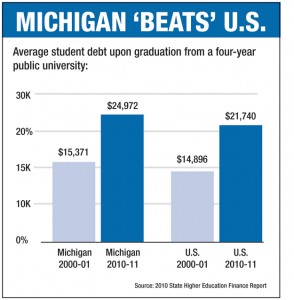

Eagling and Kessel were born and raised in Michigan and attended public universities here, where the net price of an education -- and the loans that come with it -- are higher than in almost any other state.

A Bridge Magazine analysis revealed that student loans at Michigan’s 15 public universities increased an incredible 49 percent in four years. From the 2007 to the 2010 academic year, the annual amount of loans taken out by college students jumped $600 million, reaching $1.8 billion at the state’s public universities in the 2009-10 academic year, the last year for which data is available from Michigan's House and Senate fiscal agencies.

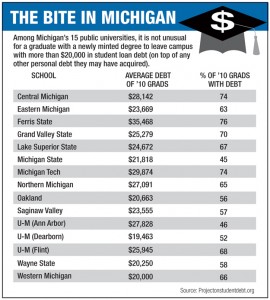

Campus-by-campus snapshot of student debt at Michigan’s 15 public universities

That $1.8 billion figure represents just one year’s worth of loans for current students, according to the state fiscal agencies. Extrapolating from national figures, if you add in loans taken out during the rest of the college careers of current students, plus outstanding debt from those who have graduated such as Eagling and Kessel, Michigan’s student loan total likely tops $30 billion -- the equivalent of more than 20 years’ worth of state appropriations for higher education.

That $1.8 billion figure represents just one year’s worth of loans for current students, according to the state fiscal agencies. Extrapolating from national figures, if you add in loans taken out during the rest of the college careers of current students, plus outstanding debt from those who have graduated such as Eagling and Kessel, Michigan’s student loan total likely tops $30 billion -- the equivalent of more than 20 years’ worth of state appropriations for higher education.

Many of those loans saddled students with interest rates much higher than current mortgage rates, making their burden even heavier in years to come.

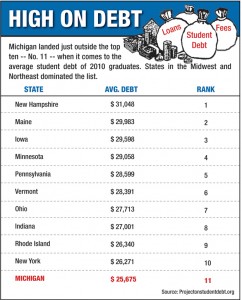

The average graduate with a bachelor’s degree left campus in 2010 with $25,675 in student loans, according to the Project on Student Debt. That’s the 11th highest student debt load in the country.

That growing debt is a drag not just on graduates' wallets, but on Michigan's fragile economy. Student loan debt often means students cannot afford to purchase homes or new cars; every dollar spent on student loans is a dollar not spent in the state’s private sector.

In 2010, for the first time, student loan debt nationally topped credit card debt, with the total expected to surpass $1 trillion in 2011.

Mark Kantrowitz, founder of FinAid.org., calls the explosion of student debt “unsustainable.”

“We’re seeing debt at graduation grow while (starting) salaries are not,” said “We’re approaching a point at which the debt becomes unaffordable.”

Universities dependent on loan dollars

Michigan families already pay more to send their children to state universities than families in almost any other state, according to a Bridge Magazine analysis. Michigan’s “college tax” of exploding student debt has materialized in concert with disinvestment in public funding for Michigan universities and tuition increases that have far outpaced inflation. As Eastern Michigan University President Sue Martin explains, as state budgets tightened, higher education was an easy place to cut because universities had the “safety valve” of tuition to make up for lost state funding. As state funding dropped, tuition rose.

Michigan families already pay more to send their children to state universities than families in almost any other state, according to a Bridge Magazine analysis. Michigan’s “college tax” of exploding student debt has materialized in concert with disinvestment in public funding for Michigan universities and tuition increases that have far outpaced inflation. As Eastern Michigan University President Sue Martin explains, as state budgets tightened, higher education was an easy place to cut because universities had the “safety valve” of tuition to make up for lost state funding. As state funding dropped, tuition rose.

And, of course, increased tuition and fees led to increased student loans.

In fact, student loans ($1.8 billion in 2010) now make up a larger percentage of Michigan public university budgets than state appropriations ($1.26 billion).

“If there weren’t any student loans, all the universities in the U.S. would fail,” Finaid's Kantrowitz said.

Bridge's analysis also found wide differences in the average loan debt of students at Michigan’s public universities. Ferris State University students graduated with the highest average student debt in 2010 ($35,468); Michigan Tech was next at $29,874; then Central Michigan, $28,142; and then the Universityof Michigan, $27,828.

Graduates of the University of Michigan-Dearborn in 2010 started their careers with the least debt ($19,463), followed by Oakland University, Wayne State and Western Michigan, all at about $20,000.

Debt rises as degrees fall

The surge in debt accepted in pursuit of degrees has not always led to a commensurate surge in degrees granted.

Four universities in Michigan (Western Michigan, Lake Superior State, U-M Dearborn and Saginaw Valley State) granted fewer degrees in 2010 than in 2007 -- even while total student loan debt on those campuses increased between 14 percent and 80 percent.

Among numerous possible explanations, those numbers may hint at increased challenges many students face in balancing studies with jobs needed to help pay for school.

Michigan State University economist Charles Ballard said he knows a student buried in loan debt who is “working 40 hours a week as a night watchman. Naturally, he’s having trouble staying awake in class.”

Students working more hours because of fears of mountainous school debt, and consequently faring worse in the classroom, is yet another ripple effect of lowered state funding, Ballard said.

“The MSU student body is stronger academically than it was 10 years ago, but yet we have this problem (of falling grades), Ballard said. “That’s not trivial.”

Loan debt at Lake Superior State Universityincreased 57 percent between 2007 and 2010, while the school awarded 23 percent fewer degrees. At the University of Michigan-Dearborn, total loan debt jumped 64 percent, while degrees dropped 11 percent.

"Declining state support and cuts to state financial aid programs have led to increased borrowing for many students," said LSSU's Thomas Pink. "and when they have to take time off to work and save more money, it takes a longer time for them to complete their degrees."

At Western Michigan University, the number of degrees granted dropped 11 percent because enrollment declined; the percentage of students completing a degree within six years has remained steady, said Cheryl Roland, executive director of university relations at WMU.

“As state funds have dwindled and the cost of higher education has shifted to students and their families, our students' debt load has increased,” Roland said. “That's simple math. While we work hard as a university to offset costs, it is impossible for us to replace lost state revenue without increasing tuition.”

Ken Kettenbeil of U-M Dearborn responded, "We do acknowledge tuition at Michigan's public universities has increased. This is a direct result of the reduction in state support. Specifically to U-M Dearborn, we strive to make a U-M Dearborn degree accessable to qualified students who can least afford it. Each year the university increases centrally awarded financial aid by at least the same percentage as tuition is increased."

Interest makes loans double-pricey

The student debt mountain is made even more treacherous by the interest rates attached to many student loans -- rates higher than what you find advertised now for mortgages and car loans.

You could nearly fill MSU's Spartan Stadium twice with the number of Michigan university students -- 147,389 -- who took out unsubsidized federal Stafford Loans in 2010. That’s 54,000 more unsubsidized Stafford Loan debtors at Michigan universities than in 2007. A commercial website, staffordloans.com, quotes a current rate of 6.8 percent on unsubsidized Stafford Loans. That’s 70 percent higher than current 30-year mortgage rates for home buyers with good credit. Student loans also are difficult to abandon; unlike credit card debt, student loans are almost never erased in a bankruptcy.

Kantrowitz says the rule of thumb on student loans is, by the time they are paid off, college grads will have paid double the amount they original borrowed, creating even more of a drag on the Michigan economy.

Extrapolating an estimate Kantrowitz makes for national student loan payments, Michigan college grads probably pay about $1.6 billion per year in student loan payments.

Extrapolating an estimate Kantrowitz makes for national student loan payments, Michigan college grads probably pay about $1.6 billion per year in student loan payments.

“Twenty years from now, there will be a cascading effect of this debt,” Kantrowitz said. “Parents won’t have saved for their children’s education because they will still be paying for their own. That will create an acceleration of a loss of affordability.”

In Royal Oak, Clark Eagling can’t help but imagine how his life would be different if he were born in another state. “I have family in Georgia, where if you have a B average (in high school), college is basically free,” Eagling said. “I understand what kind of fiscal shambles the state is in, but ... I feel like I’m being ripped off.”

Meanwhile, Eagling is back in school -- this time to try to become a teacher. While enrolled, payments on his existing $55,000 in student loans are put on hold.

“All I’m doing is delaying the inevitable,” Eagling said.

John Bebow contributed to this report.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!