The political tale behind the selling of Proposal 1

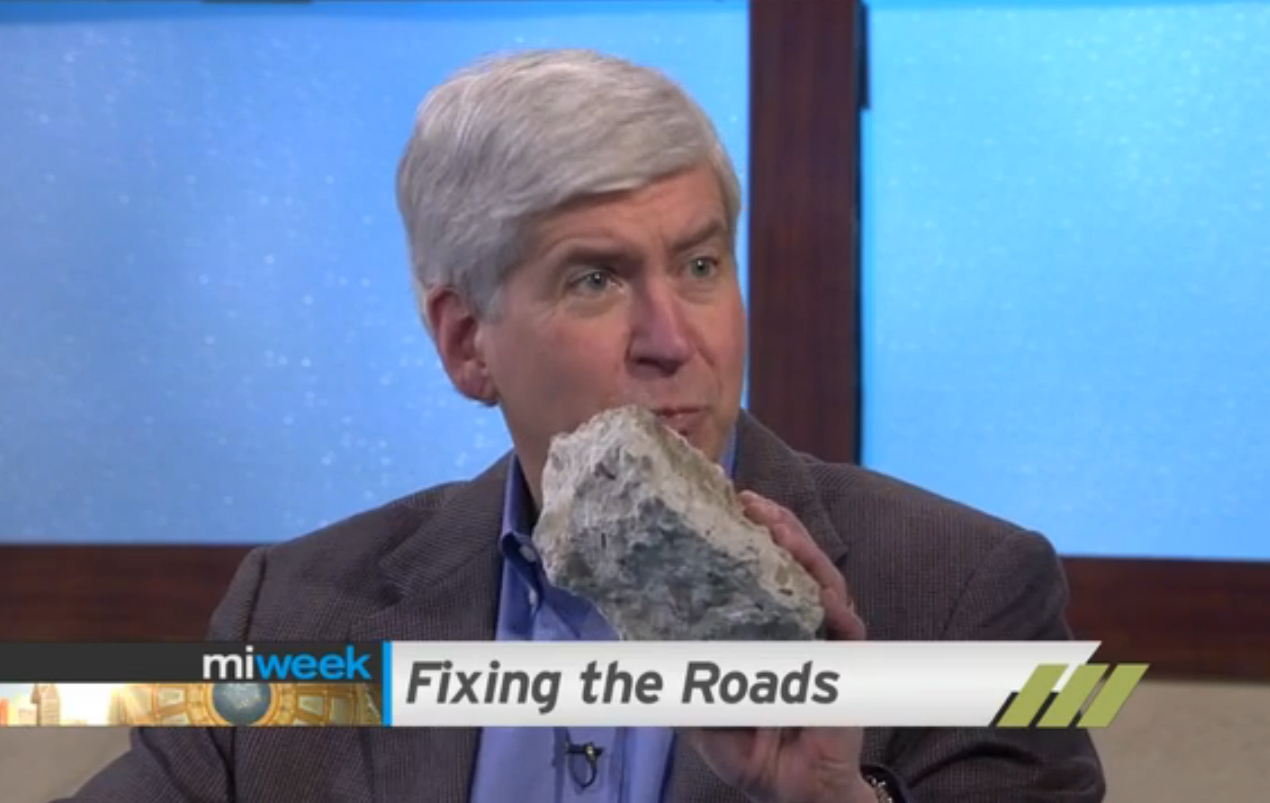

Gov. Rick Snyder is touring the state’s talk shows and editorial boards with a rock. Technically, it’s a piece of concrete, said to be broken from one of Michigan’s crumbling bridges. It’s a bomb, he says, telling a panel on “MiWeek” on Detroit Public Television, “You do not want this to end up in your vehicle.”

Randall Thompson is also touring the state, meeting mostly with tea party groups and others with foundational beliefs rooted in the idea that new taxes are, at the very least, a bad idea, and at worst, a threat to liberty. Thompson, executive director of the Coalition Against Higher Taxes and Special Interest Deals, presents Proposal 1 as 46,000-word, 10-bills-plus-a-constitutional-amendment monster stuffed with goodies that have nothing to do with roads. In other words, “everything (Michigan residents) hate about politicians.”

Both hope they have the winning hand as the battle to pass, or defeat, Michigan’s Proposal 1 moves into its final weeks.

How Proposal 1 became that piece of legislation is a case study in (depending on your point of view) either how politics is supposed to play out in a bipartisan spirit of compromise, or further proof that Lansing can’t do anything right.

More coverage: A Bridge primer: Untangling the pothole promise of Proposal 1

Who supports, and opposes, Proposal 1

Proposal 1, the legislature’s proposed solution to Michigan’s crisis of road-maintenance funding, is described by even its proponents as complex and by its detractors as a mess. Comprised of 10 bills and a constitutional amendment, it would raise $2.1 billion the first year, $1.3 for roads and debt relief on past road construction, plus $382 million for education and municipal revenue sharing, as well as more for mass transit, the state’s general fund and an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit. It’s these extras that have enraged detractors and are defended by its proponents.

To legislators involved in the December deal-making that gave birth to Proposal 1, adding extra funding for schools and local governments, while also increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit to soften the blow to lower-income families, was simply what it took for Republican leaders in Lansing to get the support they needed from Democrats. And, they add, it attempts to restore funding that was cut, sometimes brutally, after the Great Recession.

Rep. Marilyn Lane, D-Fraser, isn’t having the criticism. “It’s not the perfect pitch everyone would want,” she said. But, “this is the best deal we’re going to get.”

The problem, Lane and Democrats contend, is that the other party is so wedded to an anti-tax stance that it lacked the fortitude to vote directly to raise taxes, even when residents state they’re willing to pay more for improved roads. So the tax ended up being punted to voters to decide.

To Republicans, bipartisan accord on this package could only come with the crafting of a proposal that would appeal to lawmakers of both parties.

And observing the mashup that is Proposal 1 are the state’s voters, who in a chorus of website comments and social-media postings express a range of reactions, but appear to be anything but sold on the proposal, mostly faulting the legislature for the plan’s complexity and perceived excesses.

The sausage-making

“That’s being lazy,” Jase Bolger, the former Republican House Speaker who was an architect of the plan, said of the criticism, adding that many newspaper columnists and editorial boards have drawn the same conclusion. It isn’t political cowardice that pushed Proposal 1 onto the ballot, he said, but policy – the sales tax can’t be raised without a vote of the people.

“The legislature has already voted to raise the tax,” he said. “The public has to allow it to happen. This wasn’t a punt.”

Legislative observers will recall that late last year during the lame-duck session when the roads funding debate came to a head, Bolger presented a plan, roundly criticized by Democrats as both inadequate and injurious to education funding. It proposed to gradually raise the gas tax while reducing the sales tax and relying on annual growth to protect schools, which Grand Rapids Democrat Brandon Dillon dismissed it as “faith-based economics.” After the six-year phase-in period, opponents said, K-12 education could lose as much as $1 billion a year.

The Republican-led Senate had its own plan: a rising fuel tax, that would have roughly doubled the amount collected on gasoline over the course of several years.

Neither plan had the support of the governor, who wanted a higher fuel tax imposed at a time of historically low gasoline prices in order to quickly raise the $1.2 billion he said was needed to repair Michigan’s awful roads.

With no consensus, and Democrats cool on both plans, the far-more-complex machinery of Proposal 1 was hammered out in the final hours of the session.

Bolger, now out of office, is supporting it. “The bottom line is, this is a difficult problem with no easy solutions,” he said.

A challenge for the ad team

Difficult problems rarely have simple solutions, and the selling of Proposal 1 has leaned mostly on one simple idea: Safety.

Safe Roads Yes is the coalition in support, and as of February 10 its major contributors were road-building interests, according to Rich Robinson of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network. Advertising so far has been limited to mailers and a few videos, from proponents and opponents.

Robert Kolt plans to vote for the proposal, but after a lifetime in advertising, much of it political, has no envy for his colleagues who have to sell it.

“My experience over decades is, with a ballot proposal, you start at 60/40 no, unless they get a persuadable case for change,” said Kolt, who teaches advertising and public relations at Michigan State University. He contends that “most voters have made up their minds,” and the challenge will be to reach undecided voters with just the right pitch at just the right time.

With such a complex issue, opponents are finding it easy to “attack the atmosphere of politics and failure,” he said. If he were campaigning against Proposal 1, he would “call it a failure of leadership. ‘Send Lansing a message: We won’t play partisan games. (We) need a real fix for a real problem.’”

For boosters, he said, “maybe the advertising message needs to change (to): ‘You won’t get a second chance. If (road repair) is not done now, it’ll only get more expensive.’

“‘It’s all we got.’ There’s the pitch.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Gov. Rick Snyder has been carrying a prop around the state in his campaign for Proposal 1 – a piece of concrete from a crumbling Michigan bridge. (Screen capture from MiWeek, Detroit Public Television)

Gov. Rick Snyder has been carrying a prop around the state in his campaign for Proposal 1 – a piece of concrete from a crumbling Michigan bridge. (Screen capture from MiWeek, Detroit Public Television)