Extraordinary surgery in Michigan gives mom, daughters new faces

DETROIT — After a lifetime of disability, deformity, and — at times — the ridicule of strangers, Cherry Gayle is a woman of few words.

But in song, her voice is deep and clear, riding a warm breeze outside the Midtown Detroit Ronald McDonald House.

“What more do you want Him to do to prove that He loves you?” Gayle sings, an echo of the 46-year-old’s church choir, some 1,700 miles away.

Gayle and her two daughters, who live in Spanish Town, Jamaica, have been staying in Michigan since last fall, as they heal from extraordinary surgeries in which surgeons literally reshaped their skulls and rearranged their faces that had been misshapen by a rare genetic condition.

“I thank God,” Gayle says over and over. “By grace of God, I give thanks.”

Her brother, Richard Donovan Gayle, who traveled with her and her daughters from their hometown in Jamaica, smiles: “She does that a lot now — thanks God. We all do.”

Over the past 10 months, as the world seemed to lurch from one nightmare to another, Gayle and her daughters experienced something more akin to a marvel, through a team of doctors at Beaumont Royal Oak, and a surgeon whose love of art helps him resculpt flesh and bone.

Each has Crouzen syndrome, a rare genetic disorder which causes skull bones to fuse prematurely. Crouzen syndrome is believed to occur in about 1 in 16 million newborns, according to the National Institutes of Health. This "craniosynostosis" most commonly leads to eyes that bulge so dramatically that the eyelids can’t close, even during sleep. Crouzon also can cause eyes that point in different directions, a beaked nose and an underdeveloped upper jaw.

Because the eyelids can’t close over bulging eyes, they can dry out and develop scar tissue, leading to blindness. Deformed ear canals can cause hearing loss. There are dental problems, too, including cleft palate in some cases.

With access to health care, a patient’s skull is repaired early — usually before kindergarten, said Dr. Kongkrit Chaiyasate, craniofacial and microvascular surgeon at Beaumont Royal Oak. Over the past months, he led the team that would repair the skulls of Gayle, who had begun to go blind and would get a cornea transplant as well, and her two daughters, Mary Brown, 10, and Maria Davidson, 18.

“It is probably one of the most difficult surgeries in the craniofacial world because of the high risk. We are working around the eyes and brains, so it requires great precision,” he said.

‘None of this was easy’

The journey from Spanish Town to Michigan began in 2016 when a friend handed a newspaper clipping to Jamaica's Yvonne Campbell, who founded the Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome Education Foundation of Jamaica/Caribbean. The small, volunteer group connects those with facial deformities to medical providers willing to provide pro bono care.

Gayle has no independent source of income and relies on family, including her brother, Richard Gayle, who sells donuts and accompanied the family to Detroit. In Jamaica, Gayle and her daughters live in a simple, one-room home.

It took more than three years to put together the entire trip. Campbell had to persuade local doctors to see the family and document that Gayle and her daughters needed more medical intervention than they could provide. Campbell also reached out to a doctor friend in New York who, in turn, connected with Beaumont’s Chaiyasate. Through the Chaiyasate Craniofacial Fund, he and other other surgeons, anesthesiologists, pediatric specialists and opthamologists donate their time and the fund covers facility fees, medications, and other costs, Chaiyasate said.

Local media had picked up the family’s quest and local fundraising and funds from Campbell’s foundation funds covered travel costs.

“This is a family that lives on the margins,” Campbell said. “This is a society that is class-conscious ... They have limited health care. None of this was easy.”

Gayle and her daughters left home Aug. 31, touching down at Detroit Metro Airport.

With a temporary home at the Ronald McDonald House in Detroit, Gayle and her daughters underwent a series of surgeries stretching from September to March.

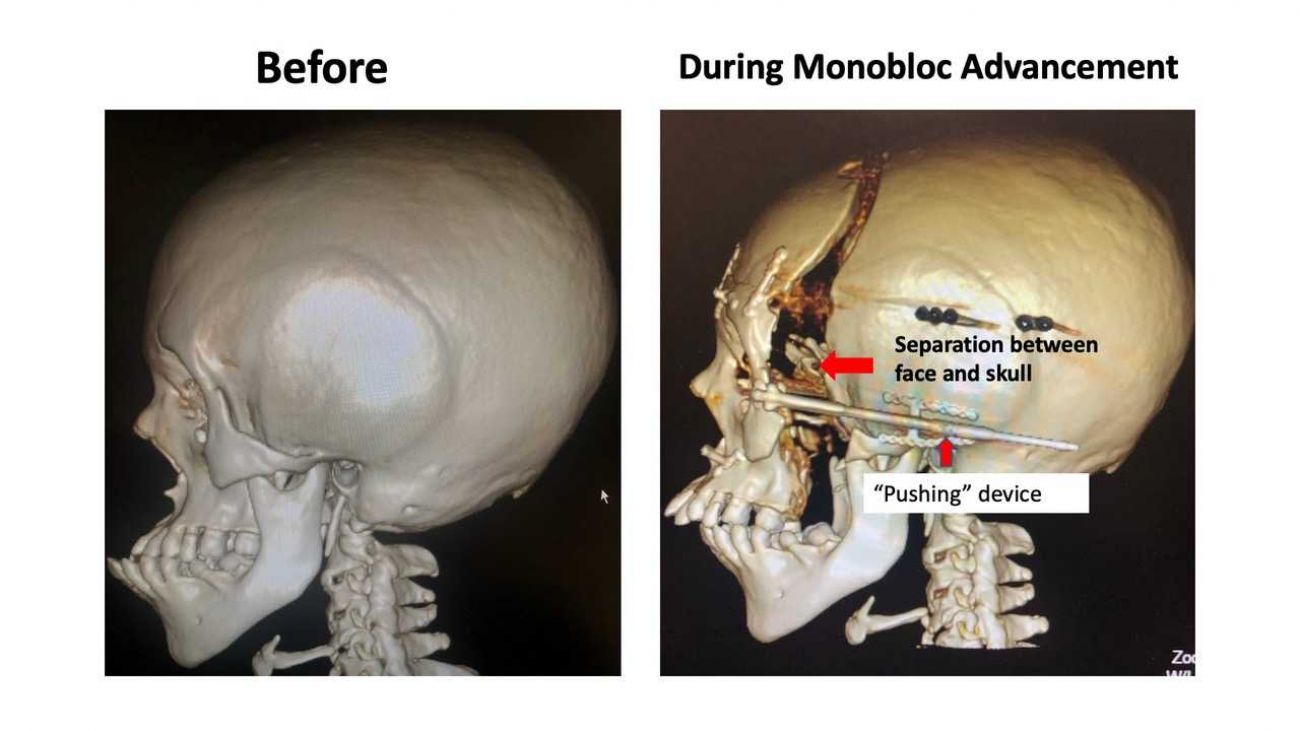

In those procedures, surgeons essentially pulled back the face from the facial bones of their patient, cut the skull nearly in half from top to bottom, and inserted screws between the two pieces. The screws extended outside their skulls and skin and were mounted into large external titanium frames around their heads. For about a month, each screw was tightened each day, pushing the front part of the skull forward, millimeter by millimeter, incrementally enlarging the skull and allowing new bone growth in the crack between the pieces.

The framework was removed after a month for each of the family members, though the screws remained in place for another two months as the bones stabilized, said Chaiyasate. (Mary’s was removed on her birthday in January, and they celebrated the extra big day with chocolate cake and ice cream at Applebee’s.)

It’s difficult to say how often the procedure, known as a monobloc distraction surgery, is performed each year in the United States — “more than dozens, but less than thousands” of times, said Robert Shprintzen, founder of the Virtual Center for Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome, a nonprofit that connects craniofacial surgeons around the world.

The surgery has been refined over several decades, but it remains “extraordinary” in part because it involves exposing the brain so that the underlying dura mater, a protective layer of the brain, prompts new growth of bone, he said.

The monobloc procedure, he said, is “a real test of the surgeon.”

It’s even more uncommon among mature patients like Gayle, for whom the years have made their bones more brittle and less able to generate new growth.

For Detroit surgeon Chaiyasate, that test of surgical skills is aided by a love of art, particularly anime. Chaiyasate used to be scolded by his teachers for doodling in the margins of his school work as a young boy in Thailand, he said, chuckling. He doodled in medical school and he doodles with his four children. And in the operating room, he’ll grab a marker and — on the disposable blue surgical drapes — sketch out for younger surgeons the procedure ahead.

The symmetry of the face has artistic harmony, he said, but its intricate inner workings more importantly allow us to take for granted our senses and ability to even breathe.

“To be a good surgeon you have to visualize your final product,” he said.

But to do it with no pay? To take on cases from around the world? There are no complicated or profound answers, he said: “I want to help people, and I can. It’s really that simple.”

And he’s quick to point out he wasn’t alone. Pediatric specialists, a neurosurgeon, anesthesiologists and others all donated their time. Their fees easily would have topped $50,000 for each of the three patients, Chaiyasate said.

For Gayle and her girls, the efforts of Chaiyasate and fellow surgeons allowed their eyes to recede back into their eye sockets so that the girls do not go blind.

Having lived with Crouzon for so many years, Gayle had already lost vision in her left eye. On March 6, Dr. Chirag Gupta, a Beaumont ophthalmologist and cornea specialist, replaced Gayle’s cornea with a donor cornea during a two-hour surgery, restoring her vision, although she still needs glasses.

A new life

It is an uncertain future that awaits when they return to Jamaica next month. Campbell has been trying to find someone to fix the roof at the family’s home, and make sure they have a doctor who will continue to care for them. It will not be easy, she said, but she is hopeful.

“They were in a terrible situation where they were going to go blind. They are less vulnerable now,” Campbell said.

Last week, 10-year-old Mary was dribbling a bright new Pistons basketball outside to the Ronald McDonald House courtyard. Mary had quit a local dance group before she left home. “I see the other children laughing at me,” she said. “I will go back now and dance and sing and live happily ever after.”

Nearby in the courtyard was 18-year-old Maria, who will try to return to her studies when she returns to Jamaica, something she’d abandoned because of bullying, according to her uncle.

The surgeries “will change things,” Richard Gayle said. “They look different now. People will no longer look at them and laugh.”

Maria sat quietly on a bench with her mother, the mid-morning sun warm on her new face, her mother singing softly.

Sinner man, can you see that Jesus loves you, yes, He do ...

If you only keep your faith, I know my God will see me through. What more do you want Him to do?

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!