Climate Change Report: As Michigan warms, cotton instead of cherry and grape crops? Bass instead of trout? Big rains and less snow?

If scientists are right, summer in Michigan by the end of this century will feel like that of a distant state. Think northern Arkansas.

A report on climate change by the Union of Concerned Scientists foresees 30 to 50 days a year in Detroit with temperatures above 90 degrees. Days of extreme heat – over 97 degrees – could increase fivefold. Incidents of extreme storms and flooding will rise, the report predicts. Lake levels will drop. Wetlands will shrink.

That report foresees shifts in Michigan climate that would disrupt ecosystems, raise the cost of Great Lakes shipping, threaten infrastructure, hurt tourism, spread disease and alter agriculture. The predictions parallel other analysis that takes note of rising atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that traps heat and was measured earlier this year at a level not registered in millions of years. Similarly, a white paper prepared for the U.S. Global Change Research Program foresees a 7-to-8-degree rise in summer temperatures in the Midwest by the end of the century. And a global report commissioned by the World Bank projects extreme heat waves, more violent storms, rising sea levels and disruptions to agriculture by the end of century absent significant reduction in carbon dioxide emissions. The U.S. Department of Energy forecasts disruptions to the nation's energy section, including interruption of rail and barge traffic, coastal damage to oil and gas facilities and damage to electrical systems because of more frequent storms.

“We are loading the dice toward the probability that we will see more of this,” said Jeff Andresen, state climatologist and assistant professor of geography at Michigan State University.

Andresen points to 2012, when Michigan cherry farmers endured the worst tart cherry crop in history, as one of many indicators change is already upon us.

Record-breaking warmth in March – 14 degrees above average - caused cherry trees to bud nearly six weeks ahead of normal. When temperatures dropped below freezing in April and May, more than 90 percent of the crop was destroyed. A similar sequence destroyed most of the cherry crop in 2002 as well.

“Twenty years ago if you would have asked me, I would have said that is weather, not climate. I don't think I can say that today,” Andresen said.

Milder winters might mean decreased deaths associated with cold and snow. But extreme summer temperatures are hazardous, especially to isolated elderly residents in poor urban neighborhoods. The Chicago heat wave of 1995 killed approximately 750 people.

The spread of tick-and-mosquito-borne diseases like Lyme disease and West Nile virus likely would accelerate if the climate warms. Experts also say waterborne infectious parasitic diseases like cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis would become more common with intense rains linked to climate change.

Heavy rains in Milwaukee in 1993 caused a sewage release that exposed some 400,000 people to cryptosporidium, a parasite transmitted in fecal matter that is resistant to chlorine. At least 54 people died. On Ohio's South Bass Island in 2004, more than a thousand residents and tourists suffered gastrointestinal illness linked to contaminated groundwater and months of above-average rains.

“When I look at our threats – aging infrastructure, increased population and increased precipitation - I am worried that we are reaching a higher level of likelihood that we are going to have more of these outbreak events,” said Joan Rose, a water quality expert who holds the Homer Nowlin Chair in Water Research at Michigan State University.

A 2001 study by Rose and several other researchers found that 51 percent of U.S. waterborne disease outbreaks between 1948 and 1994 were linked to heavy rainfall.

Invasive plant species like Phragmites, which choke out native wetlands, are advancing thanks to all-time record low lake levels on Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. The lakes have been below the long-term average 14 consecutive years.

Low lake levels threaten the $34 billion Great Lakes shipping industry, forcing freighters to carry lighter loads to compensate for shallower harbors and passageways. In March, Gov. Rick Snyder signed an emergency bill to fund $20.9 million in dredging for recreational bays and harbors.

If predictions of more intense storms and increased flooding prove true, municipalities may be forced to invest more in water-and-sewer infrastructure to prevent rising waste discharges. All-time record rains in Grand Rapids in April triggered discharge of 429 million gallons of partially-treated sewage into the river.

Warmer waters would mean decreased habitat for cold-water species like brook trout and walleye and increased habitat for warm-water species like bass. A heat wave in 2012 killed hundreds of northern pike unable to tolerate temperatures in several Michigan rivers reported as high as 90 degrees.

It could be a similar story in agriculture. Warmer days spell a longer growing season, which could be good for crops like wheat, corn and soybeans. But crops like cherries and grapes could become a real gamble, with bumper crops one year and a bust the next.

An expert on Michigan agriculture said farmers are already adjusting to climate change – whether they call it that or not - by planting earlier and purchasing large machinery so they can get in and out of fields in spring more quickly to avoid wet conditions. They are investing more in irrigation equipment to counter hot and dry summer spells.

"They see a lot of these changes already,” said Phil Robertson, a researcher at the Michigan State University's W.K. Kellogg Biological Station.

Robertson isn't sure how fruit growers will fare by the end of the century, if climate models are correct.

“Do they grow cherries in Arkansas? I don't think so. We might be seeing cotton.”

All that heat could add playing days and profit for golf courses. Perhaps private campgrounds would benefit with a longer season. But businesses that rely on cold and snow for activities like ice fishing, snowmobiling and cross-country skiing - could be in real trouble.

A group created in 2007 by then-Gov. Jennifer Granholm, the Michigan Climate Action Council, in 2009 issued a series of recommendations aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, including increased energy efficiency, conservation and greater use of alternative energy sources.

A spokesman for Gov. Rick Snyder said the administration is convinced climate change is real.

“People may not agree about why climate change is happening, but it is certainly affecting Michigan,” said Deputy Press Secretary Ken Silfven.

Silfven said the administration is seeking to balance the needs of rural development with water quality and ecological health.

“Climate change will make Michigan’s water resources all the more valuable and we need to be ready.”

An expert on adaptation to climate change said Michigan will have no choice but to adjust.

“The word resilience is getting a ton of play now in the climate community and the planning community,” said David Bidwell, program manager for the University of Michigan's Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments.

“To base our planning for the future based on what happened in the past is a poor way to go.”

Climatologist Andresen offered a sobering lesson from the past.

About a thousand years ago, Vikings settled in Greenland at a time when the climate was favorable to agriculture. But with dramatic cooling that accompanied a climate shift known as the Little Ice Age, the Vikings failed to adapt.

“They perished,” Andresen said.

Ted Roelofs worked for the Grand Rapids Press for 30 years, where he covered everything from politics to social services to military affairs. He has earned numerous awards, including for work in Albania during the 1999 Kosovo refugee crisis.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

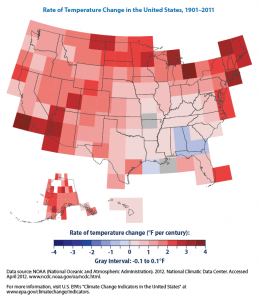

click to enlarge

click to enlarge