Smartest kids: Teaching starts early, with special focus on the poor, in Minnesota

Editor’s note: This is the second installment of Bridge’s series, “The smartest kids in the nation,” chronicling how four high-performing or fast-improving states are making gains in education while Michigan remains muddled in mediocrity. We previously looked at dramatic improvements in Tennessee, which has shot past Michigan in key subjects in recent years. Today we visit Minnesota.

ST PAUL, Minnesota – Julie Blaha brushes through photos on her cell phone of the middle school math classroom where she’ll teach this fall in suburban St. Paul. There is a photo of a bulletin board she’s given a fresh coat of paint. She stops at a photo of tiny, colorful cubes. “Look at all the centimeter cubes I have!” she said. “I’ve never had so many centimeter cubes.”

“It’s nerdy,” Blaha said, “but it’s exciting.”

Nerd is the norm in Minnesota, the state with some of the best math students in the nation. Minnesota fourth-graders were No. 1 in the country in math on the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress, the gold-standard test for cross-state comparisons. The state’s eighth-graders were tied for fourth. Minnesota students also are in the top 10 in reading in 4th and 8th grade, making it one of the leading education states, with students performing as well on some standardized tests as students in international darling Finland.

By contrast, Michigan students are at or below the national average in 4th grade reading and math and 8th grade reading and math – sometimes far below. Not only are Michigan’s scores lower, but they are rising slower than Minnesota’s, widening the education gap between the two states.

Why are students in Blaha’s classroom in suburban St. Paul learning more than students in the average Michigan school?

Bridge visited Minnesota and three other states to look for answers: Massachusetts which, like Minnesota, is acclaimed for its high-achieving students; and Tennessee and Florida, where academic achievement was similar or worse than Michigan a decade ago, but which have since produced stunning growth in student learning.

Better economy, better schools

Comparing the economies of Minnesota and Michigan is sobering. Minnesota’s unemployment rate was 4.5 percent in July, tied for ninth best in the country; Michigan’s unemployment rate was 7.7 percent, tied for 47th and dead last among Midwestern states.

Minnesota’s per-capita income is $46,227; Michigan, $37,497. In Minnesota, 11.4 percent of residents live below the poverty line, compared to 17.4 percent here.

Minnesota also outguns Michigan in education. Minnesota is second in the nation (to Massachusetts) in the percentage of adults with at least an associate’s degree, at 47.7 percent; Michigan’s college attainment level is 37.4 percent, below the national average of 39 percent.

From the outside, Minnesota and Michigan K-12 programs look similar. Both have many small school districts in rural areas and a few urban districts with high concentrations of poverty. Both state school systems have fiercely guarded histories of local control, and both have heavily unionized teaching forces. Minnesota is the birthplace of charter schools, and Michigan is a leading state in the percentage of students enrolled in charter schools.

So why is there such a wide difference in student achievement? Minnesota has a higher median household income, but all demographic groups – rich, poor, white and minority – perform better on the NAEP than their Michigan peers. One breathtaking example: Minnesota students eligible for free and reduced lunch rank fourth in the nation in fourth-grade math scores; Michigan students rank 48th.

While no individual policy is likely to account for the wide gap, Minnesota has embraced several reforms that could be tried here. Those reforms start at birth with the nation’s most extensive early childhood and new parent program, continue into the classroom with tough, consistent academic standards, and are wrapped in a funding policy that intentionally spends more on poor kids than rich kids.

Developed from birth

Kids enter the public school system early in Minnesota, sometimes before they have their first birthday.

The state’s Early Childhood Family Education program offers once-a-week classes to children ages 0-4 and their parents. It’s the parent component that makes the program unique. Now in its 40th year, ECFE helps teach parents to be their children’s first teacher.

There isn’t a close comparison in Michigan, or any other state for that matter. The Michigan Great Start Readiness Program offers classes for low- and moderate-income 4-year-olds to help kick start their schooling. The Minnesota program, by contrast, is open to all families regardless of income (with a sliding fee); parents can choose when to enroll, from the time their child is born until they enter kindergarten.

The program is wildly popular, with most families signing up when their child is 2 or 3. About one in five preschool children and their parents enrolled in the program last year, with a majority of Minnesota families taking classes at some point before their kids reach kindergarten.

Rich and poor are equally likely to sign up for classes (47 percent with household income below $50,000 and 53 percent above). “We have parents with advanced degrees and parents with no formal education,” said Jill Chisholm, an Early Childhood Family Education teacher in St. Paul. “If you’re from Ethiopia, you don’t know how to prepare your children for U.S. kindergarten, but they know their children need a lot of education to be successful. They want to help prepare them for school.”

Family fees (which pay for about 6 percent of the program) are kept low to encourage enrollment. A family earning $40,000 a year pays $50 for a semester of classes; a family earning $100,000 pays $225.

Chisholm and other instructors are licensed teachers, with certifications in early childhood and parent education (a special degree and certification rare outside of Minnesota). In some districts, such as St. Paul, instructors are paid on the same scale as elementary teachers; in other districts, instructors are paid by the hour.

Classes are offered in every school district in the state. In St. Paul, one of the state’s largest districts, there are ECFE classes specially designed for Somali immigrants, adoptive parents, LGBT families and divorced dads.

Don Sysyn, who runs the ECFE program in St. Paul, says the program is the key to Minnesota’s surprising academic record. “Parents are engaged in the program,” Sysyn said. “They realize how important being engaged with their children is.”

The classes are particularly important to parents, who learn ways to interact with their children to stimulate learning. “There’s a joint play time with children and parents,” Sysyn said. “The teachers model behavior. We try to use materials that everyone has in their homes.”

Later in the class, children and parents to go separate rooms, and parents talk about issues they face at home, from tantrums to discipline to how to find time to read to their kids.

The program is supported primarily by the state, which pays districts $120 per eligible child to hold classes. At $26 million in state funding, it’s a great investment for the state, argues state Sen. Charles Wiger, chair of the Minnesota Senate Education Committee, who represents a district that includes St. Paul.

“I’ve been championing it because of the great return on investment,” said Wiger, whose senate district includes St. Paul. “If a kid is ready for school, they’re less likely to need remediation or special education, and they’re more likely to (attain) third-grade reading proficiency” on schedule. “It helps graduation rates, and that helps college attainment and better jobs.”

There haven’t been long-term studies measuring the impact of the program on academic progress. But the program has survived potential budget cuts under governors ranging from progressive Democrat Mark Dayton to conservative Republican Tim Pawlenty, to former pro wrestler and Independent Jesse Ventura.

“By and large, we’ve had strong bipartisan support for early learning,” Wiger said. “The business community has been a strong supporter.”

Another key to its survival is the fact that ECFE is designed for all families, not just those with a low income. Business, community and political leaders see it as a service for everyone, not a handout to the poor. Many legislators have participated in the program with their children – or as children themselves. “If this had been targeted, it would have been cut long ago,” Sysyn said.

Instead of being cut, the Early Childhood Family Education program got a $4.65 million increase in its budget this year. “I can assure you, as education (committee) chair, it will get continued attention next year,” Wiger said.

More money for low-income schools

Despite Minnesota’s reputation as a high-tax state, its academic success can’t necessarily be attributed to money - total spending per K-12 pupil is virtually identical to Michigan ($10,855 per pupil in Michigan in 2012; $10,796 in Minnesota, according to the Annual Survey of School System Finances by the U.S. Census Bureau.)

What Minnesota does, though, is give a bigger slice of education funding to low-income schools.

Minnesota’s funding formula increases per-pupil funding as a school’s concentration of students eligible for free and reduced lunch goes up. (The full description begins on page 20 of this analysis of Minnesota school funding.)

For example, Red Lake Elementary, a school of 478 students in rural northern Minnesota, received $2,241 per pupil in extra funding in 2012 because 78 percent of its students qualified for free or reduced lunch. That same year, East Duluth High School, where fewer than one in five students are low income, received $102 per pupil in extra funding.

“Where we have the greatest need, we have the smallest classes,” said math teacher Blaha. “We get extra funding for concentrations of poverty, and that’s the right choice. If I have twice as many students in poverty, I’ll have four times as many challenges teaching. It’s not linear, it’s exponential.

“I’m willing to have a larger class in the suburbs so someone in north Minneapolis has a smaller class.” said Blaha, who teaches at Jackson Middle School in Anoka-Hennepin School District, a wealthy suburb of St. Paul and the state’s largest district.

Michigan’s per pupil foundation allowance doesn’t give extra state money to low-income schools. Most schools receive the same per-pupil allotment. About 50 historically higher-spending school districts in the state are allowed to tax their local property owners for additional funding. Most of them are affluent districts.

Michigan does provide $309 million in state cash for schools with high concentrations of at-risk students, many of whom are poor.

But that money is not enough to allow high-poverty Michigan schools to offer the kind of additional staffing that is offered in Minnesota, said David Campbell, superintendent of the Kalamazoo Regional Educational Service Agency.

“We don’t do a cookie-cutter approach to funding,” said Minnesota state Sen. Wiger. “We recognize the needs of low-income students in trying to close the achievement gap.”

That extra funding can be seen in Bel Air Elementary School, nestled in a working class neighborhood of otherwise suburban New Brighton, outside Minneapolis. The school has about 775 students in kindergarten through fifth grade, with some students bused in from a homeless shelter. About 42 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced lunch.

“Our compensatory budget (the extra state money for schools with high poverty) is bigger than the whole district where I used to work,” said Principal Dawn Weigand. “It allows us to hire support staff. All the support staff are licensed teachers, working full-time, many with specialty certificates like reading specialist.”

The students have homerooms, but are broken into smaller groups for reading and math, often with several support staff. In a school of 26 classrooms with homeroom teachers, there are six additional instructional teachers that float between classes, two full-time English as a Second Language teachers and a social worker.

“We feel so lucky to be here,” said Gretchen Zalewski, a third-grade intervention teacher at Bel Air. During a visit by Bridge, Zalewski and two other intervention teachers were working with about 20 students on reading.

“If I have twice as many students in poverty, I’ll have four times as many challenges teaching. It’s not linear, it’s exponential. I’m willing to have a larger class in the suburbs so someone in north Minneapolis has a smaller class.” – Suburban math teacher Julie Blaha explaining why she supports sending more money to schools with low-income students

By not being an official classroom teacher, “I can devote more of my energy to their needs,” Zalewski said. “It’s the key to everything, to have enough people and time to address individual needs.”

High academic standards

Minnesota adopted the reading standards of the Common Core State Standards (adopted by more than 40 states, Common Core is a set of concepts and skills that students are expected to learn at each grade level). But Minnesota did not adopt the math standards, because the state’s math standards were already higher than Common Core.

One example: all students take linear algebra in eighth grade, a course that is typically taken by ninth graders in Michigan.

“What we have are firm standards and clarity of standards,” said Dan Hoverman, superintendent of Mounds View School District, which includes Bel Air Elementary. “Whether you agree or disagree, it’s there. No one goes rogue here.

“What that’s done,” Hoverman said, “is given a clear direction.”

That makes a big difference in the classroom. “Early in my career (in the early 2000s) they were flipping standards a lot,” said math teacher Blaha. “In my first six years, I had four different text books. After that it stabilized.

“When you’re flipping standards, you have to spend time on what you’re teaching, instead of spending time on how to teach,” Blaha said. “When you have consistent standards, you’re able to look at scores and say, ‘Here are the areas we are struggling with, let’s get together and figure it out.’

“It’s exciting, great nerdy stuff, instead of ‘what do we have to teach this year?’”

NEXT: Florida rises from the depths

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

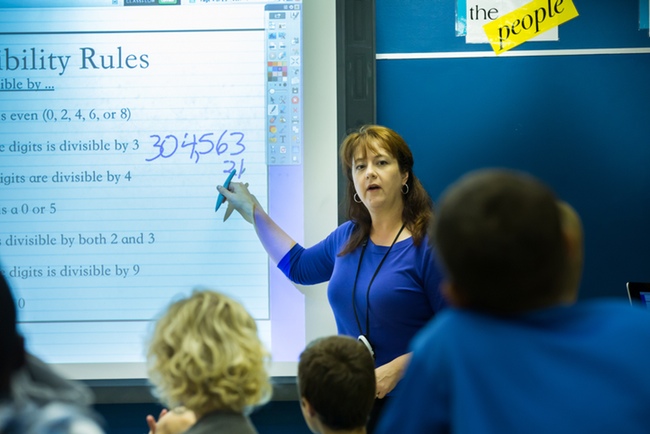

Julie Blaha is a middle school math teacher in Minnesota, which leads the nation in fourth-grade math achievement. Minnesota’s math standards are higher than Common Core standards. (Bridge photo by Stephanie Rau)

Julie Blaha is a middle school math teacher in Minnesota, which leads the nation in fourth-grade math achievement. Minnesota’s math standards are higher than Common Core standards. (Bridge photo by Stephanie Rau) Gretchen Zalewski, a third-grade intervention teacher at Bel Air Elementary in New Brighton, Minn., works on reading skills with two students. Minnesota provides more funding to high-poverty schools than schools with more affluent students, allowing low-income schools to hire intervention teachers. “It’s the key to everything, to have enough people and time to address individual needs,” Zalewski said. (Bridge photo by Ron French)

Gretchen Zalewski, a third-grade intervention teacher at Bel Air Elementary in New Brighton, Minn., works on reading skills with two students. Minnesota provides more funding to high-poverty schools than schools with more affluent students, allowing low-income schools to hire intervention teachers. “It’s the key to everything, to have enough people and time to address individual needs,” Zalewski said. (Bridge photo by Ron French) Lenssa Mergerssa works with 2-year-old daughter Liya in an Early Childhood Family Education class in St. Paul, Minn. The classes, open to all Minnesota families, offer training for parents about age-appropriate play that helps children learn. The parent education component of the state policy is unique in the nation. (Bridge photo by Stephanie Rau)

Lenssa Mergerssa works with 2-year-old daughter Liya in an Early Childhood Family Education class in St. Paul, Minn. The classes, open to all Minnesota families, offer training for parents about age-appropriate play that helps children learn. The parent education component of the state policy is unique in the nation. (Bridge photo by Stephanie Rau)