Big township bank accounts draw concern, defense

We all know Michigan's local governments have been struggling because of a plunge in tax revenues caused by the Great Recession and the housing collapse, not to mention shrinking state revenue-sharing payments.

Or do we?

A controversial new study by Isabella County Administrator Tim Dolehanty claims there is, in fact, an “embarrassment of riches” at many local governmental units, mostly townships and villages.

The study raises prickly questions about the structure and financing of local governments at a time when the state is demanding that they operate more efficiently and at a lower cost, experts say.

“It’s a hot potato topic,” said Tom Ivacko, administrator of the University of Michigan’s Center for Local, State and Urban Policy.

Dolehanty examined the finances of all 1,856 local governmental units in the state “as an exercise in curiosity." He found that many have hefty savings.

“I started looking at fund balances and was astounded at what I was seeing,” he said.

“I started looking at fund balances and was astounded at what I was seeing,” he said.

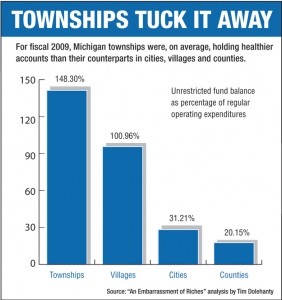

Dolehanty’s study, which focused on the 2009 fiscal year, found that townships were in the best shape of all local governments. They had, on average, an unrestricted fund balance equal to nearly 150 percent of their annual operational budgets.

Unrestricted fund balances are monies that are held in reserve, but are available to spend for a variety of uses.

Villages had an average unrestricted fund balance of 100.96 percent of annual operating funds in the year Dolehanty studied, while cities had an average balance of 31.21 percent. Counties’ average fund balances were 20.15 percent of annual expenditures.

The Government Finance Officers Association recommends local governments maintain an unrestricted fund balance equal to two months of operating costs, or 16.6 percent, according to Dolehanty’s study.

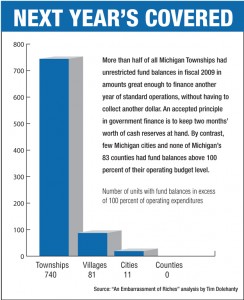

Nearly two-thirds of the state’s 1,240 townships have enough money in reserve to operate for more than a year without collecting any taxes or other revenues, he said.

Townships weather revenue storms

Villages, townships, cities and counties amassed $1.2 billion in unrestricted revenue, according to Dolehanty’s study. That has occurred as local governments saw property tax revenues fall by $900 million since 2007, according to a December Bridge analysis of Treasury Department data. (Much of that impact of that decline, however, occurred after the fiscal year Dolehanty studied.)

About 60 percent of all local government unrestricted fund balances were in township coffers in 2009.

But critics say Dolehanty’s study offers a misleading picture of local government finance, particularly for townships. Despite healthy looking averages, critics say there are wide disparities in financial pictures of local units. Some see Dolehanty’s study as a thinly veiled attempt to get additional revenue-sharing payments for counties, which his study showed have the lowest fund balance rates.

“It’s very, very frustrating to me. His methodology is just painfully flawed,” said Larry Merrill, executive director of the Michigan Townships Association.

One of Merrill’s biggest gripes involves what he says is the way Dolehanty calculated unrestricted fund balances using the various fiscal years of local governments.

Township fund balances appear inflated, Merrill said, because nearly 60 percent of townships collect property tax revenues at the beginning of their fiscal years and have yet to spent much of that money.

Cities collect their taxes in the summer when most are well into their fiscal years.

“He’s comparing two different units of government with vastly different cash flows,” Merrill said.

But even if that’s the case -- and Dolehanty is not conceding the point --adjusting for differences in fiscal years would still have left townships with a bulging $540 million in unrestricted fund balances, Dolehanty said.

Eric Lupher, director of local affairs at the nonprofit Citizens Research Council of Michigan, said townships and villages tend to have higher fund balances than cities or counties because of the way they fund large expenditures.

“Cities usually go to the bond market to borrow money for capital improvements,” he said. “Townships tend to save up the money for when they need to buy things. They’re making wise use of the taxpayers’ dollars.”

“Cities usually go to the bond market to borrow money for capital improvements,” he said. “Townships tend to save up the money for when they need to buy things. They’re making wise use of the taxpayers’ dollars.”

Do-it-yourself financing in Cooper Township

Such is the case in Cooper Charter Township in Kalamazoo County. Supervisor Jeffrey Sorensen said the township has used hundreds of thousands of dollars in its fund balance over the past few years to pay for a variety of expenses, including a fire truck, land for a cemetery expansion and a new roof for the township hall.

“If you don’t plan ahead and build a fund balance, you’d have to go to the voters for a millage request,” Sorensen said. “We don’t do that.”

While Cooper Township has been able to buy with its savings, the nearby city of Kalamazoo is shrinking its public safety staff. Declining revenues from property taxes and state revenue sharing resulted in a recent early retirement buyout of 221 city employees, including 54 public safety officers.

Cooper, with an annual budget of about $1.1 million, had an unrestricted fund balance of $1.6 million for its fiscal year ending March 31, 2011. The Kalamazoo City Commission on Jan. 3 adopted a 2012 budget of $159 million, down from $171 million in 2011. The city had only a $1.8 million general fund balance at the end of its fiscal year on Dec. 31, 2010.

“It’s easy to have a 100 percent fund balance when you aren’t providing services or doing such things as planning and zoning work,” said Dan Gilmartin, executive director of the Michigan Municipal League.

Providing police and fire services typically is about 50 percent of a city’s budget, but most townships “don’t spend a dime on public safety,” he said.

Cooper Township -- population 10,111 -- has a paid, nonunion, 26-member fire department. But the township relies on police protection from the Kalamazoo County Sheriff’s Office, which is supported by a countywide millage.

Merrill pointed to a 2010 survey by the Michigan Townships Association which found that 1,132 of the state's 1,240 townships operated their own fire departments, provided fire protection jointly with another jurisdiction or purchased fire protection from another local government. The survey also found that 319 townships provided or paid for police protection for residents.

Gilmartin, though, provided a document from the Treasury Department that shows 579 townships spent nothing on police services in 2010 and that an additional 262 townships spent under $10,000.

Merrill cited a number of other reasons why villages and townships generally are financially healthier than cities and counties.

Tax collections are rising in some rural townships because of a recent run-up in the value of agricultural property, he said.

Township employees, if there are any, tend to be paid less than city employees and are mostly not unionized.

“We have less legacy costs and fewer service contracts,” Merrill said. “For the most part, I think townships have controlled their spending pretty well in a declining revenue stream.”

Townships fear money grab by counties

Merrill said he is worried about the potential economic impact to the state caused by struggling cities surrounded by healthier townships.

“No unit of government is an island to itself,” he said. “Declining cities bring down the entire region.”

State emergency managers are running Benton Harbor, Flint and Pontiac. Detroit, which Dolehanty’s study showed had an unrestricted fund balance of negative $331.9 million in 2009, is trying to avoid a state takeover.

But Merrill said he views Dolehanty’s study as the first salvo in an attempt by counties to grab a larger share of tax dollars for services they provide to smaller local governmental units.

“His conclusion is the state should take money from townships and give it to counties,” Merrill said.

Dolehanty said his research is merely fodder for a needed public policy discussion on local government finances.

“I’m not under the illusion that this is going to change the structure of local government anytime soon,” he said. “But I think there are philosophical questions here that we should be asking ourselves.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!