Electoral College voting

The Michigan Legislature has set aside nine days to pass new laws before the end of the calendar year. Bridge has already outlined some of the issues likely to come up in this so-called lame-duck session or early in the next legislative session that begins in January. Today, we offer deeper looks at three measures that may be addressed before the New Year, starting with possible changes to electoral college voting. The other issues explored today are road funding and A-F school grades.

At issue

Michigan, like 47 other states, awards all its 16 electoral votes for president to the candidate who gets the most votes statewide. This doesn’t seem fair to some Republicans in Michigan, which has voted for the Democratic candidate for president every election since 1988. Term-limited state Rep. Pete Lund, R-Shelby Township, has introduced bills during the last two sessions that would change the way Michigan’s electoral votes are awarded to a system that almost certainly would be more favorable to Republican presidential candidates.

Under the plan expected to be introduced by Lund today, the winner-take-all method of awarding electoral votes would be scrapped for a method that would in virtually all elections split those votes. In the proposal, according to Ari Adler, director of communications for House Speaker Jase Bolger, the candidate getting the most votes statewide would be awarded a majority of the state's electoral votes - currently, that would mean at least a 9-7 split; Under the formula, for every 1.5 percent above 50.1 percent of the vote (counting only the votes cast for the top-two candidates), the winning candidate gets an additional electoral vote.

For example, in 2012, President Barack Obama won Michigan by 9 points over Romney, but instead of earning all 16 of the state's electoral votes, they would have been split 11-5. A candidate would have to win 61.6 percent of the cast ballots to get all 16 electoral votes - a whopping 24-point spread victory that would be highly unusual.

Here's how the electoral votes would be split:

The winner, even if by one vote: 9-7

The winner, with 52.6 percent of the vote: 10-6

The winner, with 54.1 percent of the vote: 11-5

The winner, with 55.6 percent of the vote: 12-4

The winner, with 57.1 percent of the vote: 13-3

The winner, with 58.6 percent of the vote: 14-2

The winner, with 60.1 percent of the vote: 15-1

The winner, with 61.6 percent of the vote: 16-0

Though Obama won Michigan by more than 400,000 votes, he would have earned only four more electoral votes than Romney.

What’s surprising is how much individual states can control who becomes president – not by how citizens vote, but by how state leaders decide to award electoral votes. By a simple vote of the legislature, states can award electoral votes by congressional district, by proportion of the overall vote, or just decide to award all the state’s electoral votes to the candidate of the Legislature’s choosing. (Florida considered doing this in 2000 in the contested contest between George Bush and Al Gore, before the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in.)

The politics

Lund said he’s pushing for Electoral College reform to make Michigan more relevant in presidential politics. “Right now, Michigan is meaningless in the electoral process along with 40 other states,” Lund said.

Lund said there was only one visit by one of the candidates for president or vice president to Michigan after the party conventions in 2012. He feels that if Michigan had a system that didn’t automatically give all its electoral votes to the overall winner – who the candidates pretty safely assume will be the Democrat ‒ then candidates would come to the state to fight for electoral votes that are up for grabs in individual districts.

“We need to come up with a system that brings candidates to the state,” Lund said.

Lund’s bill, though, may have the opposite effect. A winner-take-all election for 16 electoral votes is a coup for any candidate. By contrast, changing an electoral split from, say, 9-7 (a victory by 6 points or less) to 10.5-4.5 (a victory by 7 points) isn't a big deal.

While presidential candidates didn’t set up camp in Midland, they did spend a lot of money in the state. Matt Grossmann, associate professor of political science at Michigan State University, said Michigan had the 10th-highest level of campaign spending among the states during the 2012 presidential campaign.

Grossman said different electoral vote distribution policies have different advantages.

“If you reward all your delegates to one candidate, your state becomes a bigger prize,” Grossman said. “But if you allocate proportionality, you allow all parts of your state to be heard.”

But research out of the University of California at Berkeley suggests that Electoral College changes wouldn’t change the fact that presidential candidates spend the majority of their time in parts of the nation where voters tend to swing between political parties. Two states currently split their electoral votes – Nebraska and Maine – don’t get a lot of campaign stops.

If the proposed Electoral College changes aren’t likely to bring more candidates to events here, why is it being considered? Here’s why: In a close election, Michigan’s electoral votes being split 9-7 between the parties instead of 16-0 for the person garnering the most votes could swing the presidency.

“It’s very clearly a partisan effort to make the presidential election more conducive to Republicans,” Grossmann said. “I don’t think there’s any hiding of that.”

What we know

Republicans have large majorities in the state House and Senate, and Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, who just won reelection, is term limited so doesn’t have to worry about a possible voter backlash. Participants at a Michigan Republican Party Convention overwhelmingly supported the concept of splitting electoral votes in 2013.

Senate Majority Leader Randy Richardville, R-Monroe, acknowledges that the proposed change is about politics rather than improving the democratic process. He’s gone as far as to imply that the plan wouldn’t be considered if Republicans felt a Republican presidential candidate could win here.

“It seems political to me,” Richardville told MLive. “I have more confidence in our candidates maybe then some other people do. I think it’s more conservative to leave it the way it is.”

But Snyder, who before the election avoided answering whether he’d sign an Electoral College reform bill if it came to his desk, now says he is open to discussion.

“There’s two questions. One is, is it fair or not fair? Two other states do it (Nebraska and Maine). And you can talk about the theory, and the theory is, it could be fair,” Snyder told the Michigan Public Radio Network. “It’s more a timing question about when it would be appropriate. And that’s where I have real concerns.”

Snyder said he’d rather see the state consider the issue closer to 2020, when a new Census count would lead to Congressional districts being redrawn.

Likely outcome

Other states, including Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Virginia, have flirted with similar Electoral College shakeups, but all backed down under national attention. The lame duck session is unpredictable and bills move quickly. An Electoral College bill could be used as a bargaining chip to get more conservative Republicans to support other legislation, such as a larger state investment in road funding.

What’s at stake

If Electoral College votes are awarded by proportion of the overall vote, it would virtually assure that Republicans aren’t shut out as they have been since 1988. It would also likely make Michigan less of a player in presidential races because presidential candidates would have less reason to fight over a slight variation in an electoral vote split.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

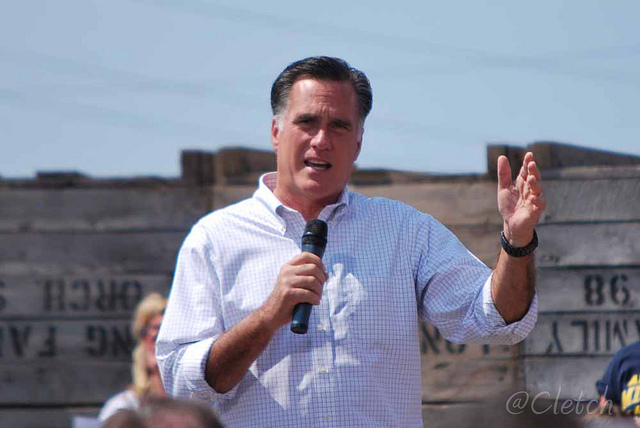

If Republicans had their way, 2012 GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney would have taken the bulk of Michigan’s 16 electoral votes even though he was beaten by roughly 450,000 votes in Michigan by President Barack Obama. (Photo by Flickr user Pat (Cletch) Williams; used under Creative Commons license)

If Republicans had their way, 2012 GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney would have taken the bulk of Michigan’s 16 electoral votes even though he was beaten by roughly 450,000 votes in Michigan by President Barack Obama. (Photo by Flickr user Pat (Cletch) Williams; used under Creative Commons license)