Breakthrough nears on mass transit tax in southeast Michigan

June 2018 update: Detroit regional mass transit plan dead for 2018

February 2018 update: As mass transit talks slow, will Wayne, Washtenaw counties go it alone?

The new year is bringing a renewed push to bring mass transit to southeast Michigan, following decades of disagreement that’s left the region with the worst public transportation system in the nation.

This month, elected leaders of Wayne, Oakland, Macomb counties and Detroit are expected to jointly announce recommendations that could result in a new plan for regional transit.

Among other proposals, local leaders want government officials to serve on the ten-member Regional Transit Authority of Southeast Michigan board and ensure that only communities served by the system would pay taxes for it, Bridge Magazine has learned.

The changes would require approval from the Legislature, but proponents say they still hope to place a tax request for the improvements on the November ballot.

The announcement, planned on or around Jan. 19, comes 14 months after voters rejected a $3 billion, 20-year tax for buses and trains. The breakthrough comes amid renewed concern about the importance of transit caused by the region’s public bid for Amazon’s $5 billion second headquarters.

The Seattle-based internet giant has said access to public transit will be a priority in determining where to build a second headquarters.

“The good news for the people who want to see a transportation system in southeast Michigan is we are making progress – significant progress,” said Oakland County Executive L. Brooks Patterson, who didn’t publicly support the 2016 regional transit plan.

Elected officials from the three counties and Detroit have met for several months about changes they want on the authority before they support a new transit ballot proposal. The chair of the Washtenaw County Commission also has been part the discussions since May 2017.

The RTA board is aware of the discussions and is optimistic elected leaders will help craft a new transit plan their residents will vote to approve, said Paul Hillegonds, chairman of its board.

“There needs to be ownership by the leadership and more direct engagement,” Hillegonds said. “The talks have been very constructive.”

Amazon effect

The decades-long battle over regional transit in southeast Michigan took on new importance when Detroit-area leaders last year crafted a bid in hopes of persuading Amazon to build its second headquarters in the area.

In fact, metro Detroit wants the Amazon headquarters - and the 50,000 jobs and $5 billion in local investments it will bring - more than any of the other cities making bids, a recent survey suggests. The city offered Amazon 30 years in tax incentives, according to a bid submitted to Amazon in October by a Detroit committee led by businessman Dan Gilbert.

Detroit’s Amazon bid cites plans by the SMART suburban bus line to add new express bus service on three major routes between suburbs and the city. And more services would be added within a year if Amazon moves to the region, according to the bid.

“Aware of how growth can lead to congestion, and committed to providing alternatives to people who don’t have a car or don’t want a car, regional leaders have initiated a series of investments in transit that are addressing existing shortcomings,” the bid proposal reads.

Southeast Michigan is the nation’s only metro area without rapid regional transit, according to Gov. Rick Snyder. The RTA’s transit plan from 2016 claims that an improved mass transit would lead to $6 billion in regional economic growth.

“We still have tremendous needs for transit. They (elected officials) need to stop squabbling over power and provide people with the transit they need,” said Megan Owens, executive director for Transportation Riders United advocacy group, which supported the 2016 RTA proposal.

Owens said she is concerned the leaders have met in private, but is optimistic.

“I’m cautiously trustful that we’ll still have a great transit plan.”

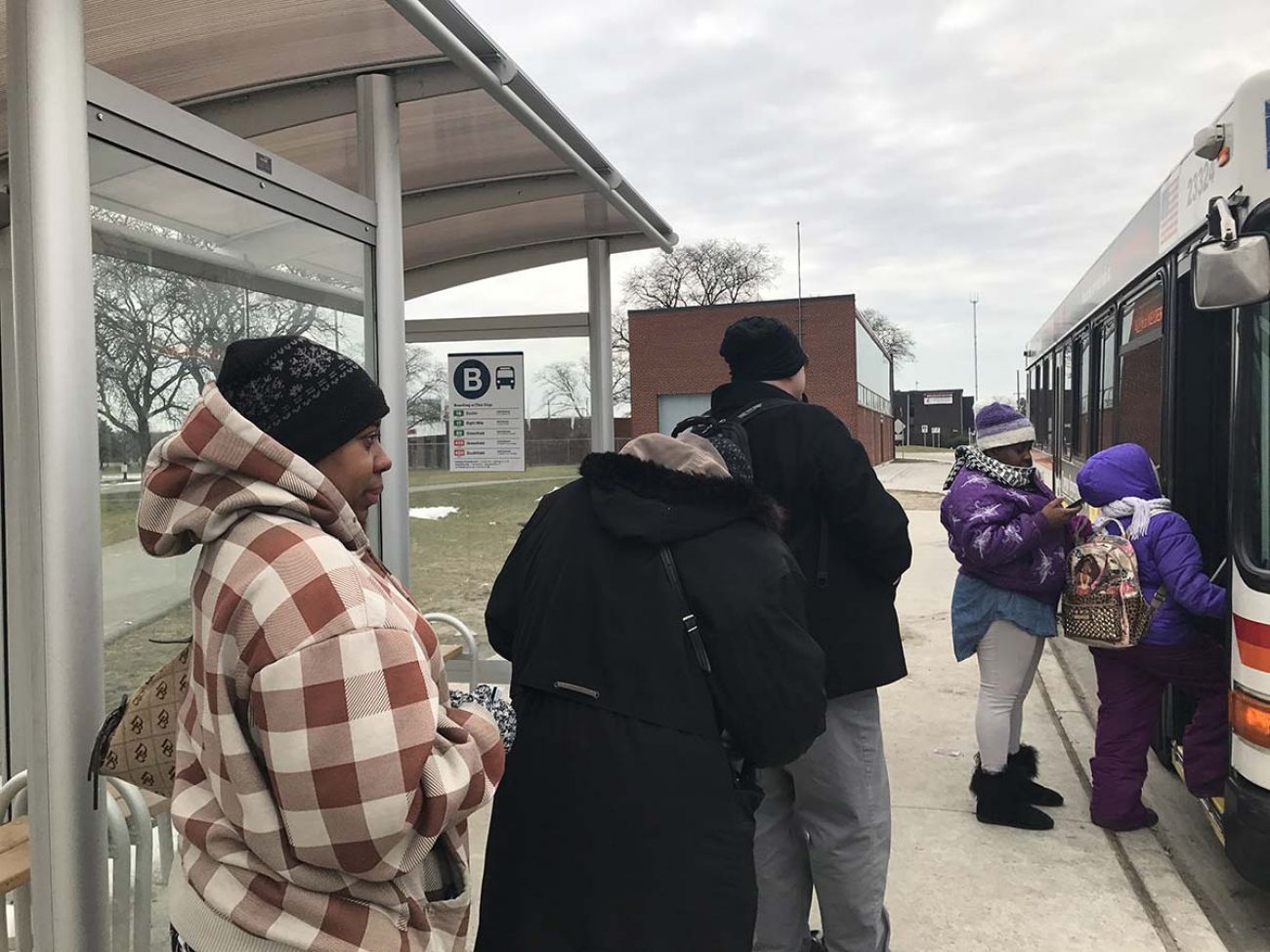

Last month, Tranese Franklin, 41, of Detroit stood at the bus stop at the abandoned Northland Mall in Southfield, one of the proposed sites for a new Amazon headquarters. She said her commute is proof that workers in the region need more and better transit.

It takes Franklin an hour and 45 minutes and three buses to travel less than 15 miles from her home in Detroit to work in Birmingham.

“They need to improve the timeliness and run (more) buses all night,” said Franklin, who would favor a tax to pay for new regional transit. “SMART is OK, but DOT (Detroit Department of Transportation) needs work.”

The state Legislature created the RTA in 2012 to coordinate regional public transportation in hopes of reviving the economy and attracting jobs to the region.

Currently, the three county executives and chair of the Washtenaw county commissioners each appoint two board members, and the Detroit mayor makes one appointment. The governor appoints a non-voting board member.

By law, local county and city employees or elected officials are not allowed to serve on the RTA board.

The current structure has been the topic of discussion because elected leaders want more say on the RTA board.

Andy LaBarre, chair of the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners, explained the two sides of the debate.

“If you have RTA board members directly (reporting to) a county official, it can be seen as making it overly political,” he said. “Another way to look at it is ... there’s a level of incentive for that elected official to be vested in the outcomes.”

RELATED: There’s a lot riding on Detroit’s new QLINE streetcar

The RTA’s master plan proposed joining bus systems in southeast Michigan by connecting Detroit’s city bus service and SMART suburban bus line to Ann Arbor’s transit service; and, eventually linking to the QLINE streetcar that opened last year on Woodward Avenue in Detroit.

A 2016 tax to pay for the vision revealed stark divides within the region: 53 percent of non-Detroit Wayne County residents opposed it, while 64 percent of Detroiters favored the measure.

Overall, the 1.2-mill tax lost by the narrowest of margins: 1 percent or about 18,000 out of 1.7 million votes.

Lee Howard, 25, of Detroit, predicts another transit ballot measure would fail. Last month, Howard’s Detroit bus showed up late and made him miss a connecting SMART bus at Northland Mall, so he had to wait more than 30 minutes in freezing temperatures for the next bus.

He ticked off a list of reasons a taxpayer such as himself won’t vote for it: the city’s bribery scandals and bankruptcy make people loathe to trust the money will be spent wisely; and there’s no guarantee more money will improve the system’s bad reputation.

“The money will be wasted,” he said. “And why would people want to pay more money for something that they won’t benefit from?”

RELATED: Program busing Flint workers to distant jobs holds promise across state

Transit advocates hope elected officials will help persuade voters like Howard to support a mass transit tax.

Khalil Rahal, director of economic development in Wayne County, said elected leaders have finally found long-sought regional consensus that could bring along the rest of the region.

“We’ve made progress around a plan we think the whole region can support. I think we all agree it’s too important to wait to 2020, and we need to strive for 2018,” he wrote to Bridge in an email.

“That being said, we’re not naïve and recognize there’s a lot of work before that can happen.”

Detroit city officials declined to talk in detail about changes sought by Mayor Mike Duggan.

Dave Massaron, chief operating officer for the City of Detroit, would only say, “the mayor and county leaders continue to have productive discussions about regional transit and a plan that the whole region can support.

“Some of the components being considered would require legislative changes. The city remains committed to working to having a regional transit plan on the ballot in November of 2018 that voters can support, as well,” he said in an emailed statement.

Macomb County officials also wouldn’t detail their proposals, but said the talks are constructive.

“The thing that’s been so beneficial about these conversations is they’re honest, practical and community driven,” said John Paul Rea, Macomb County’s director of planning and economic development.

“That’s something that’s incredibly powerful.”

No taxation without transit stations

County leaders also may ask the Legislature to change the boundaries of the RTA to make a tax increase more palpable to voters.

After the 2016 tax was defeated, transit officials learned many “no” votes came from those in communities that wouldn’t be reached by buses. Sixty percent of voters in Macomb County opposed the tax, while about half were opposed in Oakland County.

Hillegonds, the RTA’s chairman, said redrawing the boundaries might make sense for now.

“Comprehensive transportation in all four counties down the road probably makes a lot of sense, but we may have to be more incremental,” Hillegonds said.

Redrawing the boundaries to exclude outlying communities would reduce the number of taxpayers paying into the system, which likely would mean increasing the tax request from 1.2 mills that was sought in 2016.

The RTA needs as much time as possible to educate the public about the benefits of the new regional transit plan to maximize chances a November ballot initiative will pass, said Elisabeth Gerber, one of two Washtenaw County representatives on the RTA board.

“There’s a lot that has to happen in order for 2018 to be our moment,” Gerber said.

“We’re nervous, we want these decisions to get made quickly so we can move forward.”

(Editor’s note: Gerber and Paul Hillegonds are members of the steering committee for The Center for Michigan, of which Bridge Magazine is a part.)

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!