As Michigan ages, a shortage in health care workers explodes into a crisis

GRAND RAPIDS — Living alone in a Grand Rapids apartment, 84-year-old Nancy Klomparens clings to her independence — and has the injuries to show for it.

Poor eyesight contributed to a series of falls, as she said she’s fractured her back five times in the past four years. Once a week, she depends on a home care worker to drive her to the grocery store and help with shopping and other chores.

But like thousands of needy Michigan seniors, she’s endured a revolving door of home health aides, including a couple who abruptly quit.

“It’s devastating. I depend on that help,” said Klomparens, a mother of two who has lived alone for decades.

Related:

- Shortage of paid caregivers keeps family members up at night, hoping for 'something sustainable'

- Innovation, bonuses may help curb Michigan’s home health care shortage

Advocates for the elderly and those with disabilities say a long-time shortage of home health care workers has exploded into a crisis in Michigan amid the coronavirus pandemic, as aides are reluctant to risk their health for jobs that pay $12 to $15 an hour.

Michigan, which is 14th nationwide in the percentage of residents older than 65, has tried to stem the problem by increasing wages $2 an hour for state-subsidized home care workers last year as part of a budget deal that expires at the end of February

But pay is only part of the issue. Even before COVID-19, nurses aides were considered one of the most dangerous jobs in the nation, with a higher rate of workplace injuries than coal miners or truck drivers because of the lifting required to help the elderly.

And advocates warn the problem will only worsen as the state grows older and more health workers drop out of the field.

Rebekah LaFontaine, owner of a southeast Michigan home care agency, recently posted a plea on Facebook that summed up what’s at stake. A national AARP survey found that nearly 90 percent of those age 65 and over want to stay at home, but many need help to do so.

“We are in desperate need of caregivers for the elderly,” LaFontaine’s post stated. “If you can do only companion care, we have hours for you. If you can work only 1 hour/week, I need your help.”

LaFontaine owns Friends of the Family Home Health Care, which provides home care in Monroe and Washtenaw counties and part of Ohio. She said it’s a daily battle to find workers to place in homes where seniors need help.

“One week, we set up 25 job interviews and only five people showed up. We were only able to hire one,” said LaFontaine, who said her 80-worker agency is consistently short of workers that now serve 75 to 100 clients. She said she could serve up to 200 more clients if she had the workers.

“People are afraid of going into the homes and getting COVID. Some are afraid of getting COVID and passing it along to a client and then feeling responsible for that.”

Christine Vanlandingham, CEO of the Region IV Area Agency on Aging in southwest Michigan, said it doubled pay for home care workers with COVID-19-positive clients as a stopgap measure to encourage them to stay with a high-risk job. That’s atop the $2-an-hour state wage hike.

“These workers are doing hands-on, intimate, in-person care that puts them at extreme risk of COVID. We can provide all the protective equipment, but social distancing is not something you can do while you are giving a bath or helping someone on a toilet.”

Despite the added hazard pay, Vanlandingham said some workers continue to flee for safer and easier jobs.

“To ask these folks to do this high-risk work for what they are paid really is unconscionable,” she said.

Democrats have included wage increases for home health workers as part of their national platform for years, while President Joe Biden proposes a $15 an hour minimum wage as one piece of his $1.9 trillion stimulus plan.

The measures face resistance in Congress, though, and critics say raising wages could trigger unintended consequences, increasing costs for patients, government and insurance companies and perhaps even lead to service cuts for the elderly.

It could pose even deeper wage issues, they say, in regions of the country where average wages are below the national average.

A more targeted approach to home care wages — raising Medicaid reimbursement rates for care — faces hurdles as the system is struggling with funding.

The COVID-19 pandemic is driving up overall Medicaid enrollment and costs, prompting a $550 billion shortfall through 2022.

Rather than raising wages for workers, critics say, cuts to the program are far more likely.

‘Astronomical turnover’

In the meantime, industry groups estimate Michigan has a shortage of 34,000 direct care workers out of a current work force of about 120,000, a category that includes home health and personal care aides, as well as nurse aides.

That gap could stretch to a shortage of more than 200,000 workers by 2026, according to PHI, a New York City-based nonprofit policy and advocacy organization.

While part of that is because more elderly will need help to stay in their homes, PHI also projects that 170,000 workers will leave the field in Michigan by 2026.

And experts warn the crisis could be particularly acute in Michigan, with the number of those aged 75 and older expected to rise 62 percent to 1.2 million by 2040. By then, 1 in 9 state residents will be older than 75.

While the need for care grows, the workforce for home health aides will likely shrink: A fifth of home health workers now are 55 to 64, and that population itself is expected to fall by up to a fifth in Michigan by 2040, according to state estimates.

“As the Baby Boomer population continues to age, you have to look at the younger people who essentially make up the workforce, and that is a shrinking trend,” said Barry Cargill, executive director of the Michigan Home Care & Hospice Association trade group.

“That sets the foundation of why we have a problem. As people age, their dependence on in-home care becomes much greater and our Baby Boomer population is nearing the age where home care is going to be an essential service to keep them in their home.”

Clare Luz, a Michigan State University gerontologist, said the shortage of direct care workers was brewing years before COVID-19 because the pay is marginal and the work is difficult.

"These conditions contribute to not only a shortage, but an astronomical turnover rate that destroys continuity of care and keeps the system churned up,” Luz said.

In 2018, according to one national estimate, the average turnover rate of direct care workers reached an all-time high of 82 percent. That was 15 percent higher than the previous year.

Hourly pay rates per clients to home health agencies vary under Medicaid, averaging about $13 an hour, according to PHI. Agencies receive $16.08 an hour through Medicaid for clients, not including the $2 an hour pay increase, leaving razor-thin margins for home health agencies.

‘You can make more at McDonald’s’

LaFontaine of Friends of the Family Home Health Care said she’d pay more to her clients if she could. But LaFontaine said Medicaid’s payments are barely enough to meet her expenses and then pay her workers.

“I personally think caregivers ought to make $20 to $25 an hour. I think that’s what they are worth. But we are not in a situation where we can afford to do that.”

Many direct care workers must patch together a series of clients, a half-dozen or more, to try to earn a living wage. Significant numbers fall short, as nearly a fifth of Michigan direct care workers live below the poverty line, nearly a third depend on food stamps and a third lack affordable housing, according to PHI.

Their prospects for the broader job market may be limited because 46 percent lack education beyond a high school degree, according to PHI.

Carrie Cater, a case manager for 22 years at the Area Agency on Aging of Western Michigan, said it’s little wonder workers continue to leave this field for fast food jobs, retail work or entry-level factory work.

“You can make more at McDonald’s,” Cater said.

“You can make more at working in small industries, where you go to one place for your job instead of having to go from house to house to house. You really have to have a personality of helping people to be a direct care worker.”

State officials also identified the lack of training as a key barrier to retaining personal care and home health aides in the long term, said Dr. Alexis Travis, deputy director of Michigan’s Aging & Adult Services Agency.

“We are hearing from direct care workers that they are not appropriately trained to do their work. We need to provide them with the skills they need to be successful.”

Travis said adding training requirements for all direct care workers, along with the establishment of professional standards, is among the proposals under consideration by a state direct care advisory committee.

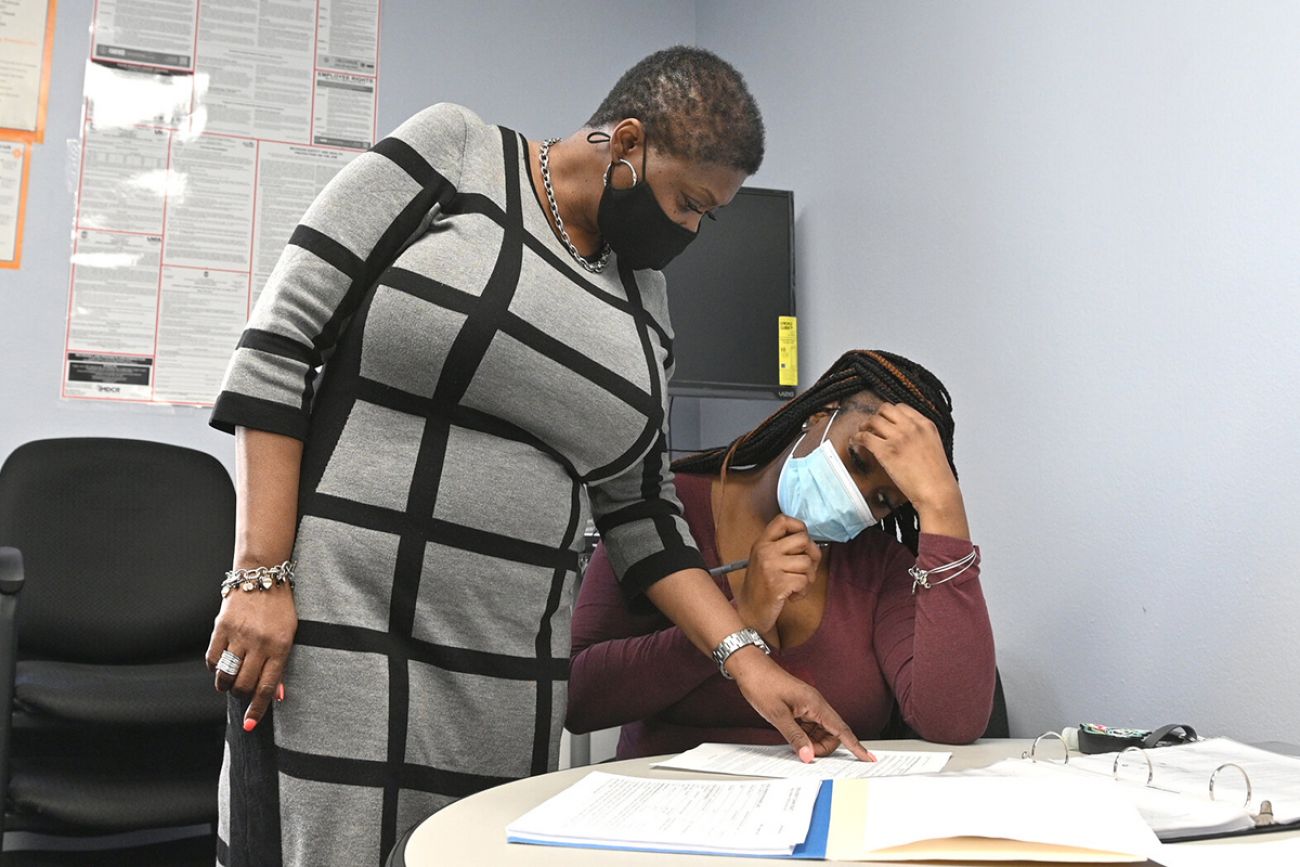

Addus Home Care in Detroit serves approximately 400 clients in the city and Wayne County and its sister company, Arcadia, aids an additional 50 clients in Birmingham.

The Detroit-based agency struggles to recruit, as 80 percent of caregivers rely on public transportation, rideshare services, or family to get to their assignment, said its director, Dawn O’Neal.

“When you have a two-hour shift and you arrive on a bus to see a client to take care of their needs for bathing or preparing a meal, putting a load of laundry in for two hours, and then get back on the bus to ride across town to the next client for another two hour shift — it's a challenge to recruit,” she said.

Roughly three-fourths of Addus workers rely on government assistance, as they make between $12,000 to $18,000 a year. Because of high turnover, the agency hires about 30 employees a month.

“People come to us without any experience. We are willing to train them and they go through an eight-hour training before they start…. (but) it’s still not enough to meet the demand of clients we have on a waiting list,” O’Neal said.

‘No complaints’

In Grand Rapids, Theresa Lindsey, 54, said she’s been a home care worker “since I was a teenager.”

Lindsey combined home care employment with a series of other jobs over the years, including factory work. She now has a couple of home care clients, in addition to home care support she’s paid by Medicaid to provide her husband.

Lindsey said she’s stuck with it because she likes helping people.

Related: Innovation, bonuses may help curb Michigan’s home health care shortage

“It has its good points. You get no complaints about that from me,” she said, before adding. “they need to start upping the pay.”

Three times a week, Lindsey visits the apartment of LaShella Johnson in Wyoming, a Grand Rapids suburb. For the past nine months, Lindsey has helped with cleaning, laundry, food preparation and taking medications. She’s been doing so for the past nine months.

A year ago, Johnson, 52, had a cancerous kidney removed. Shortly after that, she suffered the painful onset of severe rheumatoid arthritis. She also depends on nightly kidney dialysis treatments that she operates herself, with a home blood recycling machine that filters waste and extra fluids from her blood.

Her visits from Lindsey, Johnson said, are a lifeline that allows her to stay in her home.

“Without it, I would probably be in a nursing home. I would be in bad shape.”

It’s a similar story in Grand Rapids, where 84-year-old sight-impaired Nancy Klomparens wonders what she’d do without help from home health care worker Joan Langeler, who is a senior herself at age 68.

“She is my eyes,” Klomparens said.

Langeler started working with Klomparens in early January, the latest in a string of a half dozen workers who have assisted her in the past few years.

Langeler lives alone herself in an apartment, dependent on Social Security income and what she earns as a direct care worker to meet expenses. With seven clients scattered around the city, Langeler works about 36 hours a week.

Without that income, Langeler said, “I’d be having a hard time making the rent.”

But Langeler has plans to leave the state — and her clients — in the fall, to move to New Mexico to be with her daughter, who is struggling with the aftereffects of a car accident years ago. That means another change in caregivers for Klomparens and the rest of her clients.

“It will be very difficult to leave Nancy. Really, all of them. We all get attached to each other,” Langeler said.

This story was produced through the New York & Michigan Solutions Journalism Collaborative, a partnership of news organizations and universities dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about successful responses to social problems. The group is supported by the Solutions Journalism Network.

The collaborative’s first series, Invisible Army: Caregivers on the Front Lines, focuses on potential solutions to challenges facing caregivers of older adults.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!