One poor neighborhood, one struggling school

A couple years ago, Dawn Wilson-Clark was on a committee of residents who visited Detroit Community Schools in a westside neighborhood known as Brightmoor. Their task was to review it for Excellent Schools Detroit, a nonprofit that grades the city’s schools.

What they entered was a charter school that opened in 1997 and has struggled pretty much since. Only two of its students have ever been deemed college-ready by ACT college entrance exam standards. Teachers tended to be inexperienced. Turnover was high and enrollment was dropping in a neighborhood suffering from extreme poverty, blight and depopulation. And then there were the administrators. Though teachers were paid modestly, some administrators received six-figure salaries and were uncertified by the state. More troubling, at least two had been central figures in scandals elsewhere involving misappropriation of public funds.

Wilson-Clark knew little about the backgrounds of the administrators when she visited Detroit Community Schools. She was, however, encouraged by indications of progress that the school’s superintendent pointed out, including an improved graduation rate at the high school. The charter was also recently designated as a state “reward” schools, in recognition of academic gains.

But Wilson-Clark, who lives in Brightmoor, said the school is not yet good enough for her family. Her four school-age children are spread out among a private suburban school, an elementary in the Detroit Public Schools system and a charter school ‒ all outside of Brightmoor. She drives 130 miles a week shuttling them between schools.

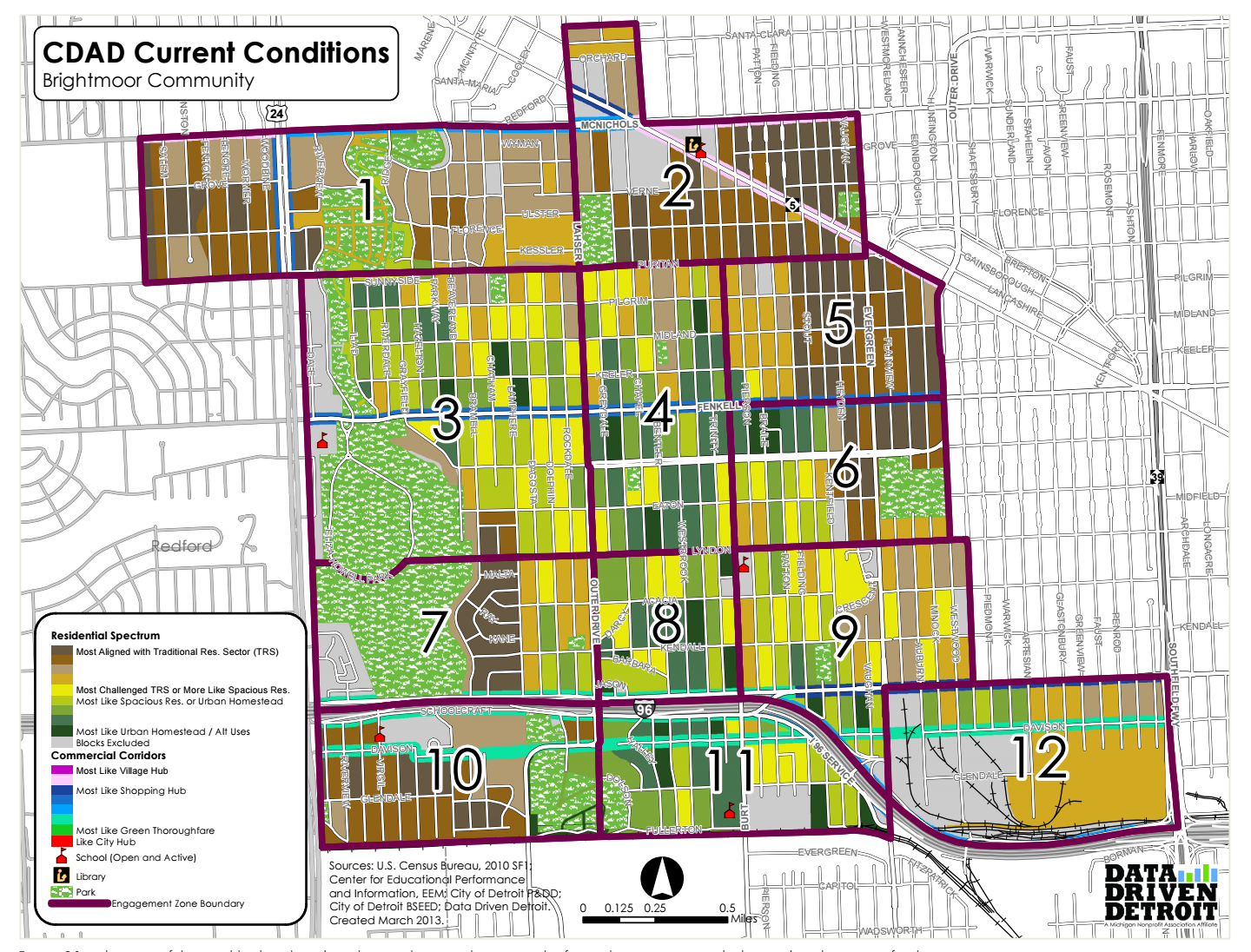

That’s because Brightmoor is an educational desert. With only five schools for children in kindergarten through eighth grade and a single high school to serve roughly 7,000 children, Brightmoor lacks the quality school options that residents say they need for their children.

High school is a particular void because the closest high school with decent academic outcomes is two miles outside the northeastern edge of the neighborhood; that would be Communication and Media Arts High, which has a graduation rate over 95 percent and nearly 60 percent of graduates going to college, according to state data.

For the impoverished residents of Brightmoor, the only neighborhood high school is Detroit Community Schools.

“We need more schools, quality schools in Brightmoor,” said Wilson-Clark. “A quality school, with people who have a track record and qualified teachers and proof they have served this population.”

Places like Brightmoor are now at the center of a debate in Lansing over whether a mayor-appointed commission should be approved to have authority over all public schools in Detroit, including charters. Supporters say a single, centralized authority is needed to oversee the traditional public schools and charters that open and close with regularity across the city, creating a glut of schools competing for students in some neighborhoods, and a dearth of quality options in struggling areas like Brightmoor.

Under a bill awaiting consideration in the House, a Detroit Education Commission (DEC) would be created, and one of its key roles would be to approve locations for new schools in Detroit for at least five years, so families like Wilson-Clark’s won’t have to leave their neighborhood in search of a decent education. But school choice and charter school advocates are against this approach, contending that a new commission would unfairly favor traditional public schools and limit choice.

Gov. Rick Snyder proposed the idea of a commission more than a year ago with support from the Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren, a group of community, education and business leaders co-chaired by Tonya Allen, CEO and president of the Skillman Foundation, which funds efforts to improve education in the city.

The commission debate is one of the major reasons the Detroit school reform legislation – which could also include $715 million in debt-relief for DPS – still has not passed the legislature a year after the governor proposed structural changes for Detroit’s school system. Legislators and special interests are also debating whether to allow a locally elected school board to regain authority over Detroit Public Schools after years of state emergency control.

Last month, Mayor Mike Duggan argued in Lansing that a mayor-appointed, seven-member commission would focus on locating schools in a manner that would help stabilize neighborhoods. The Detroit Regional Chamber of Commerce, which calls itself “pro-charter,” also supports giving a single authority power over public schools in the city.

“Parents in Detroit should have choices,” Brad Williams, vice president of government relations for the chamber, told the legislature. “I believe they should be good choices. And I believe they should not be limited to the neighborhoods that are often oversaturated with schools, while others are woefully underserved.”

Among the toughest opponents of the proposed Detroit Education Commission is the Great Lakes Education Project, an influential statewide school choice advocacy group. GLEP contends that a mayor-appointed commission would wield its power to limit charter schools.

“The new Detroit Education Commission puts all key education decisions in the hands of a few political appointees and is statutorily required to promote the interests of the new traditional school district over charter public schools,” Gary Naeyaert, GLEP’s executive director, claimed in a statement. “Further, we don’t believe there should be different accountability expectations in Detroit when compared to schools in the rest of the state.”

He said GLEP will continue to fight against the proposed commission while aiming to make the House bills “more friendly to parents and school choice.”

Troubled school leaders

In some areas of the city there are arguably too many schools. In southwest Detroit, for instance, where the birthrate is steady and population more dense, there are plenty of schools to choose from.

Similarly, in the the 7.2-square-mile area of greater downtown, with about 4,400 residents under age 18, according to a report by the Hudson-Webber Foundation, there are at least half a dozen adjacent high schools. By comparison, the seven-square-mile Brightmoor neighborhood has only one high school for 7,000 school-age children, according to the Brightmoor Alliance, a coalition of nearly 50 local organizations.

“What is it about downtown?” wondered the Rev. Larry Simmons, executive director of the alliance. “Do they have so many students?

“No. It’s a place where (people with) money are. Things tend to aggregate around people with money.”

Brightmoor, meanwhile, on the city’s western edge, has seen at least six of its public schools close over the past decade, including Redford High.

That leaves Detroit Community Schools, the long-undistinguished charter, as the only public high school in the area. The school serves children in kindergarten through 12th grade, 99 percent of whom are African American and 93.4 percent are low income, state data show. It reported a graduation rate of 88 percent in 2015, higher than the citywide average and up from 79 percent the prior year.

But low test scores indicate that the students they are graduating are not ready to pursue a career or a college education. None of the high school students tested in 2014-2015 were proficient on all four subjects on the ACT, a benchmark for career or college-readiness. Further, of the 1,053 students who took the ACT tests since the high school first offered it in 2006-2007, only two have met the college-ready standard in all tested subjects.

The school is run by former Detroit City Council member Sharon McPhail, a lawyer by training.

McPhail was hired as the school’s superintendent in 2012. She is perhaps best known as a serial candidate for city office and as an adversary-turned-defender of former mayor Kwame Kilpatrick. In 2003, as a city council member, she accused Kilpatrick or his backers of tampering with wires in her desk chair to give her an electrical shock. Five years later, as the city’s general counsel, she defended Kilpatrick against Gov. Jennifer Granholm’s efforts to remove him from office. McPhail has plenty of legal experience, but is neither a certified teacher nor certified school administrator, Michigan Department of Education records show.

There is, however, someone at the school with vast experience running an urban school: William F. Coleman III, the charter’s chief financial officer.

Coleman is the former CEO and superintendent for Detroit Public Schools. Former because Coleman was fired from DPS in 2007 after he admitted to recommending a friend to do work for a DPS contractor while the friend was under investigation in a school bribery scandal in Texas. That friend, Ruben Bohuchot, and a Dallas school vendor were later found guilty in Texas federal court of bribery and money laundering.

Coleman was also indicted in the Texas case but was allowed to plead guilty in 2008 to a reduced charge of attempting to influence a grand jury in return for testifying for the federal government, court records show. As a result, prosecutors also agreed to drop conspiracy, bribery, money laundering and obstruction of justice charges against Coleman in the kickback scheme, which the government valued at roughly $40 million.

According to the indictment, the men conspired to create shell companies to accept bribes on school technology contracts for low-income schools in Dallas, where Coleman had served as deputy superintendent and chief operating officer at the Dallas Independent School District. After testifying, Coleman received probation, was ordered to pay a fine and perform community service.

Coleman did not respond to requests for comment on his current role as chief financial officer at the Detroit school.

McPhail, likewise, declined to be interviewed by Bridge. She did, however, respond to questions by email. She wrote that she is proud of the school’s progress and hailed Coleman's experience, saying he has never done anything questionable at her school.

“His professional career has spanned decades,” she wrote. “He does great work here and also spends time with the kids, takes voluntary pay cuts and is always here for the students.”

Coleman is not the only school administrator with a controversial past.

The school’s dean is Sylvia James, a former judge. In 2012, the Michigan Judicial Tenure Commission recommended James be removed from the district court bench in Inkster, near Detroit, for misusing court funds.

The Michigan Supreme Court upheld that recommendation and removed James, finding that James "made numerous misrepresentations of fact" to the Judicial Tenure Commission, employed her niece against court rules and misappropriated funds intended for the court's Community Service Program, including money that was supposed to go to crime victims and the elderly in Inkster.

James treated court funds as her own “publicly funded private foundation,” the high court wrote, using money on items such as travel to conferences, shirts embroidered with her name, advertising and donations to charities she chose, including a school “Europe fund.” The court also found James “made numerous misrepresentations of fact under oath” during the investigation.

The Supreme Court concluded she should be removed to “protect the people from corruption and abuse.”

James has since filed a lawsuit alleging the Judicial Tenure Commission discriminated against her by not filing “formal disciplinary complaints against Caucasian and male judges who were accused of conduct similar” to hers, as an African-American female.

James also did not respond to requests for comment.

As it happens, Sharon McPhail was James’s attorney in 2012 when James faced the allegations from the Judicial Tenure Commission. McPhail wrote Bridge that the school is “fortunate” to have James as the dean.

“As a lawyer, who is licensed, she offers the students a level of insight that others have not been able to deliver. She spends much of her personal time and money on our kids,” McPhail wrote.

Another administrator at the school also has a bit of controversy in her past. Patricia Peoples, the school’s director of human resources, is a cousin of former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick. She once served as Detroit’s deputy director of human resources during Kilpatrick’s disgraced administration. She was among more than two dozen city officials who were friends or relatives of the now-imprisoned former mayor when he was under investigation. She avoided being held in contempt of court in 2008 by appearing before a Wayne Circuit Court judge who demanded she comply with investigative subpoenas seeking city documents and information involving shredded materials in the Kilpatrick scandal.

Peoples did not respond to requests for comment.

McPhail defended Peoples’s qualifications and ethics, saying she has an extensive background in human resources. “She is committed to loving our students and is always willing to take pay cuts and do whatever is required for them,” McPhail wrote. “She mentors students in addition to doing a great job. Also, Ms. Peoples was never involved in the scandal.”

The staff at the school also includes McPhail’s brother, Roger McPhail, the school’s grant writer. McPhail said she disclosed their relationship to the charter school’s board and had nothing to do with the school’s staffing company hiring him.

Michael Parish, who heads the Bay Mills Community College charter school office, which authorizes the school to operate and oversees the board, told Bridge the hiring of McPhail’s brother “creates a conflict.” But he said any accountability to take action on a potential conflict of interest rests with the Detroit Community Schools’ charter school board, saying “this decision is within the purview of the DCS Board.”

As for the other administrators, Parish demurred, saying Bay Mills “has no opinion or information upon which to comment.”

Detroit Community Schools board members did not return calls or emails from Bridge seeking comment. They include: Richard Robinson, lecturer at University of Michigan-Dearborn; Patrick Devlin, secretary-treasurer of the Michigan Building Trades Council; Nicholas Tobier, associate professor at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; Robert Dulin, a retired pastor, and Toney Stewart, executive director of the Michigan Council of Carpenters, according to the school’s website.

Certification issues

According to the Michigan Department of Education, some administrators at the school appear to be in violation of state law because they have not received state certification for their positions.

Michigan law requires school administrators who oversee instruction or business operations to be certified by the state within three years of taking the position.

Neither McPhail, who started in 2012, nor school principal Echelle Jordan, who has been there since at least 2013 according to payroll records, are certified administrators, according to state records. Nor is William Coleman, the chief financial officer. By law, if an administrator is not certified within that three-year window, the school “shall not continue to employ the individual as a school administrator,” Bill Disessa, a spokesman for the Michigan Department Of Education, told Bridge in an email.

McPhail offered a curious defense for her lack of superintendent certification. She told Bridge she does not in fact hold that position.

This despite the fact that McPhail is referred to as the school’s superintendent in school literature, including audits, board meeting minutes and on the school website. Indeed, in one of several emails she sent Bridge, McPhail attached a memo she wrote in which she identifies herself as superintendent. In another earlier email, McPhail wrote that she “earned less than most superintendents.”

Nevertheless, when asked about her lack of certification, McPhail responded that she is not the superintendent. Instead, she said, she is the school’s chief administrative officer, and therefore doesn’t need certification. The school’s website shows that on March 23, after Bridge inquired about the certification issue, McPhail’s “chief administrative officer” title was posted on the site.

It remains unclear whether, even under her newly posted title, McPhail can avoid the state’s certification requirement. State law requires a superintendent, principal, assistant principal, administrator of instructional programs or chief business official to be certified. Disessa, of DME, added that anyone with overall management and oversight of a school district or charter school is considered a superintendent and must comply with the state’s certification law.

Schools that violate certification requirements can face stiff penalties. By state law, the state can cut school aid payments to the school to recoup the amount of money paid to administrators during the time they worked at the school without a license. And any school official who knowingly employs an unlicensed administrator is guilty of a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of $1,500 for each instance.

Six-figure salaries are not unusual at McPhail’s school, if you’re an administrator.

McPhail’s salary is $130,000, with total compensation at $160,745 when benefits are added, to oversee a school of fewer than 800 students. That’s more than superintendents receive in traditional school districts such as Eaton Rapids (south of Lansing) and Ludington, in west Michigan north of Muskegon, school districts with three times more students than McPhail’s school.

Coleman and Jordan also made six-figure salaries, according to 2013 payroll records obtained by Bridge. In September 2013, Coleman was paid $4,375 for a two-week pay period, or a rate of $113,750 per year. Jordan, the principal, made $4,166.83, an annual rate of $108,337.

By comparison, the school's teachers, who average less than five years experience, average $42,000 in earnings per year, according to the school. The average pay for teachers in Michigan is about $62,000, state data show.

Asked why top administrators receive six-figure incomes at the school while teachers are paid so little, McPhail wrote, “Why in the world would you expect an administrator to be paid less than a teacher?” She added that she and other administrators have accepted multiple pay cuts to help the school keep a balanced budget.

An up-to-date, complete list of the school’s staff names, titles and incomes is not available because, like most charters in the state, the school hired a private staffing company, in this case Midwest Management Group Inc., which is not subject to the state’s public records law. The company employs all staff ‒ except McPhail who has a contract with the school, said Ralph Cunningham, owner of Midwest Management Group. He said the school employs 95 workers, but declined to give further details.

Parents interviewed as they picked up their students after school recently said they had few complaints about Detroit Community Schools. However, they noted concerns about high teacher turnover and the poor condition of the half-dozen trailers that house classrooms for elementary and middle school children.

Pamela Duley has had children at the school for eight years. Her daughter is in seventh grade and aside from her daughter having to wear a coat when the classroom in the trailer gets too chilly, she has few worries about the school. Duley’s older daughter graduated and is now a student at Henry Ford Community College.

“I like the school,” Duley said. “I went to Cody (High),” she added, referencing a high school near Brightmoor with lower academic scores than Detroit Community Schools. “And I didn’t want Cody for my kids.”

Emmett Harris, whose two children started attending the DCS high school this school year, said security is good, students rarely fight each other and teachers allow students to retake tests to correct mistakes.

“They won’t let you fail,” he said.

Difficult transition

DCS opened in 1997 with an elementary school, but grew as other schools in the area closed. In 2004-05, the school had 387 students. In 2007-08, after the closure of Redford High and several area elementary schools, DCS enrollment jumped to 956.

In 2014, after 17 years, Saginaw Valley State University refused to continue as the authorizer for Detroit Community Schools, citing poor educational performance and administrative “dysfunction.” But the school was saved by another authorizer.

Bay Mills Community College, located in the Upper Peninsula, granted the school a charter in 2014 which allowed it to remain open. Parish, of Bay Mills, said the authorizer jumped in because the school is “important to the area” and Bay Mills believed the school could improve with a more cooperative relationship with its authorizer.

Education Trust-Midwest, a nonprofit education advocacy group, this year gave Bay Mills a “B” grade on its Authorizer Report Card based on performance and improvements seen at the 47 charter school Bay Mills authorizes. At the same time, Ed Trust labeled the Brightmoor school’s elementary grade level achievement as “among the worst charters in Michigan.” (see page 21). Last year, only 6 percent of the school’s students in grades 3 to 8 were deemed proficient in math and English on the state standardized test. The elementary/middle school ranked in the bottom 6 percent in the state for 2013-14.

Still, there has been some improvement.

The high school moved up from being ranked as one of the bottom 5 percent of schools in the state in 2013-14. It is now ranked in the bottom 25 percent. As a result, the high school was labeled by the Michigan Department of Education as a “reward” school last year for the pace of its improvement, a point of pride to McPhail.

“This school has come from the very bottom to become a designated ‘Reward School’ in just four years. Our graduation rate exceeds that of nearly all other schools in the city,” McPhail wrote Bridge. (The school’s 2014-15 graduation rate was 88 percent compared with 77 percent for DPS schools.)

“Most often, we do not get children who are prepared academically. We must teach them the basics as well as the grade level curriculum. We do a great job of that.”

However, among 84 eleventh graders who took the ACT college entrance exam last year, state records show none scored at proficiency rates on all four subjects of the ACT, a benchmark that determines if a student is ready for college and career training.

While the Detroit Community Schools has the only high school in Brightmoor, the neighborhood has four other schools that serve elementary and middle school children. They include Old Redford Academy and Detroit Leadership Academy (which has ninth and tenth-grades), both charter schools; Murphy Performance Academy, a charter school school run by the state reform school district, and Gompers Elementary-Middle, a part of the Detroit Public Schools.

All struggle academically.

The fact that Brightmoor’s schools are operated by different entities is not insignificant, said Simmons, executive director for the Brightmoor Alliance. Because charters and traditional public schools compete for students and the funding they bring, these schools have few incentives to pool resources to better serve children in the neighborhood.

Simmons echoes Excellent Schools Detroit, the mayor, the Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren and the Chamber of Commerce in support of a Detroit Education Commission to be appointed to act as a neutral board responsible for determining where schools should open and close throughout the city.

A Detroit Education Commission, if it works as proposed, would ensure schools are opened or closed in the most effective way for students – not the cheapest way, he said.

Simmons said Detroit Community Schools should be commended for its commitment to Brightmoor, but said the community needs more and better schools.

“The inner-city high school students are some of the most difficult students to teach. They arrive with histories and difficulties. There’s not a lot of desire or competition to serve that community,” he said.

“There’s no backing away from this,” Simmons said. “We’re either going to invest in these children or reap a whirlwind 15 to 20 years from now when these kids are expected to enter the workforce and are absolutely essential for the operation of the American economy and they’re ill equipped.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Detroit Community Schools, opened in 1997, is a K-12 charter school in the impoverished neighborhood of Brightmoor on the city’s far west side. Due to school closings, it is the only public high school in the seven-square-mile area. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey)

Detroit Community Schools, opened in 1997, is a K-12 charter school in the impoverished neighborhood of Brightmoor on the city’s far west side. Due to school closings, it is the only public high school in the seven-square-mile area. (Bridge photo by Chastity Pratt Dawsey) Sharon McPhail, a former Detroit city councilwoman and former general counsel for the city, became superintendent of Detroit Community Schools in 2012.

Sharon McPhail, a former Detroit city councilwoman and former general counsel for the city, became superintendent of Detroit Community Schools in 2012. William F. Coleman III, the former CEO and superintendent of Detroit Public Schools, is the chief financial officer at Detroit Community Schools. He accepted a plea deal in 2008 to interfering with a grand jury in Texas, connected with a bribery and kickback scheme involving Dallas schools.

William F. Coleman III, the former CEO and superintendent of Detroit Public Schools, is the chief financial officer at Detroit Community Schools. He accepted a plea deal in 2008 to interfering with a grand jury in Texas, connected with a bribery and kickback scheme involving Dallas schools. Sylvia James was removed as a district court judge in Inkster in 2012. The Judicial Tenure Commission recommended her removal after its investigation revealed that James spent court funds on items and causes personal to her. She is dean at Detroit Community Schools.

Sylvia James was removed as a district court judge in Inkster in 2012. The Judicial Tenure Commission recommended her removal after its investigation revealed that James spent court funds on items and causes personal to her. She is dean at Detroit Community Schools. Brightmoor

Brightmoor