Michigan Black lawmakers to sue redistricting commission over new maps

Jan. 4, 2022: Battle brewing among Michigan Democrats over new political maps

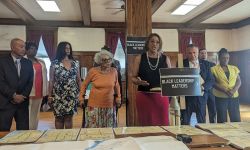

LANSING — A contingent of 15 Detroit Black lawmakers and leaders announced Monday they will sue the Michigan redistricting commission over recently approved state legislative and congressional maps.

In a media event in Detroit, the lawmakers — including six incumbents and two former state representatives — argued the maps dilute the power of Black residents in the city of Detroit and violate the Voting Rights Act, the 1965 law designed to allow minorities to elect candidates of their choosing.

“We have to get into this fight and protect generations because representation matters,” state Rep. Tyrone Carter, D-Detroit, who is one of the plaintiffs, said Monday morning.

Related:

- New districts give Democrats chance to flip Michigan Legislature

- Congressional map adopted by Michigan panel gives Democrats 7-6 edge

“We have to make sure that we get our fair share — if we're 13 percent of the population, then we need to represent that in the statehouse.”

Nabih Ayad, a Detroit-based attorney representing the lawmakers, told reporters the maps adopted late last month by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission discriminate against Detroit voters.

“Regardless of what the intent or the motive of the 13 commissioners here was, the fact is that the end result is that it strips away the voters and the representatives of those communities, especially in the city of Detroit,” Ayad said.

He added more people would be added to the complaint before it's filed.

Edward Woods III, spokesperson for the redistricting commission, told Bridge Michigan in an email the panel learned about the alleged lawsuit through media reports.

“We believe in the advice of our Voting Rights Act legal counsel that we comply with the Voting Rights Act,” Woods said.

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission was created after voters in 2018 overwhelmingly supported a constitutional amendment that changed how the state drew maps.

Until then, the party in power in the Michigan Legislature was in charge of drawing districts every 10 years after the decennial census.

Michigan is a divided state that leans slightly Democratic, but Republicans for years controlled a disproportionate number of seats in Lansing despite sometimes receiving fewer total statewide votes than Democrats.

The new maps are touted for partisan fairness and giving Democrats a chance to flip both state chambers.

But the maps, which are scheduled to go into effect in 60 days (around the first of March), significantly reduce the number of Black-majority districts in the state.

Monday’s announcement of litigation — which could be the first of several lawsuits — followed months of discontent among Black voters and activists.

The new congressional map has no districts in which Black voters are the majority. There were two in districts created by Republicans in 2010 that expired last year.

The state Senate map also has no Black-majority district, down from five, while the new state House map has seven majority-Black districts, down from 12.

The commission followed the advice of its voting rights attorney Bruce Adelson and its partisan fairness expert Lisa Handley.

Both have said that the commission didn’t need to draw districts that were over 50 percent Black — like the current districts — in order for them to be compliant with the Voting Rights Act.

They suggested lowering the percentage of Black voters to ensure the creation of more “opportunity districts''. According to the Loyola Law School, these are districts where white voters cross over with minority voters to elect the minority-preferred candidate.

The commission agreed, and it drew districts that stretched from Detroit, the nation’s Blackest city, to white suburbs. About 1 million of Michigan's 1.4 million African-Americans live in the city and surrounding three counties.

Rep. Tenisha Yancey, D-Detroit, who is expected to join the forthcoming suit, contended the commission used flawed data to create the districts.

The panel used mostly results from general elections when it drew the maps because there haven’t been many competitive primaries in the state.

But Yancey said if they looked into primary data they would have noticed s white voters often do not vote for the same candidate as Black or minority voters.

She said she experienced this firsthand when she ran for office and had to campaign in the much whiter communities such as the Grosse Pointes.

Yance won an 11-person Democratic primary for the old House District 1 in 2017. She got 2,215 votes, while the runner up was a white woman who got 2,017 votes.

That district is 67 percent Black, and 28 percent white. But Yancey’s new district would be 54 percent white and 44 percent Black.

The district leans heavily Democratic, so the winner of the primary is all but guaranteed to win the general election.

“I would not have won my election without the support of my Detroit constituents,” Yancey said. “So if you eliminate some of those votes by drawing a line to draw some of those Black voters out or Black Detroiters out of my district, there will be no more Tanisha Yancey.”

“We know that white people don't vote for us,” added Yancey, who is term-limited. “So do we wait for it to happen, or do we do it now?”

But some experts have said that historically, reducing the Black voting age population in districts might not have a negative impact.

The redistricting commission’s attorneys, for instance, argued that Black voters had less clout in the old maps because they were so heavily concentrated in single districts.

Spreading them out may allow them to elect more candidates and could “actually increase Black representation,” Michael Li, the senior counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program, told Bridge Michigan in October.

“The reality is that Black voters are very politically cohesive,” said Li, who studies redistricting. “If they vote cohesively (their candidates) might get elected in districts that are below 50 percent Black.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!