Suspect you have coronavirus in Michigan? Your doc may not want to see you.

Donn Hinds would like a coronavirus test, please. And he seems to make a pretty good case. He’s 69 years old and has struggled for days with the classic symptoms he’s read about online: A 101-degree fever, occasional chills and coughing. “Lots and lots” of coughing.

“I’m short on breath, even now,” he told Bridge Magazine in a phone interview from his home in Flushing, where he lives alone and has put himself into self-quarantine.

He also recently traveled to Belize, where he dined with fellow travellers from Italy, which has been so overwhelmed with coronavirus cases that it has essentially shut down.

But after being bounced from his primary care doctor to a testing lab, to the county health department and a local hospital, Hinds pronounced himself at a loss.

“This,” he wrote on Facebook, “is a hell of a way to handle a pandemic.”

Hinds’ star-crossed efforts illustrate the frustrations faced by sick people and doctors alike as governments and hospitals calibrate on the fly who should receive coronavirus testing and who, for now, should not, as the tests remains limited and the illness spreads.

And as many Michiganders may soon learn: The very doctor who might have treated you in the past for, say, a cold or flu may now turn you away.

Or they may have staff first take your temperature or draw blood while you’re still in the parking lot, far from the waiting room.

And those routine office visits you’d scheduled in the coming weeks? Don’t be surprised if they’re canceled.

The new protocols are about protecting all patients, said Dr. Faiyaz Syed, chief medical officer for Michigan Primary Care Association, a network of community health centers that in 2018 served more than 709,000 Michiganders.

The social distancing you’ve heard about at work and in public? It’s the same for patients, Syed said.

“So if you get a patient who is sick … and they are waiting in the waiting room, and you have like 10 other people, you are exposing potentially those 10 other patients,” Syed said.

- How to prepare for coronavirus in Michigan. Step 1: Breathe

- How to make your own hand sanitizer during coronavirus shortage

- Can I get tested for coronavirus in Michigan and other questions answered

- The first line of defense against coronavirus: Try soap, not a mask

“Everybody's used to the classic ‘Come to the office and wait to see the doctor,’” said Dr. Peter Gulick, an infection disease expert at McLaren Greater Lansing Hospital and the Ingham County Health Centers. “I don't want you to get the idea that we've not seen patients. We're just trying to do a little better triage.”

Gulick said Friday that he was planning to spend the afternoon cancelling upcoming, routine visits. He also expected some annoyed or confused patients.

“This is creating a whole new way of practicing now,” he said.

A new world

The changes can be infuriating and scary for someone miserable with a fever and cough and anxious as a virus strain unknown until just three months ago continues to claim lives.

By Saturday morning, more than 5,500 people around the world had died, including 47 in the U.S. Nobody has died so far in Michigan, but there were 25 confirmed cases by late Friday, including a handful of people with no recent travel history or known contact with an infected person, a worrying trend.

The U.S. government’s sluggish response, particularly the lack of broadly available testing, has been hammered by critics, and acknowledged by the federal government’s top infectious disease expert. On Friday, President Trump declared a national emergency, which among other things is intended to speed up production of testing to better track COVID-19’s path.

Until that happens, Michigan clinics and hospitals are being selective about who gets tested.

“It seems like a terrible thing to say, but if you have mild symptoms, or you’re not immunocompromised, if you’re under the age of 70, going in will only put other people at risk,” said Dr. Sandro Cinti, a professor of infectious disease at the University of Michigan, who addressed public questions during a Facebook Live broadcast Friday. “You (have an) 80 percent chance or more of doing just fine on your own at home.”

Mike Radtke, a city council member in Sterling Heights, certainly hopes so. He said he tried to get a coronavirus test after developing a fever, sore throat and cough late last week. He’d also recently met with officials who had traveled from a known hotspot country.

Radtke said his primary care doctor was “fully booked,” so he called Beaumont Hospital, where a staff member asked him several screening questions and deemed him not to be a high risk.

“Because my symptoms are mild and I can self-isolate at home, they asked me just to do that,” Radtke said. With his fever dissipating, he thinks he’ll be fine, but he was “frustrated” by the experience and wanted to get tested to make sure he didn’t get any family members sick.

“I think we need more testing kits and we need wider spread of testing kits in the community, because I don’t understand how you can even get your arms around the situation if you don’t know who’s sick and who’s not,” he said.

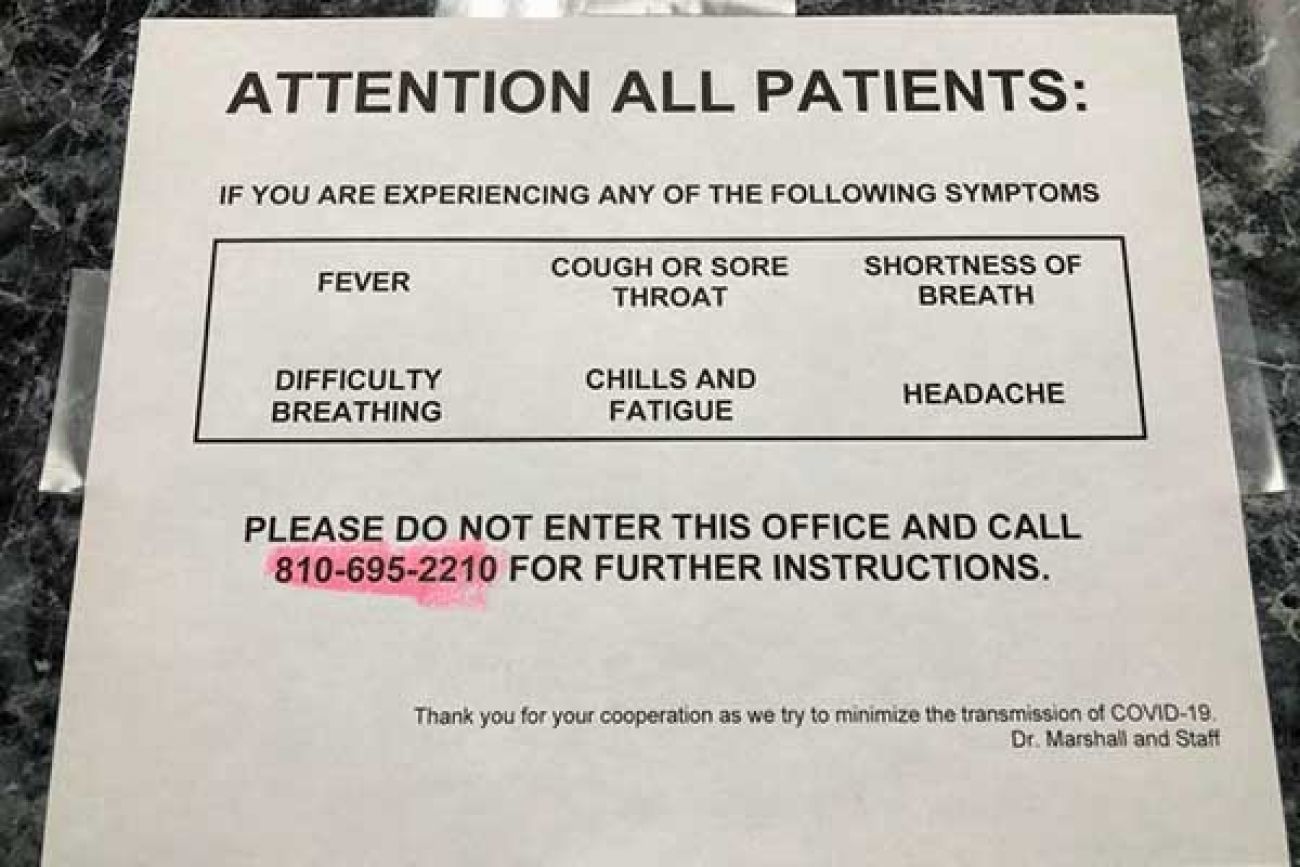

In Grand Blanc, family medicine doctor Mary Marshall taped a sign outside her office this week, near a new display of tissues and hand sanitizer. To those with possible symptoms of coronavirus, the sign warned: “Please do not enter this office.”

They are to call instead “for further instructions.”

Her staff would direct a patient with, say, highly contagious measles or chickenpox to do the same, but they’ve never had to put up a sign before.

These are different times, though, days filled with anxiety, said Marshall, who chairs the Michigan Association of Family Physicians.

“People get so panicked (about coronavirus), they don't give doctors’ offices 10 or 15 minutes to even call back. … At this stage, (they) just drive up and come to the office,” she said.

It’s such a concern, in fact, that some health centers and doctors soon will begin screening patients who call with flu-like symptoms in parking lots outside their offices, Syed and Gulick told Bridge Friday.

At Central City Integrated Health in Detroit Friday, health staff were taking the temperatures of everyone who came through the door before allowing them to ride the elevator to reach the clinic's medical, behavioral health and dental offices, said Dorothy Austin, the clinic’s director of nursing.

Beginning Monday, staff will be stationed outside the door, stopping visitors before they enter the building to take their temperature and screen them with questions like: Do you have a cough?

They were still scrambling Friday to figure out how to stage the checkpoint with a desk or awning. “This is such a rapidly-changing situation. The changes are nearly day-to-day,” said Austin, whose 30-plus-year career has taken her through H1N1, MERS, SARS and other outbreaks.

Telemedicine, or virtual care — used sporadically through the state — may ease the expected crush of calls from anxious patients like Hinds, and help healthcare workers distinguish those possibly infected by the coronavirus from other patients.

On Thursday, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced that the state’s Medicaid program will reimburse doctors who provide care remotely to recipients in their homes — something Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, Blue Care Network of Michigan, Priority Health, Meridian, CVS Health, McLaren, and Health Alliance Plan insurance plans also are doing.

Before the change, Medicaid coverage limited telemedicine to certain sites that met privacy requirements, so a patient would typically have to go to a local doctor’s office to access a specialist many miles away. Using software with extra privacy security, a doctor can now “see” a patient by, say, using a cell phone to speak with them.

When can I get a test?

In the meantime, the public has received mixed messages about who can be tested, and where they might go.

For weeks, only the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was testing cases. Then, state labs came online. Within the past two weeks, private labs have begun offering tests as well, leaving some with the mistaken understanding that the tests should be easy to get.

President Trump famously said last week “anybody that wants a test can get a test. That’s what the bottom line is.” He was wrong.

“We don’t have that capability yet,” said Cinti of U-M. “We are testing the people who are the highest risk only.”

Hinds, of Flushing, said his odyssey began when he called his primary care doctor to report his symptoms. The doctor instructed him not to come into the office because he might infect other patients.

He went to a local Quest Diagnostics facility with a note from his physician ordering a test, but was turned away. A Quest spokesman told Bridge that doctors must collect a specimen for the lab to test.

Hinds said he then spoke with the Genesee County Health Department and to staff at Hurley Hospital, which has posted a message on its website saying “coronavirus (COVID-19) testing is NOT available for the general public on request.”

“Most cases of COVID-19 are mild respiratory illnesses,” it reads. “Similar to testing for other infectious diseases, such as the flu, the first step is a full evaluation by your Primary Care Provider."

A retired biology teacher, Hinds said he is “not afraid of the system” but feels he’s fallen through the cracks as health care providers grapple with the crisis and brace for the global pandemic to get worse here before it gets better.

“I suspect the average person after they got turned down once or twice would say enough’s enough,” Hinds said.

He said he is getting food deliveries from friends, including state Sen. Ruth Johnson, R-Holly. His home sits next to the Flint River, and he spent time outside on Wednesday stacking wood.

“I moved in slow motion,” he said. “I probably stacked half a face cord, and I was beat. And I’m in good shape.”

For now, Hinds is content to stay put and follow the governor’s advisory to self-quarantine until he recovers from whatever it is he has.

“By the way,” he wrote on Facebook, “I need a new doctor.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!