In a city filled with blight, one Detroit neighborhood gets help while another waits

Gray Carter and Sherrod Hicks live a few blocks apart in the Brightmoor neighborhood on Detroit’s far west side. They like where they live, but they both see a need for the city to tear down more abandoned homes to make their areas safer and better looking.

Carter is going to be disappointed, at least for a while. He lives in a 1 ½-story home on Lyndon, near Chapel, in a district that is not targeted for additional demolitions by the city in the foreseeable future.

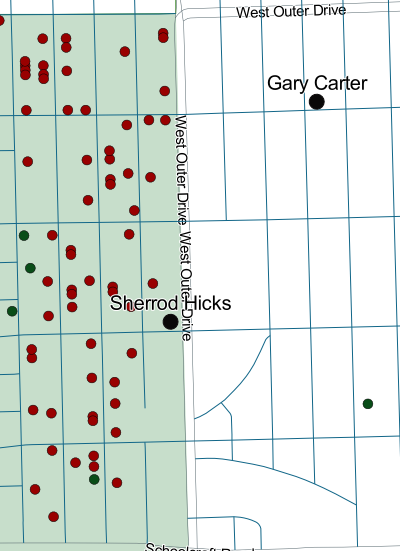

In contrast, Hicks, who operates an adult foster home for seven clients on the west side of Outer Drive, at Acacia, has watched as heavy machinery has ripped down a handful of abandoned homes in recent weeks. In the six or so blocks west of Hicks, the city has demolished or is planning to knock down about 30 homes.

In Carter’s neighborhood, just two blocks east: Zero.

This tale of two neighborhoods – with one seeing aggressive demolitions and the other, often just blocks away, seeing no activity – is being reprised across Detroit’s 139-square-mile surface as the administration of Mayor Mike Duggan steps up efforts to address one of the Detroit’s most pressing problems – abandoned buildings – by targeting specific neighborhoods.

That means other areas will have to wait.

Boundaries between targeted neighborhoods and wait-listed areas exist across the city, and on this stretch of Brightmoor, the dividing line is West Outer Drive.

The streets to the west of Outer Drive will see the bulldozers and dump trucks. Streets to the east will have to wait, though this particular area has seen numerous demolitions in past years.

“You had to make a dividing line somewhere,” Craig Fahle, director of public affairs for the Detroit Land Bank Authority, said of the city’s detailed blight removal strategy.

A targeted approach

Experts say the city’s approach of prioritizing neighborhoods makes sense. They say spreading the first $50 million in federal mortgage rescue money equally across the city would have made less of an impact and perhaps made a difference only to nearby homeowners. Targeting specific, densely packed neighborhoods, as Detroit has chosen to do, helps keep these areas intact and prevents more residents from fleeing Detroit.

Outer Drive near the homes of Carter and Hicks separates two distinct neighborhoods. On the east side of the street, where Carter lives, past demolitions have left the terrain looking like a patch of rural Michigan, with views that stretch several blocks.

On the west side of Outer Drive – around Hicks’ home – the neighborhood is much more dense, with newer homes and well-kept older structures.

On both sides of the line, though, there are numerous abandoned homes in various stages of disrepair, plus small illegal dump sites. Near Carter’s house, there’s even an abandoned pleasure boat listing on a vacant lot.

Not surprisingly, Hicks, 54, approves of the city’s demolition strategy.

“They tore down a house over there a couple of weeks ago and leveled it out,” Hicks said, then pointed to a vacant lot that was the site of a tear-down months ago. The lot has become an informal park in nice weather.

“They’ll really be enjoying themselves, playing horseshoes and everything,” he said of his clients.

While Hicks said his clients walk around the neighborhood with no problems, two abandoned houses on the next block have become a concern.

“I’ve been seeing cars parked there at night time. You see them going in there at night. Maybe they’re in there getting high or something,” he said.

On the east side of Outer Drive, Carter, 60, described the neighborhood as tranquil. “There’s only a few of us over here, and it stays pretty quiet,” he said.

While the city clearly has spent significant amounts of money in the past tearing down derelict homes around Carter’s house, many vacant and burned-out structures remain.

He was surprised to hear the neighborhood would have to wait for an unspecified time for more city activity.

“There’s a lot of empty houses and a lot of burned-out houses here, up Chapel here, Burgess, Bentler. In a three-block area, I guarantee you you’ll see about 10 houses that have been burned down and need to be torn down.”

Carter sees a conspiracy, but he admits he has no proof.

“What I believe is going on is that someone – this is just my belief, but I’m almost sure that it’s happening – someone purchased a certain amount of property that has some pull in the city, and they’re going to develop that property, so they need to tear down houses to get people out to redevelop it, to put in new houses,” he said.

Yet despite the abundant vacant land within sight of Carter’s house, there appears to be no evidence developers are rushing in to build.

Demolitions bittersweet

Likewise, in the Osborn neighborhood on the city’s northeast side, Rodney Frazier is left wondering. He’s glad the city has picked his neighborhood for aggressive demolition, knocking down two homes on his block and roughly 50 in his neighborhood in the last year.

But he bemoans the loss of neighbors and wishes the abandonment didn’t lead to grass-covered gaps between the homes on Teppert. As he talked, Detroit police were conducting a raid on a home just a few doors down and three women were detained on the porch as police scoured the house.

He wanted to buy some of the homes that the city owned but couldn’t beat out others. He figured he’d get a first shot, as an owner himself. Instead, others bought them, including one that’s already been torched. Frazier had owned two other homes but lost them to foreclosure, unable to secure good tenants who didn’t damage the property.

“I was trying to keep up the block,” he said. Still, though he has a good job and drives to Sterling Heights for work, he doesn’t intend to leave Detroit. What he hopes for is something concrete from the city, a strategy that he can see.

“They need to have some kind of plan,” he said.

For now, that plan includes knocking down as many crumbling homes as it can, an important first step in a city beset with blight.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Gray Carter in front of his Brightmoor home, with the rural-like landscape east of Outer Drive behind him. His street won’t see new demolition activity for some time. (photo by Bill McGraw)

Gray Carter in front of his Brightmoor home, with the rural-like landscape east of Outer Drive behind him. His street won’t see new demolition activity for some time. (photo by Bill McGraw) Gary Carter and Sherrod Hicks live just blocks apart in Brightmoor, but Hicks lives within an area targeted for massive demolitions. Carter can only wait for city to turn attention toward his neighborhood.

Gary Carter and Sherrod Hicks live just blocks apart in Brightmoor, but Hicks lives within an area targeted for massive demolitions. Carter can only wait for city to turn attention toward his neighborhood. Sherrod Hicks stands along W. Outer Drive, the dividing line between areas that are targeted for multiple demolitions and no immediate demolitions. Hicks is glad to see bulldozers level abandoned homes in his neighborhood. (photo by Bill McGraw)

Sherrod Hicks stands along W. Outer Drive, the dividing line between areas that are targeted for multiple demolitions and no immediate demolitions. Hicks is glad to see bulldozers level abandoned homes in his neighborhood. (photo by Bill McGraw) Detroit resident Rodney Frazier, a pressman who lives on Teppert Street, has three abandoned homes across from his own. (photo by Bill McGraw)

Detroit resident Rodney Frazier, a pressman who lives on Teppert Street, has three abandoned homes across from his own. (photo by Bill McGraw)